Why Brexit is pushing the UK towards an early general election

- Published

The UK parliament has voted in favour of an early general election, with a majority of MPs agreeing the vote should take place on 12 December.

Tuesday's motion - Prime Minister Boris Johnson's fourth attempt to secure a general election since he took office in July - will still need the approval of the House of Lords (the second chamber of the UK Parliament).

It is almost certain to pass and, if it does, it will be the country's third general election in less than five years - and the UK's first December election for nearly 100 years.

Mr Johnson said the move would help "get Brexit done", allowing Britain to move forward with its withdrawal from the European Union (EU).

So what just happened?

The Conservative leader got his pre-Christmas wish, with 438 MPs supporting (and 20 opposing) an early election.

The prime minister has been struggling to push his Brexit deal - negotiated with the EU - through parliament without a Conservative majority. He said an election was needed to end the "paralysis".

Ahead of Tuesday's vote, the leader of the opposition Labour Party, Jeremy Corbyn, said he would back a December election after the EU confirmed a Brexit extension up until 31 January 2020.

"So for the next three months, our condition of taking no-deal off the table has now been met," he said.

But Labour MPs were said to be split over their support for an election because of concerns over their party's position in the polls.

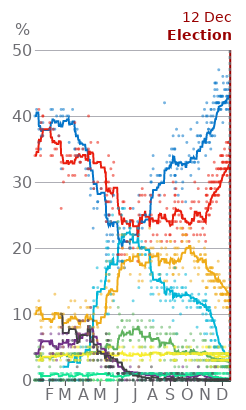

The BBC's own poll tracker, which measures how people say they are going to vote at the next general election, puts the Conservatives ahead of Labour by more than 10 percentage points.

Tuesday's motion was almost abandoned when the government threatened to pull the bill after opposition parties proposed allowing 16 and 17-year-olds and EU nationals with settled status the right to vote. The voting age is 18 or over.

What happens next?

A good question.

Peers in the House of Lords are due to consider the motion on Wednesday. Assuming it passes, Parliament will be dissolved next week with the election taking place on 12 December.

What happens next on Brexit would depend on the outcome of that election.

So an election could sort out Brexit?

Not necessarily.

To do so, an election needs to produce a majority for someone.

The Brexit deal agreed between Mr Johnson and the EU is currently in limbo after MPs voted against the three-day timetable to pass it through the Commons last week.

While an election could restore the Conservative Party's majority and give the prime minister more leverage in Parliament, an early election also carries risks for Mr Johnson and the Tories.

Leaving the EU by 31 October "do or die" was a key campaign promise in Mr Johnson's bid to become prime minister but he has since accepted an offer from EU leaders to extend Brexit until 31 January 2020.

As a result, voters could choose to punish him at the ballot box for failing to fulfil his campaign pledge.

This is where the main parties stand on Brexit:

Conservatives: A working majority would give them the numbers to push their deal through before the January deadline - or exit the EU without a deal

Labour: Mr Corbyn wants to try to renegotiate the Brexit withdrawal agreement in Brussels before a second referendum

Lib Dems: The party hopes to cancel Brexit by revoking Article 50 - part of a legal agreement triggered by former Prime Minister Theresa May

Scottish National Party: The pro-Remain party wants a second referendum

If a general election results in another hung parliament, it would arguably have achieved nothing.

A general election is supposed to take place every five years in the UK. The last election was in June 2017.

Is another referendum likely?

A new vote on Britain's EU membership could also break the stalemate over Brexit.

But organising another public vote would take a minimum of 22 weeks, according to experts at the Constitution Unit at University College London (UCL).

This would consist of at least 12 weeks to pass the legislation required to hold a referendum, plus a further 10 weeks to organise the campaign and hold the vote itself.

Also - and this is a recurring theme here - a government cannot just decide to hold a referendum. Instead, a majority of MPs and Members of the House of Lords would need to agree and vote through the rules of another public vote.

What about the Brexit extension?

EU Council President Donald Tusk said the latest extension was flexible and that the UK could leave before the agreed 31 January 2020 deadline if a withdrawal agreement is approved by the British parliament.

The extension text cites 1 December and 1 January as possible "early out" dates.

But Mr Tusk has also warned the UK not to waste the opportunity.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Is no-deal still possible?

Yes.

While Mr Johnson has formally accepted the EU's offer of a Brexit extension until 31 January 2020, it does not mean that a no-deal Brexit is off the table. Rather, it pushes the possibility further into the future.

No-deal Brexit: How might it affect the EU?

Mr Johnson is likely to continue to try to push his deal through Parliament and if his election gamble pays off, he may succeed. If, however, his efforts fail before the deadline for Britain's exit is reached, the UK could leave without a deal.

- Published30 October 2019

- Published29 October 2019

- Published28 October 2019

- Published28 October 2019

- Published13 July 2020

- Published28 October 2019

- Published28 October 2019

- Published27 October 2019