Earthquakes: Donegal school has its ear to the ground

- Published

"It connects you to the outside world"

An earthquake in the Dodecanese Islands is a long way from Stranorlar in County Donegal.

However, it has put a school there on top of the world.

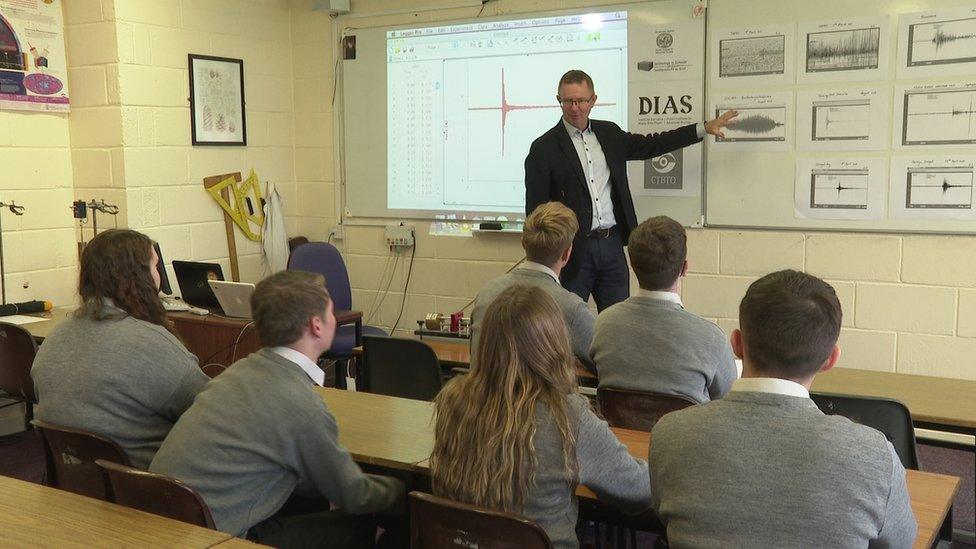

Physics teacher Brendan O'Donoghue was the driving force behind St Columba College joining the international Seismology in Schools network.

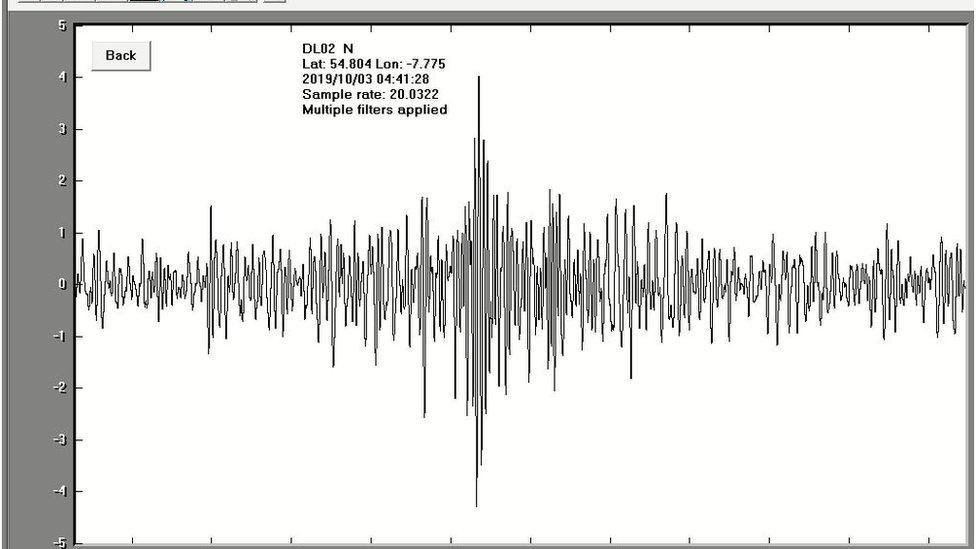

The Dodecanese event was the college's 1,000th recording, making it the highest-performing individual school out of 700 institutions worldwide.

"For the last nearly 10 years now, we've had a seismometer running 24/7 in the school and all during that time we've recorded earthquakes from all over the world," Mr O'Donoghue said.

"We collect data from local events here in Donegal because we get our own locally generated earthquakes and we record catastrophic events from the other side of the world.

Physics teacher Brendan O'Donoghue was the driving force behind St Columba College joining the international Seismology in Schools network

"And we also record other events - the North Korean nuclear test two years ago or the eruption of a volcano in Iceland.

"Anything that makes the earth shake, we can record it here if it has a high enough intensity."

