Macron pension reform: Why are French workers on strike?

- Published

Port workers with smoke canisters march in Marseille against France's pension reform plan

France's biggest strike in decades has shut down public transport services and reduced the number of hospital staff, teachers and police officers at work in the latest protest against President Emmanuel Macron's reforms.

In this case, unions representing millions of staff in both the public and private sectors are unhappy about a plan to overhaul the country's pension system, which they say will force people to work longer or face reduced payouts when they retire.

One opinion poll put public support for the latest strike action at 69%, with backing strongest among 18-34 year-olds.

So why is Mr Macron looking to implement such unpopular new measures - and just how controversial are they?

What's Macron up to?

Well, France currently has a complex system of 42 different pension schemes for its private and public sectors, with variations in retirement age and benefits. Mr Macron wants to create a unified system.

Pension benefits are largely calculated using an employee's 25 highest-paid years of work in the private sector, while in the public sector it is based on payments made in the last six months before retirement.

The French president's new plan aims to reward employees for each day worked, earning points that would later be transferred into future pension benefits.

Millions of people are expected to take to the streets in protest across France that could last days

In November, a report commissioned by France's Prime Minister Edouard Philippe concluded that, under the existing system, the country's pension deficit could be as high as €17.2bn ($19bn; £14.5bn) by 2025.

