Venice floods: Climate change behind highest tide in 50 years, says mayor

- Published

Parts of Venice have been left under water by record flooding

Severe flooding in Venice that has left much of the Italian city under water is a direct result of climate change, the mayor says.

The highest water levels in the region in more than 50 years would leave "a permanent mark", Venice Mayor Luigi Brugnaro tweeted.

"Now the government must listen," he added. "These are the effects of climate change... the costs will be high."

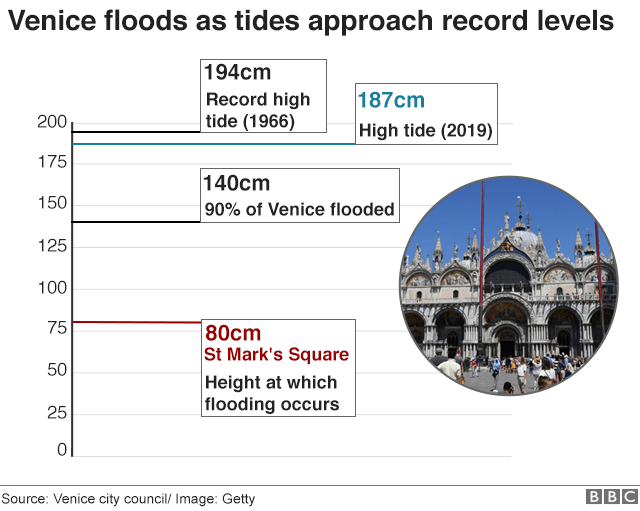

The waters in Venice peaked at 1.87m (6ft), according to the tide monitoring centre. Only once since official records began in 1923 has the tide been higher, reaching 1.94m in 1966.

Images showed popular sites left completely flooded and people wading through the streets as Venice was hit by a storm.

St Mark's Square - one of the lowest parts of the city - was one of the worst hit areas.

St Mark's Basilica was flooded for the sixth time in 1,200 years, according to church records. Pierpaolo Campostrini, a member of St Mark's council, said four of those floods had now occurred within the past 20 years.

The mayor said the famous landmark had suffered "grave damage". The crypt was completely flooded and there are fears of structural damage to the basilica's columns.

The city of Venice is made up of more than 100 islands inside a lagoon off the north-east coast of Italy.

Two people died on the island of Pellestrina, a thin strip of land that separates the lagoon from the Adriatic Sea. A man was electrocuted as he tried to start a pump in his home, and a second person was found dead elsewhere.

Mr Brugnaro said the damage was "huge" and that he would declare a state of disaster, warning that a project to help prevent the Venetian lagoon suffering devastating floods "must be finished soon".

"The situation is dramatic. We ask the government to help us," he said on Twitter, adding that schools would remain closed until the water level subsides.

He also urged local businesses to share photos and video footage of the devastation, which he said would be useful when requesting financial help from the government.

People throughout the city waded through the flood waters.

A number of businesses were affected. Chairs and tables were seen floating outside cafes and restaurants.

In shops, workers tried to move their stock away from the water to prevent any further damage.

One shopkeeper, who was not named, told Italy's public broadcaster Rai: "The city is on its knees."

Three waterbuses sank, but tourists continued their sightseeing as best they could.

One French couple told AFP news agency that they had "effectively swum" after some of the wooden platforms placed around the city in areas prone to flooding overturned.

On Wednesday morning, a number of boats were seen stranded.

A project to protect the city from flooding has been under way since 2003 but has been hit by soaring costs, scandals and delays.

The so-called Mose project - a series of large barriers or floodgates that would be raised from the seabed to shut off the lagoon in the event of rising sea levels and winter storms - was successfully tested for the first time in 2013.

The project has already cost billions of euros in investment. According to Italy's infrastructure ministry, the flood barriers will be handed over to the Venice city council at the end of 2021 following the "final phase" of testing.

Italy was hit by heavy rainfall on Tuesday with further bad weather forecast in the coming days. Venice suffers flooding on a yearly basis.

Is climate change behind Venice flooding?

By BBC meteorologist Nikki Berry

The recent flooding in Venice was caused by a combination of high spring tides and a meteorological storm surge driven by strong sirocco winds blowing north-eastwards across the Adriatic Sea. When these two events coincide, we get what is known as Acqua Alta (high water).

This latest Acqua Alta occurrence in Venice is the second highest tide in recorded history. However, if we look at the top 10 tides, five have occurred in the past 20 years and the most recent was only last year.

While we should try to avoid attributing a single event to climate change, the increased frequency of these exceptional tides is obviously a big concern. In our changing climate, sea levels are rising and a city such as Venice, which is also sinking, is particularly susceptible to such changes.

The weather patterns that have caused the Adriatic storm surge have been driven by a strong meridional (waving) jet stream across the northern hemisphere and this has fed a conveyor belt of low pressure systems into the central Mediterranean.

One of the possible effects of a changing climate is that the jet stream will be more frequently meridional and blocked weather patterns such as these will also become more frequent. If this happens, there is a greater likelihood that these events will combine with astronomical spring tides and hence increase the chance of flooding in Venice.

Furthermore, the meridional jet stream can be linked back to stronger typhoons in the north-west Pacific resulting in more frequent cold outbreaks in North America and an unsettled Mediterranean is another one of the downstream effects.

All images subject to copyright.

- Published13 November 2019

- Published31 December 2018

- Published30 October 2018