Why Poles want more of this man's populist message

- Published

After his election win, Jaroslaw Kaczynski said: "Poland must change more and... for the better"

Victory for Poland's governing Law and Justice party in parliamentary elections has turned out to be bitter sweet.

Despite winning 43.6% of the vote, the largest voter share since democracy was restored 30 years ago, the party had been hoping for an even higher result and it lost control of the less powerful upper house - the Senate.

But the victory showed that Law and Justice's socially conservative views and statist redistribution policy to help poorer Poles enjoys significant support.

Millions of Polish families are receiving benefits to help them make ends meet and now feel for the first time there is a party that cares about their dignity.

The result also shows that the party's controversial efforts to increase political control over the judiciary, which has led opponents and the European Union to accuse it of weakening Poland's democracy, were not decisive.

What can Poles expect next?

The party's leader, Jaroslaw Kaczynski, widely considered to be the most powerful politician in Poland, said during the campaign it was time to change the country's political, economic and cultural elites.

The 70-year old leader believes that communists were not purged from public life during Poland's peaceful transition from communism to a democratic market economy in 1989, and consequently post-communists still wield too much influence over how the country is run.

Mr Kaczynski: "Christianity is part of our national identity, the [Catholic] Church was and is the preacher and holder of the only commonly held system of values in Poland"

Early in its first term, the party politicised the civil service, cultural institutions and public media.

Public radio and television has always been partial to whichever party was in power, but Law and Justice has essentially turned it into a spokesperson for the governing camp.

The party says that's necessary to counteract the hostility towards it from much of the private media.

What problems lie in store?

Most problematic for Mr Kaczynski is the judiciary, which Law and Justice described in its populist rhetoric as a self-serving and corrupt elite that does not serve the needs of the people.

The party also made use of the popular view that the judiciary was inefficient and that trials dragged on too long.

During its first term, the governing camp introduced legislation to take political control, first of the Constitutional Court, then the National Council of the Judiciary - the body that nominates judges in Poland - and then the Supreme Court.

Law and Justice say the changes fall within the European mainstream and the judiciaries in Germany and Spain are in many ways more politicised.

But the European Commission disagreed and launched - for the first time - an investigation against Poland over concerns it had seriously breached the rule of law and weakened democracy.

Unless you reform the judiciary... you can't break the post-communist networks and mafias

Since all EU member states must agree to impose sanctions against Poland under that investigation, an unlikely outcome, the procedure has not caused Warsaw to backtrack.

The European Commission launched legal action at the EU Court of Justice. When the Luxembourg court ruled that Poland had broken EU law in the Supreme Court case, the government conformed to the ruling.

There are several more cases pending at the court but, during the campaign, Mr Kaczynski vowed to continue the reform.

Jacek Karnowski, a journalist for pro-Law and Justice weekly wSieci, said it was now a question of prestige for Mr Kaczynski to complete the reforms.

"Unless you reform the judiciary, you can't have a prosperous free market country and you can't break the post-communist networks and mafias," he told the BBC.

"[Mr Kaczynski] suspects judges of being politically motivated, of wanting to topple the government. He does not want to dominate the judiciary 100% because he knows that's not possible, but he wants to make it less on the side of the opposition," he said.

A threat to democracy?

Konstanty Gebert, a columnist for the liberal Gazeta Wyborcza daily, which is anti-Law and Justice, says the party's policies have weakened democracy, although it does not wish to destroy it.

"They essentially believe that having a parliamentary majority gives them the right to do whatever they please and that the peoples' will is more important than the law," he told the BBC.

"It's a mistake to believe that their goal is to destroy democratic institutions. They are not ideologically undemocratic. They wouldn't support anything the people wouldn't support. Their version of democracy is majoritarian democracy," he said.

