Malta's 'golden passports': Why do the super-rich want them?

- Published

Maltese Prime Minister Joseph Muscat has announced his resignation

A European Union mission is visiting Malta to "investigate the rule of law", as the fallout continues from the investigation into the killing of journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia.

The murder of Ms Caruana Galizia in 2017 has rocked the country's political establishment, and highlighted wider concerns about alleged corruption and a weak judicial system.

There is growing scrutiny of its so-called "golden passports" scheme, which has been described by an EU Parliament delegation as risking "importing criminals and money laundering into the whole EU", external.

If you bring €900,000, you can buy a Maltese passport and then you become an EU citizen."

The selling of citizenship has become a big global market for wealthy individuals looking for low taxes, elite education or for political reasons.

The European Commission says it is closely monitoring citizenship for sale programmes in the EU

But how much does it cost in Malta, and what do we know about those buying passports?

How do you buy Maltese citizenship?

The government introduced the scheme in 2014 to attract wealthy individuals and investment. To get a passport, applicants must contribute:

€650,000 (£554,000) to a national development fund

€150,000 into Maltese stocks or shares

Buy a property worth at least €350,000 (or rent one for €16,000 per year)

This comes to €1,150,000, so that's actually more than the €900,000 cost given by Dutch MEP Sophie in't Veld.

Applicants must also have held resident status for more than 12 months, although they don't have to have physically lived there.

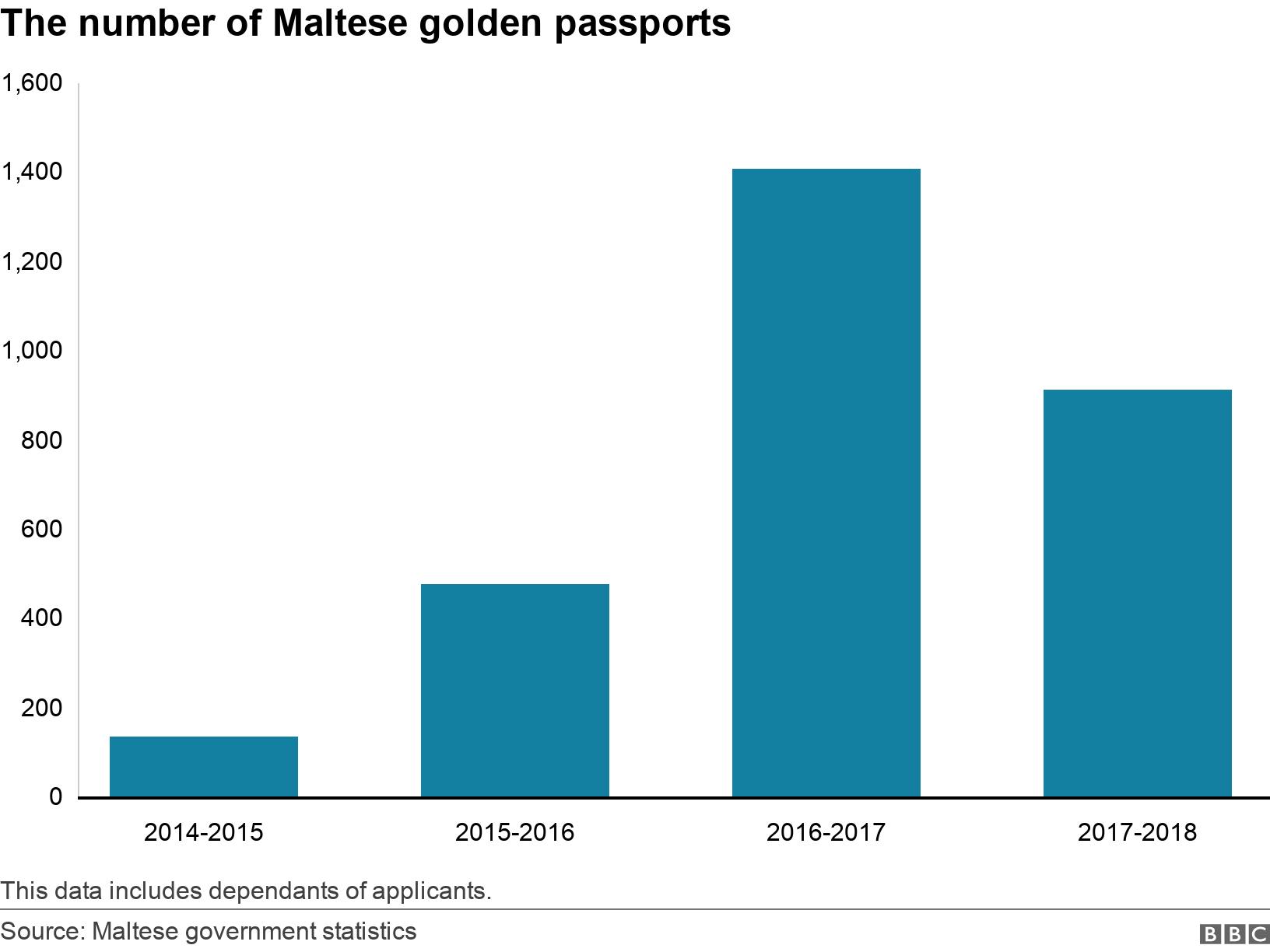

There've been 833 investors and 2,109 family members who have obtained Maltese citizenship since the scheme started.

A Maltese passport allows the holder visa-free travel to other European countries, as Malta is part of the Schengen agreement.

Between mid-2017 and mid-2018, the scheme raised €162,375,000 which equates to 1.38% of Malta's GDP in that period, although in 2018 there was a drop in the purchase of passports.