As well as recording earthquakes, the school contributes to international monitoring bodies for things like nuclear tests.

County Donegal itself is a hotbed of seismic activity, thanks to its geology.

The Dodecanese earthquake was St Columba College's 1,000th recording

"Donegal would have been close to the suture point of ancient continents hundreds of millions of years ago, so those ancient faults are there," Mr O'Donoghue said.

"And what's happening in Donegal and all across the north Ulster coast is activity since the last Ice Age 10,000 years ago.

"The north of the country would have been covered in an ice sheet, up to a kilometre thick in places and the weight of that ice just pushes the crust of the earth down into the mantle which is fluid.

"Anything that makes the earth shake" is recorded at the school

"Then the ice melted away and ever since, the ground has been coming back up in what's called isostatic adjustment."

That process led to two earthquakes in Donegal in April this year, much to the delight of head girl and earthquake enthusiast, Siobhan.

"I thought this was so exciting, because as I said I'm really into geography," she said.

"They were saying it was like an ice cap that used to be over the north of Ireland and then the ground's still coming up, so it's really interesting to see things that happened millions of years ago are still affecting the world in which we live."

She's not the only one.

Another pupil, Cael said: "The data we collect kind of connects you to events that might be happening on the other side of the world, as well as the smaller earthquakes we find in Donegal too."

It's been useful to Pete in his studies as well.

Mr O'Donoghue said it gives pupils a sense of their place in the world and how connected people are

"It's really interesting that we can analyse the data we've collected ourselves as opposed to finding it online or reading it out of a textbook," he said.

"We can collect it ourselves, we can really learn from that in a more real way."

That means a lot to their teacher, Mr O'Donoghue.

"It shows that they are making that connection with people who are suffering due to these catastrophes, so it gives them a sense of their place in the world and how connected we all are," he said.

Ironically, although the project is all about education, the equipment works best when there's nobody at the school.

"During the day here, from 8am to 5pm the data is nearly useless because of the activity in the school building - doors opening and closing and people walking down the corridor," Mr O'Donoghue said.

"All those things cause seismic waves on a small local scale and they all register on the seismometer.

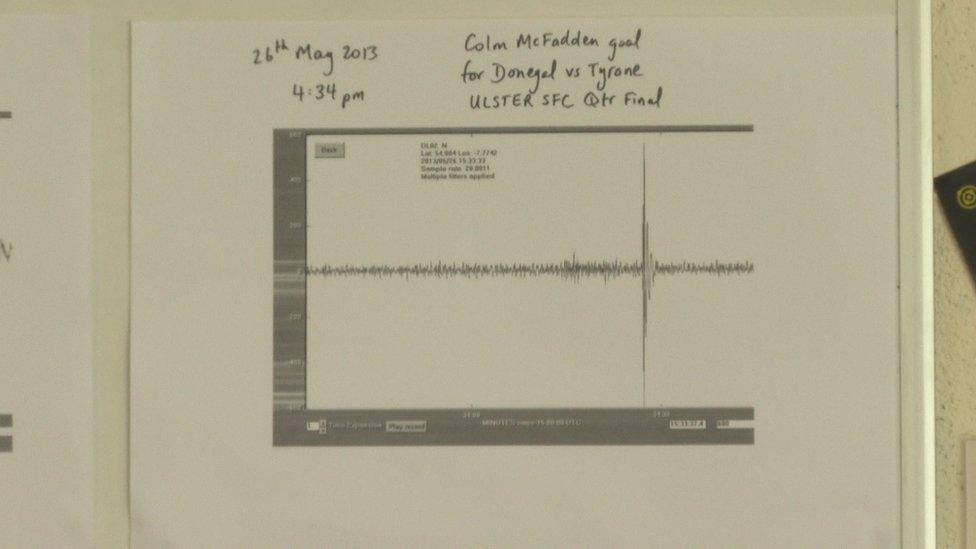

A goal scored in McCool Park during a senior football championship match between Donegal and Tyrone was picked up

"So when the caretaker opens the building in the morning and locks up at night, sometimes we get the trace showing those moments of the door closing.

"And we can see it then settling down and becoming quiet, so most of our data is collected at night."

Among the 1,000 recordings under their belt, they've picked events as powerful as 8.9 on the Richter scale.

Earthquakes closer to home tend to be a lot less powerful, but no less meaningful.

"The most significant one probably here locally was the one that was a goal scored here in McCool Park during a senior football championship match between Donegal and Tyrone," Mr O'Donoghue said.

"We picked up the vibration at the ground at the exact moment the ball went into the net - so thank you to Colm McFadden for that one."