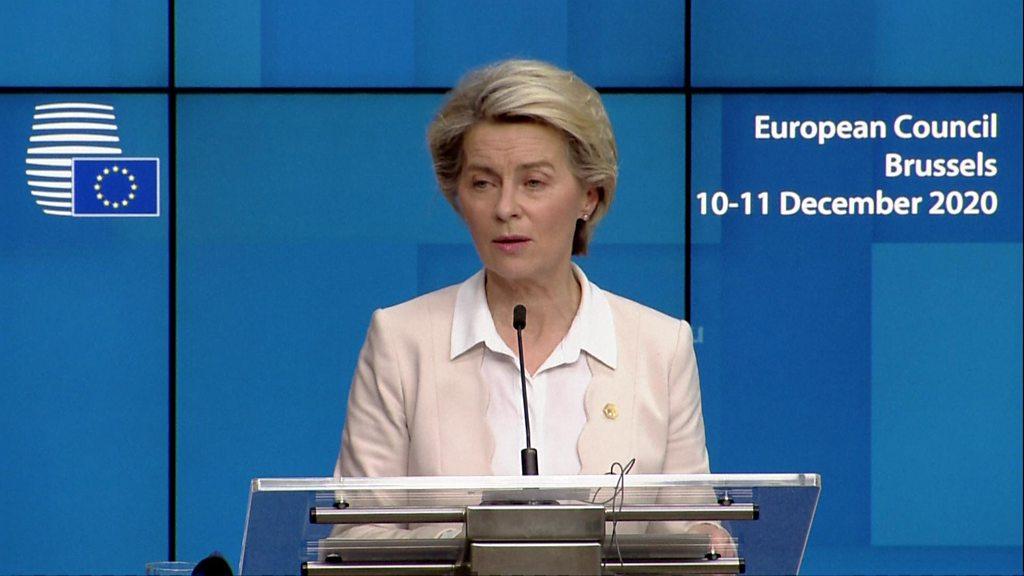

Ursula von der Leyen: First woman to lead the EU

- Published

Ursula von der Leyen is a close ally of German Chancellor Angela Merkel

"For me, it's like coming home," said Ursula von der Leyen of her new job as president of the European Commission. Brussels born and bred, she is a former German defence minister, a long-term ally of Chancellor Angela Merkel, and the first woman to head the EU's powerful executive.

Mrs von der Leyen replaced Jean-Claude Juncker in the EU's top job on 1 December 2019 and part of her role is overseeing Brexit.

She has warned that ending 2020 without a trade deal with the UK would be "a cliff-edge situation", which "would clearly harm our interests", but would "impact more the UK than us".

"We are not ready to put into question the integrity of our Single Market - the main safeguard for European prosperity and wealth," she said.

EC President Ursula von der Leyen says Brexit will be "new beginnings for old friends"

She was not the first choice for the EU's most powerful job. She was not especially popular in her previous role among Germany's armed forces, and only emerged from the shadows as a candidate for Commission chief when initial compromise deals collapsed.

Eventually she was nominated by EU member states and then backed by the European Parliament, after a political stalemate over other contenders.

Her responsibilities include proposing new EU laws, enforcing the bloc's rules and handling trade deals.

Mrs von der Leyen has a reputation as a workaholic. Her decision to sleep in a bedsit adjoining her office at the Commission HQ, external rather than making a home in Brussels has also raised eyebrows.

Where does she stand on the big issues?

She set out her values both before and after assuming office:

Gender balance: Mrs von der Leyen, the first woman to serve as president, selected a team of 27 EU commissioners including 12 women at the top table.

Climate change: Within days of taking office she promised a "European Green Deal", external, to set Europe on a path to "climate neutrality" - that is, net-zero greenhouse gas emissions - by 2050, and creating a transition fund for countries still dependent on fossil fuels.

Ursula von der Leyen said she wanted Europe to be the first "climate-neutral" continent

Brexit: She warned the UK that the timetable to conclude an agreement - by the end of 2020 - was "extremely challenging", adding that whatever happened, the EU would remain united and continue to benefit from its single market and customs union.

Migration: She said she was committed to reforming the EU's asylum system, which member states have been struggling with for years, with a reinforced border guard. She spoke in favour of enlarging the eurozone and the EU's open-border Schengen area, and said the bloc should be ready to take in Western Balkan countries.

Defence: While backing Nato as the "cornerstone of our collective defence", she said the EU should invest in joint defence capacities that would complement those of the Western alliance. The EU should "become more assertive" towards the United States, she said.

What's her background?

Ursula von der Leyen was born in Brussels in 1958, and attended the European School - a multilingual elite school for the children of diplomats and EU bureaucrats.

A few years later, in the 1970s, Boris Johnson attended the European School, as his father was an official in the then European Economic Community (EEC).

Mrs von der Leyen's father Ernst Albrecht was a senior Commission official in Brussels in the 1950s, before entering German domestic politics - he was in the conservative Christian Democrats (CDU), today led by Chancellor Merkel. He became premier of the state of Lower Saxony in 1976.

He came from a privileged family of merchants. Her mother had a university doctorate and academic success was much encouraged, journalist Ben Judah has written, external in a study of Ursula von der Leyen.

With her parents and five siblings she moved to Germany aged 13. Family life was comfortable, on a farm near Hanover - Ursula came to love horse-riding - and the children performed in home plays and concerts, sometimes in front of politicians.

Ursula (L) with her parents Ernst Albrecht and Heidi-Adele in April 1978

Later she studied economics at London's LSE and medicine in Hanover before going into politics.

In London she went by the name Rose Ladson - at the time German politicians were being targeted by Red Army Faction leftist militants. Her family nickname had been Röschen - "little rose". She enjoyed partying and rock concerts.

She told Germany's Die Zeit daily that "London was for me then the epitome of modernity: freedom, the joy of life, trying everything".

Later in Germany she met Heiko von der Leyen, a doctor, at medical school and they got married in 1986.

Fluent in English and French, she has been a member of the CDU since 2005.

She said her father always told his children that when countries traded, they built friendships and did not shoot each other.

Now 62, Mrs von der Leyen is the mother of seven children, highly unusual in a country where the average birth rate is 1.59 children per woman.

Ursula von der Leyen with her children in October 2003

She is seen as a staunch integrationist, backing closer military co-operation in the EU and highlighting the "potential Europe has to unify and to promote peace, external".

Her appointment as German defence minister in 2013 was unexpected and followed three months of coalition talks between the CDU and the centre-left Social Democrats (SPD).

As defence minister in the EU's most industrialised and populous country, she argued for Germany to boost its military involvement in Nato.

However, her tenure in the defence post was not without incident.

What was her record as defence minister?

In recent years, a litany of stories have exposed inadequacies in Germany's armed forces, from inoperable submarines and aircraft to shortages of personnel.

A report published in 2018 highlighted the shortfalls, saying they were "dramatically" hindering Germany's readiness for combat. It said that no submarines or large transport planes were available for deployment at the end of 2017.

While her appointment was initially seen as a fresh start for a German ministry beset by problems, Mrs von der Leyen was questioned as part of an investigation into spending irregularities.

Her defence department was accused of awarding questionable private contracts to consultants that were said to be worth millions of euros.

She later admitted that a number of errors were made in allocating contracts and that new measures were being implemented to prevent it happening again.

That period of her career has not gone away. In December 2019, German MPs accused the defence ministry of deliberately deleting key data from her office mobile phone in an attempt to obstruct their investigation.

- Published11 December 2020

- Published2 July 2019

- Published27 May 2019