There's a clear incentive for small countries like Malta to have schemes like this to attract significant amounts of investment.

"Many microstates have become dependent on the income generated through such programmes," says Luuk van der Baaren, a migration researcher at the European University Institute in Florence.

Who is buying Maltese passports?

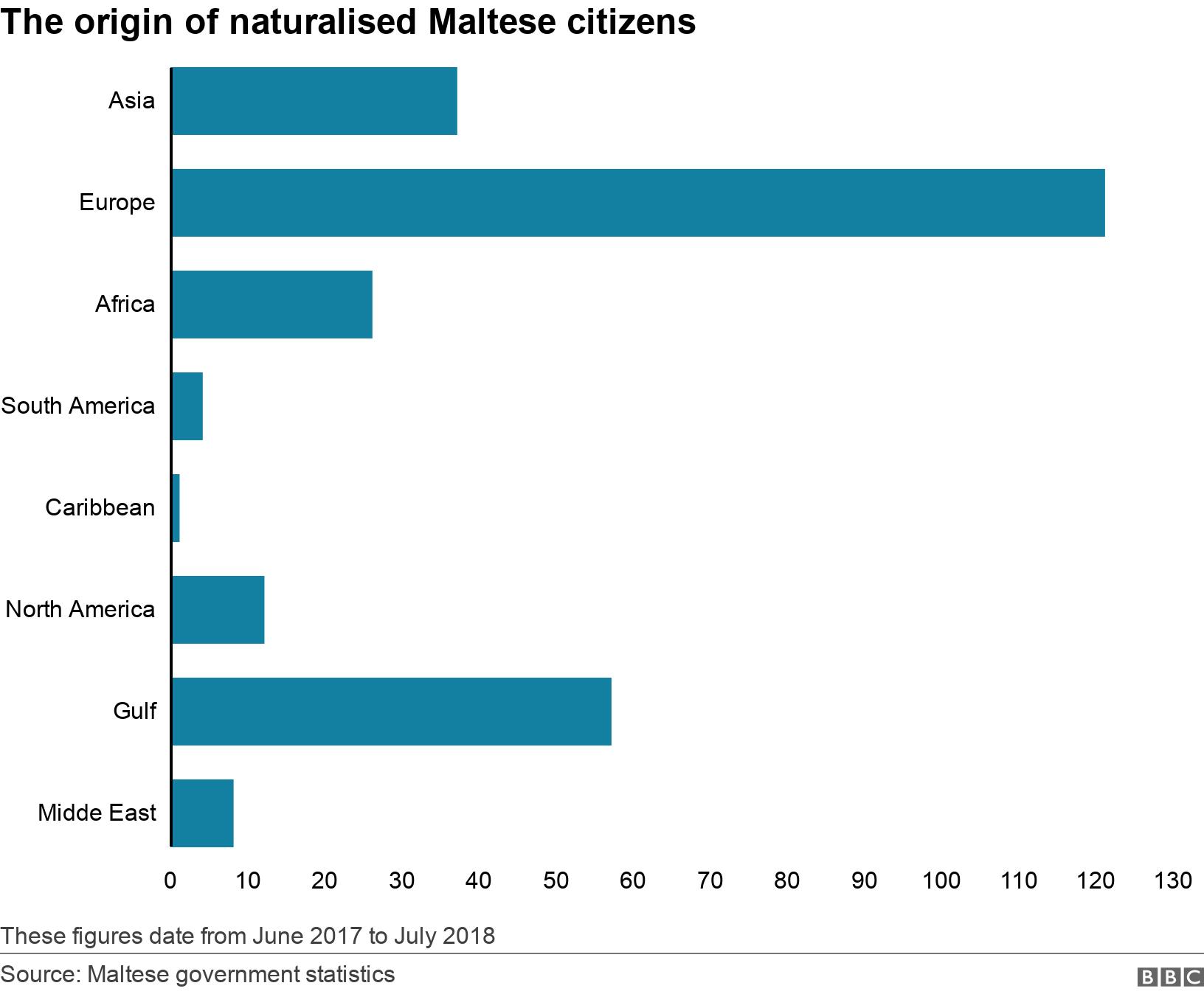

The Maltese government doesn't release information on the individual countries of origin of those applying for "golden passports", but it does give information by region.

Europe is the most common region of origin followed by the Middle East and Gulf region, and Asia.

However, EU member countries are obliged to publish figures of annual citizenship acquisitions - who has become a citizen that year.

Protesters holding a photo of murdered reporter Daphne Caruana Galizia, who was investigating the sale of Maltese passports

After the introduction of the policy in Malta in 2014, there was an increase in the number of naturalised citizens from Saudi Arabia, Russia and China.

For example, Saudi Arabia didn't contribute any naturalised citizens before 2015, but since then there's been more than 400.

There are legitimate reasons for seeking another passport, but there are allegations the Maltese system is being abused.

The European Commission published a report in January 2019, external saying that it had concerns about Malta's scheme, which was "less strict" than other EU countries.

For instance, the applicants are not obliged to have physical residence and there is no requirement to have prior connections to the country.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) released a report in 2018 that blacklisted Malta as a country at high risk of tax evasion because of its "golden passport" scheme.

The Maltese government says it screens all applicants and politically exposed persons.

Mr van der Baaren says many families may use it to educate their children abroad or to have it in case they need to relocate from their home country. But he adds: "The programmes can also exacerbate inequalities in the countries of origin, as it enables an elite few to buy a second citizenship."

In the EU, Cyprus and Bulgaria have similar schemes.

Between 2008 and 2018, Cyprus granted citizenship to 1,685 investors and 1,651 members of their families. Although in November, the country stripped 26 investors of their "golden passports" citing "mistakes" made in the processing of them.