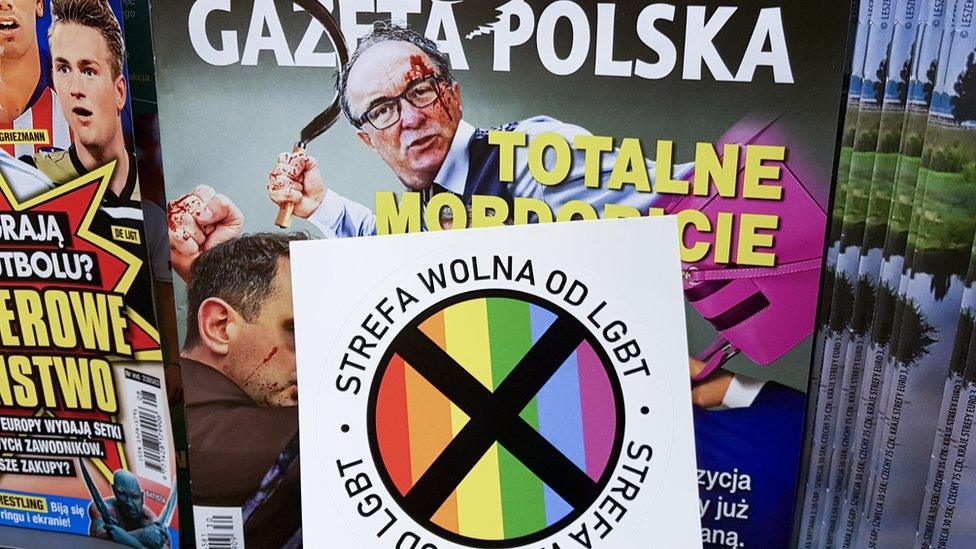

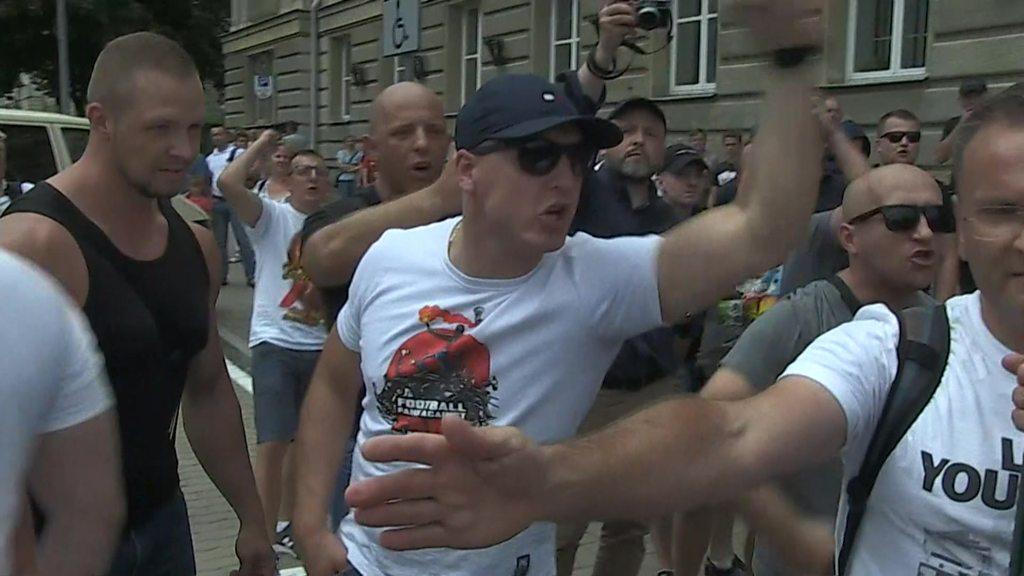

Poland has seen an increasing number of equality marches in 2019, including this one in Torun

Minorities, like LGBT people in Poland, will likely continue to be stigmatised as a threat to traditional families and Catholic Polish society as they were by Law and Justice during the election campaign.

What challenges does it face?

During Law and Justice's first term, there was talk of introducing legislation to restrict foreign-owned companies' share of the private media market.

But the party may pull back from that, because it did not do as well as it hoped, Mr Karnowski argues.

The re-entry of the left after a four-year absence and the arrival of the far-right Confederation to the Polish parliament pose challenges to Law and Justice's dominance this term, says Konstanty Gebert.

"Law and Justice are now the establishment. They will be outdone on the one side by the far right who will out-patriot them every time and on the other by the left who will come up with more creative redistributive policies," he said.

- Published14 October 2019

- Published8 October 2019

- Published25 July 2019

- Published22 July 2019

- Published28 May 2018