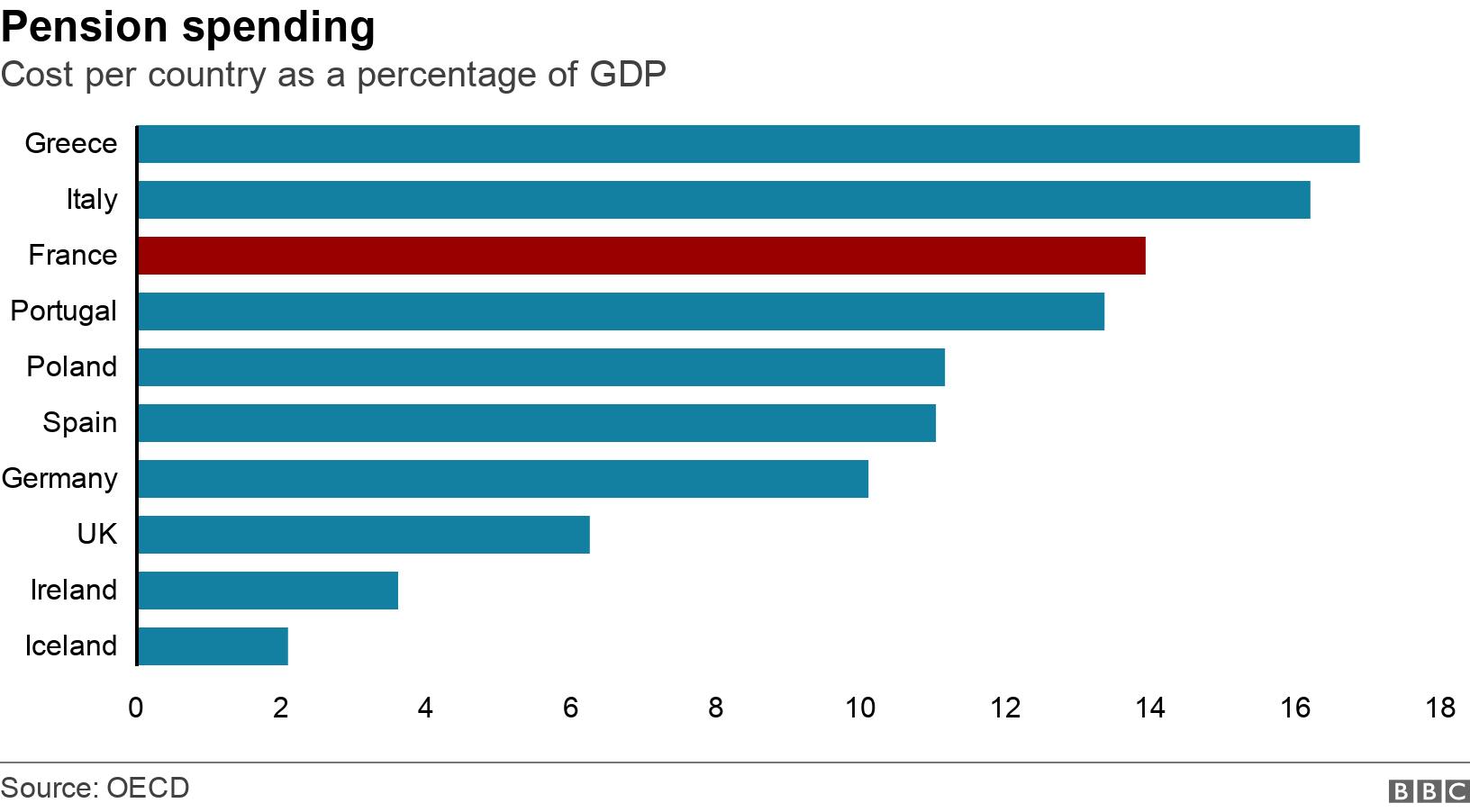

The cost of France's current system, in terms of public spending as a percentage of GDP (the country's entire economic output), is among the highest in the world - at 14%.

Mr Macron, aware of France's ageing population, has said his universal pension plan would be fairer than the current system.

The age at which citizens can start drawing a pension varies across the European Union (EU).

The official retirement age in France has been raised in the last decade from 60 to 62, but remains one of the lowest among the OECD group of rich nations - in the UK, for example, the retirement age is 66.

So how controversial is his plan?

The move to a universal points-based pension system would remove the most advantageous pensions for a number of jobs ranging from sailors to lawyers and even opera workers.

While Mr Macron has not suggested immediately increasing the age of retirement from 62, those retiring before 64 would receive a lower pension based on the points earned.

For example, someone retiring at 63 could receive 5% less, so unions fear it will mean having to work longer for a lower pension.

Public sector workers who do arduous or dangerous jobs can also retire years earlier under the current system.

But metro workers, for example, say reforms would force them to work longer by effectively taking away their right to retire early, negotiated decades ago to compensate for having to work long hours underground.

One of France's largest unions, CFDT, said its mostly private sector members would not be participating in Thursday's strike.

CFDT, considered to be one of the more moderate unions, has previously said that reform was needed because the current pension system was not sustainable. The union has also said that a credit-based system might actually improve retirement payments for women.

Mr Macron's new system would not penalise workers who take time off due to illness or maternity leave, offering compensation points.

A recent poll concluded that 75% of people thought that pension reforms were necessary, but that only a third believed the government could deliver them.

On the first strike day Paris saw a large march and clashes with police

Despite the public understanding of the need for change, the latest strike action has overwhelming support. It is expected to last beyond Thursday and some trade union leaders have warned they will keep it up until Mr Macron abandons his campaign promise to overhaul the retirement system.

The Macron administration will be hoping to avoid a repeat of the country's general strike over pension reforms in 1995, which crippled the transport system for three weeks and drew massive popular support, forcing a government reversal.

Does France lead Europe with strike action?

We hear a lot about demonstrations in France relating to grievances over pay and conditions at work, from Uber drivers striking in Paris to widespread "gilets jaunes" (yellow-vest) protests - but large nationwide strikes involving both private and public sector workers are less common.

A lack of official data and differences in the methods used by countries to record levels of industrial action make it hard to determine whether France leads the way.

According to figures collated by the OECD between 2008 to 2015, France is second only to Denmark on a list of European nations with the most working days affected by strike action. Belgium is third.

French statistics agency Dares reported in 2017 that employers in France lost more than 300 days per 1,000 employees. In 2014 it was 69 days, according to Dares.

Separately, the European Trade Union Institute recently published a "strike map", external showing the number of "days not worked" in France between 2010 and 2017 was on average 125 per 1,000 employees. For Spain the number was 50 and for the UK just 20 days.

In Spain, though, strike action is often not recorded or counted, and in countries such as Italy and Greece the data is said to be unreliable.

- Published16 November 2019

- Published13 September 2019

- Published9 April 2019