Germany's far-right AfD: Victim or victor?

- Published

AfD poster: In 1989 "We are the people!" was chanted by anti-communist protesters

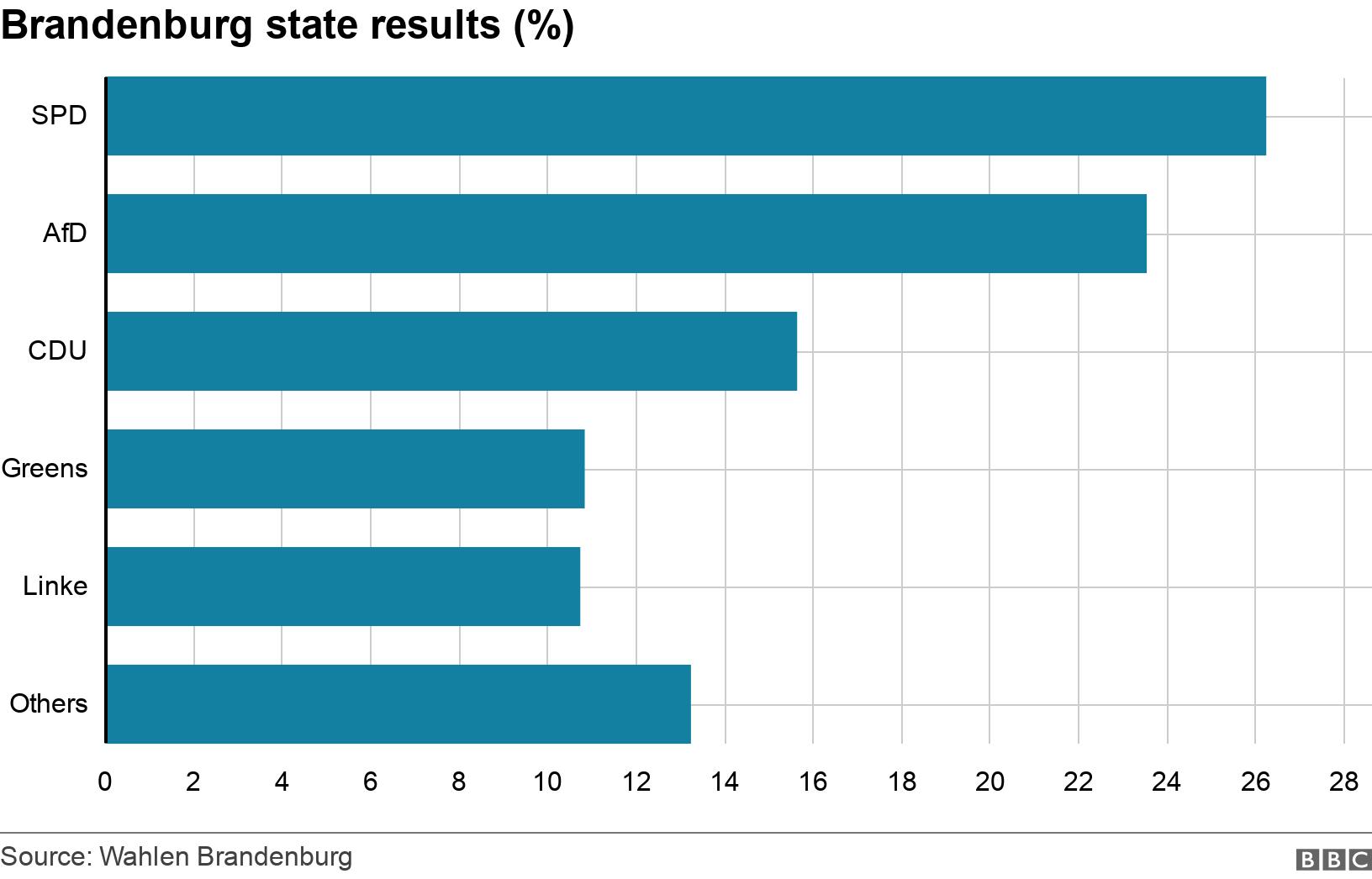

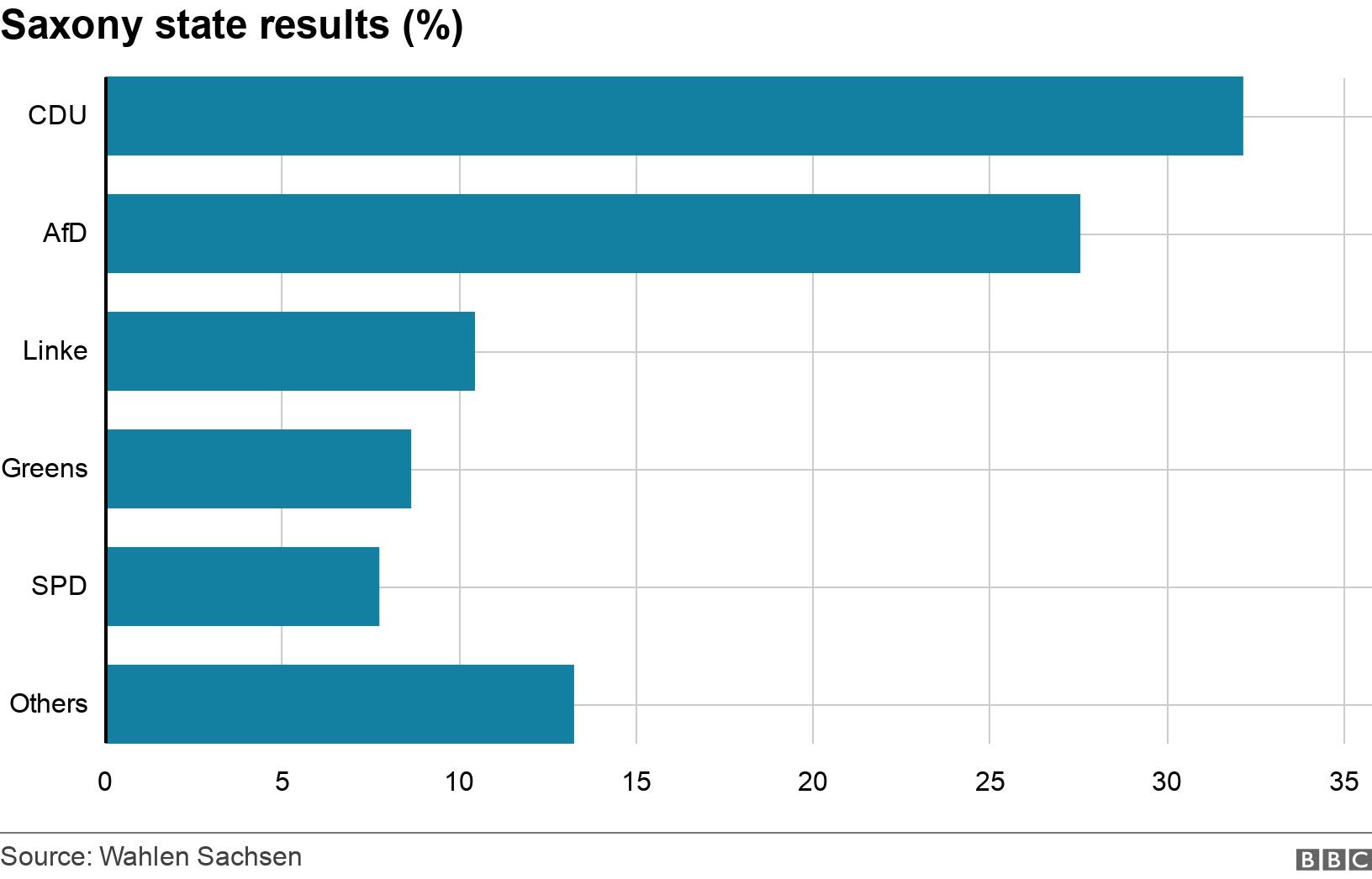

Germany's two main parties are breathing a sigh of relief. The far-right populist Alternative for Germany (AfD) has been fought off in two big eastern regions - for now.

Chancellor Angela Merkel's conservative Christian Democrat Party (CDU) looks set to hang on to power in Saxony, and the centre-left Social Democrats (SPD) should be able to stay in government in Brandenburg.

Both parties saw their share of the vote drop, compared with the last state elections here in 2014, and it was an all-time low for the SPD. These were not good results for them.

But the losses were not as big as some had feared.

A lot has happened since 2014 - including the refugee crisis and the AfD - so leaders can justifiably say things could have been worse.

Crucially, both the CDU and the SPD won the most votes in their respective states, so will now start coalition talks to lead new state governments.

Eastern grievances

The AfD sees itself as the winner. The party saw huge gains compared with the 2014 elections, so it had reason to celebrate.

The AfD ran a politically savvy campaign. It tapped into historical grievances in former communist eastern Germany, by co-opting phrases from the dissident movement that brought down the Berlin Wall 30 years ago.

The AfD posters demanded a "Wende 2.0", using the German word for the peaceful revolution that brought down East German communism, and the AfD leaders compared Mrs Merkel's government to the Stasi secret police.

The AfD's campaign has sparked a national debate about disaffection in the "East". In many ways German reunification has been a success. Unemployment is low and the immaculately renovated cities in both these states are booming.

But there are still economic disparities. Wages and pensions are lower here than in western Germany, many young people have left to find work, and rural areas often lack basic amenities.

There is also a feeling that the "West" has taken over, and that eastern Germany is ignored. The most influential voices in society tend to be western Germans.

