Berlin buries prisoners' tissue kept by Nazi-era doctor

- Published

The tissue slides were buried together in one small coffin

More than 300 tiny pieces of human tissue from prisoners executed by the Nazis have been buried in Berlin.

The samples were found in microscopic slides at a property that belonged to Hermann Stieve - an anatomy professor at the Charité university hospital.

Heirs of the doctor, who died in 1952, discovered the collection in 2016.

Researchers say Stieve systematically collaborated with the Nazis to receive the bodies of 184 people, mostly women, executed for political resistance.

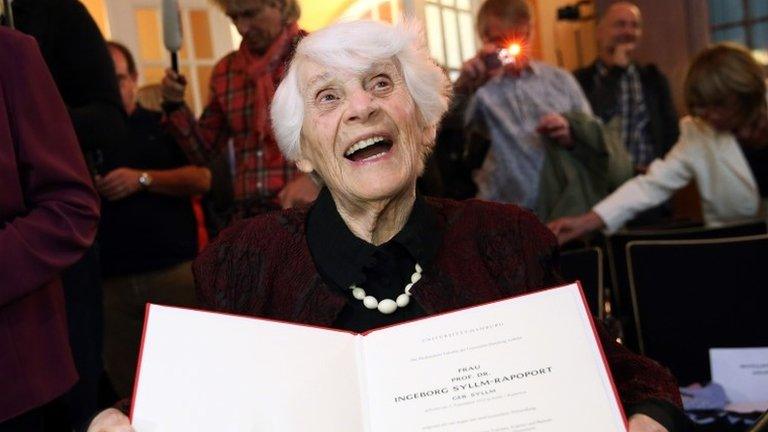

Some of the women whose bodies were used by Stieve (pic: GDW)

The tissue pieces - most less than a millimetre long - were discovered at Stieve's estate, stored in small black boxes, including some labelled with names.

Once found, they were handed to Berlin's Charité university hospital, who tasked staff at the German Resistance Memorial Center (GDW) , externalto research their history.

The burial ceremony on Monday took place at Berlin's Dorotheenstadt Cemetery. The grave is near an existing memorial to victims of the Nazis.

The samples were interred in one small coffin measuring 30cm x 30cm x 40cm (12ins x 12ins x 16ins), GDW director Johannes Tuchel told the BBC.

Some of the people dissected by Stieve were high-profile - including 13 women from the Red Orchestra anti-Nazi resistance group.

Bodies cremated

Research under Prof Tuchel shows that bodies were picked up by a driver and taken to Stieve, sometimes just minutes after they were killed at Berlin-Plötzensee prison.

He then dissected them for research,, external before discreetly cremating and interring their bodies anonymously.

Prof Tuchel told the BBC that Stieve's dissections took place in 1942-1943. He sent the bodies to Wilmersdorf for cremation and later sent the victims' ashes to Parkfriedhof Marzahn, a Berlin cemetery.

"He did not deal with concentration camp victims," Prof Tuchel said, adding that Stieve "did not work with Nazi doctors".

Almost 3,000 people were executed at Plötzensee by beheading or hanging while Hitler was in power.

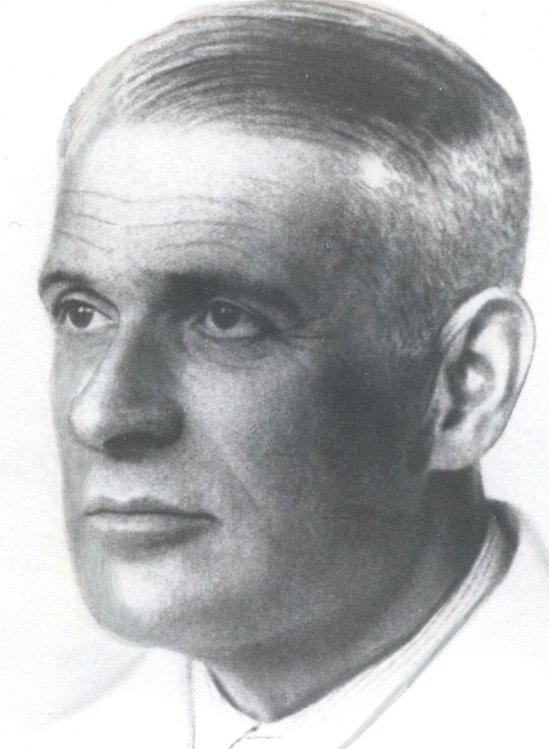

Hermann Stieve used the bodies of executed prisoners

"We have discovered that (Stieve) systematically aided the (Nazi) Reich justice ministry in obliterating the traces of these criminal acts," Prof Tuchel told German newspaper Bild.

Stieve served as the director of the Berlin Institute of Anatomy from 1935 until he died following a stroke in 1952.

Detailed records

The anatomist's use of the prisoners' corpses had been kept almost in plain sight, because he kept meticulous records of his work.

He had a particular interest in reproductive anatomy.

His work was some of the first research to suggest that stress - in the form of being sentenced to death - could disrupt a woman's menstrual cycle.

One of the Charité researchers, Andreas Winkelmann of Brandenburg Medical School, told the AFP news agency that burial of such small specimens was highly unusual.

"But this is a special story, because they came from people who were actively denied graves, so that their relatives would not know where they are buried," he added.

Dr Sabine Hildebrandt is a German-born anatomist who published a book about ethical transgressions and anatomical science in the Nazi period.

In 2013 she explained to the BBC that Stieve exploited their policies, including the increased use of the death penalty as a punishment.

Tens of thousands of political opponents were murdered by the Nazis

"Before 1933, he was able to source the bodies of executed men, but no women; Germany was not executing women," she said.

"Then, suddenly, during the Third Reich, women were being executed too."

Because he was not a member of the Nazi party, Stieve was not prosecuted after World War Two.

In a statement, Dr Karl Max Einhäupl, CEO of the Charité, said the burial was part of an effort by the hospital to confront its - and German medicine's - difficult relationship with Nazism.

"By burying the microscopic specimens at the Dorotheenstadt Cemetery, we want to help restore to the victims some of their dignity," he said.

- Published28 January 2015

- Published9 June 2015

- Published20 March 2018

- Published30 January 2019