Russia and Putin: Is president's popularity in decline?

- Published

The level of support for President Putin is now under intense debate in Russia

Within months of Russian President Vladimir Putin clinching his fourth term in office, Russia hosted the World Cup.

It was June 2018, and all eyes were on the country. The competition went off without a hitch - and fans and teams alike praised their Russian hosts for putting on such a smooth show.

But there was no honeymoon period for its leader.

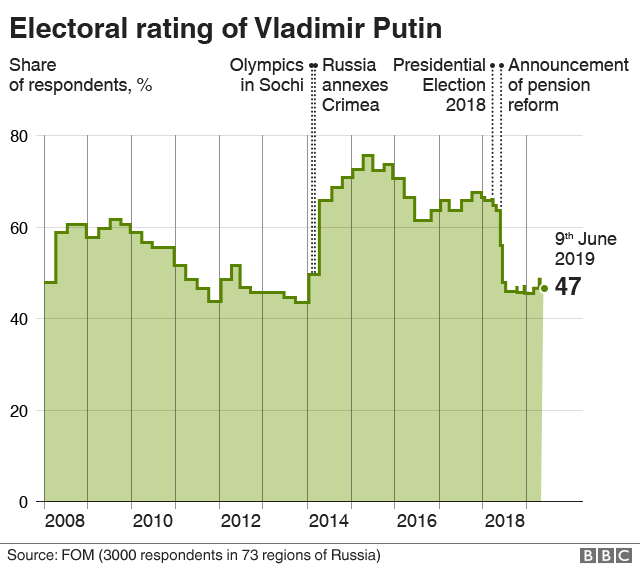

His approval rating, according to state-sponsored polling agency FOM, dropped from 64% on election day in March 2018 - the highest for any presidential candidate in modern Russian history - to 56% at the start of the World Cup.

By mid-summer, it was 49% - his poorest approval rating since he first became president in 2000.

Now, a year on from the World Cup, support for Russia's leader is again the subject of intense debate.

The ratings controversy reached its peak this month just before the St Petersburg International Economic Forum, a showcase event and one of Vladimir Putin's personal projects, which aims to lure foreign investors back to Russia.

A week before the forum began, national polling agency VTSIOM published a survey showing that public trust in the president had fallen to 31.7% – its lowest level since 2006.

The BBC's Steve Rosenberg reviews the Russian press on a poll into trust of President Putin

The timing was clearly awkward – and the Kremlin demanded an explanation.

But VTSIOM would appear to have got the message – because within days, it announced it had changed the form of its questions.

Rather than asking Russians which politicians they trusted, the pollsters asked specifically whether or not they trusted Mr Putin.

As a result, his trust ratings appeared to jump from a little over 30% to 72.3% in less than a week.

Pro-Kremlin governor Oleg Kozhemyako, in the Primorye region of Russia's Far East, believes there has to be a simple explanation for the drastic rise in Putin's popularity.

"The low ratings must have been the result of a miscount," he told the BBC.

But the former mayor of Yekaterinburg, Yevgeny Roizman, who defeated the government's candidate in elections in 2013, believes the pollsters are artificially overstating the results.

"I am sure the real rating is much lower," Mr Roizman told BBC Russian.

What led to the fall in popularity?

The reason for the initial slump in ratings, according to the pollsters, was a controversial move in June 2018 to raise the pension age in Russia - from 55 to 60 for women and from 60 to 65 for men.

As the average life expectancy for a Russian man stands at 66, that offered the prospect of working to within a year of your death.

"Enough" reads a placard held by a protester in Ivanovo north-east of Moscow in July 2018

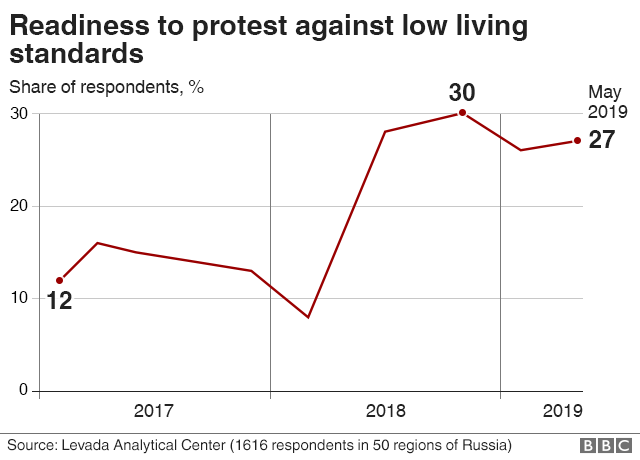

Across the country, people of all ages – many of whom had never protested before – came out on to the streets to show their anger.

"I would never have voted for Putin if I'd known he was going to put up the age at which we receive our pensions," Marina, 57, a retired teacher from Krasnodar, told the BBC.

And in the following months, support continued to fall.

In September 2018, the Kremlin fiercely criticised gubernatorial elections in which three opposition candidates triumphed over pro-government hopefuls. It was an unprecedented result.

At the same time, nationwide demonstrations began against overflowing rubbish sites and a growing problem with landfill.

Then, last month, Mr Putin was forced to step in personally to bring an end to clashes between police and protesters over the construction of a church in one of the few green spaces in the city of Yekaterinburg.

Many protest artists are turning to social media to amplify their performances and reach new audiences

What irks Russians more than any of this is the decline in living standards.

According to the Levada Centre, an independent polling agency, people are concerned most of all by poverty, price rises, corruption, the gap between rich and poor and the continuing economic crisis.

Is the Kremlin worried?

On the face of it, the Kremlin has appeared unruffled by the president's declining popularity ratings, saying publicly there was no reason to panic.

But "Putin is the personification of all the power in Russia," according to Andrei Kolesnikov from Carnegie Moscow Centre.

"His personal rating reflects attitudes towards every government institution. If he loses support, every minister and official loses it, too."

"Kremlin officials have to insist that Putin's ratings don't bother them. Officially, they have to appear confident. But there's no question they have been watching the figures closely and are starting to feel nervous."

- Published3 February 2018

- Published17 March 2024

- Published14 March 2018

- Published12 March 2018