When migrants started arriving in 2015 some of that resentment tipped into anger - the perception being, fairly or not, that locals hadn't been consulted, and that refugees were being treated better than local people.

The 1989 chant of east German dissidents - "We are the people!" - is used by the AfD at anti-immigration rallies.

The party's leaders, ironically themselves mostly Westerners, have successfully turned these grievances into votes.

The AfD adopted the slogan "dissident" - a nostalgic throwback to 1989

But the AfD won't enter government in either state. The party is accused of xenophobia, and some members have links to neo-Nazi groups. So no other party will work with them in a coalition.

Anti-establishment image

The AfD hoped to win the most votes in at least one state. That would have been a game-changer. It would have made the AfD the most powerful party in a German state parliament for the first time, and emboldened those right-wing rebels in Mrs Merkel's CDU/CSU bloc who would like to work with the AfD in future coalitions.

For now the AfD is exactly where it was before - stuck in opposition. This may be a surge compared with 2014. But the numbers are consistent with results in the May EU elections and the last German federal election. Some wonder if the party has reached its limit.

But the AfD is ready to fight. Party leaders are already spreading the message that they are being unfairly shut out of government by the "establishment".

And because the AfD and the Greens have both taken votes away from the two main parties, it will be harder to form a stable coalition. At least three parties, all with very different ideologies, will be needed. Drawn-out coalition talks and internal government rows will be used by the AfD to show that the "system" is not working.

This all plays into the victimhood narrative that the AfD will continue to hammer home: that the "establishment" - the parties supported by around 75% of the population here - does not represent the true will of the people.

For the AfD, its status as victim is the key to future success.

- Published2 September 2019