RIC commemoration: 100-year-old war wound that came back to bite

- Published

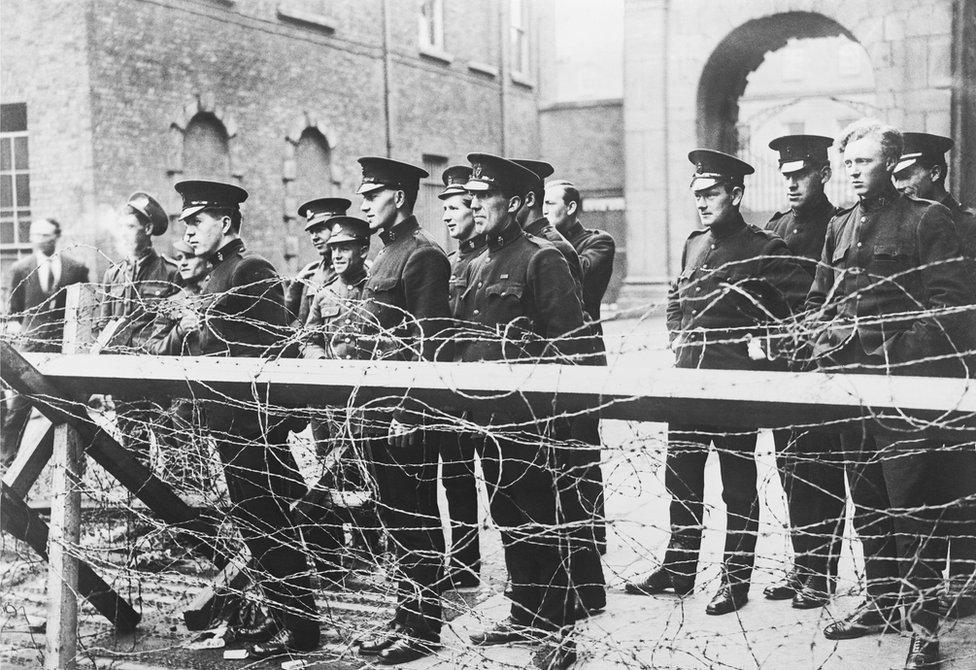

Royal Irish Constabulary men at Dublin Castle, shortly before the force was disbanded in 1922

Dublin Castle, once the headquarters of British rule in Ireland, was supposed to host a state commemoration for pre-partition police forces on Friday.

But the Irish government shelved its centenary event for the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) and Dublin Metropolitan Police (DMP) following days of controversy.

Critics accused the government of trying to whitewash the history of the RIC and that of its notorious special reserve, nicknamed the Black and Tans.

But Justice Minister Charlie Flanagan argued thousands of officers served their communities with honour and should not be airbrushed from history, external.

BBC News NI speaks to two historians, both related to RIC men, who hold very different views on how the Irish state should remember those who enforced the law before independence.

'It's time to put the emotional baggage behind' - Madge O'Boyle

Madge O'Boyle's great uncle, RIC Constable Charles McGee, was the first Irish policeman killed in the 1916 Easter Rising.

She believes the current criticism of the RIC is very unfair and "shows an ignorance of facts of history".

"It is wrong to brand them all as aggressive people who were against anything that was Irish," she said.

Her great uncle was an Irish-speaking Catholic from County Donegal who joined the RIC in 1912 during the campaign for Home Rule.

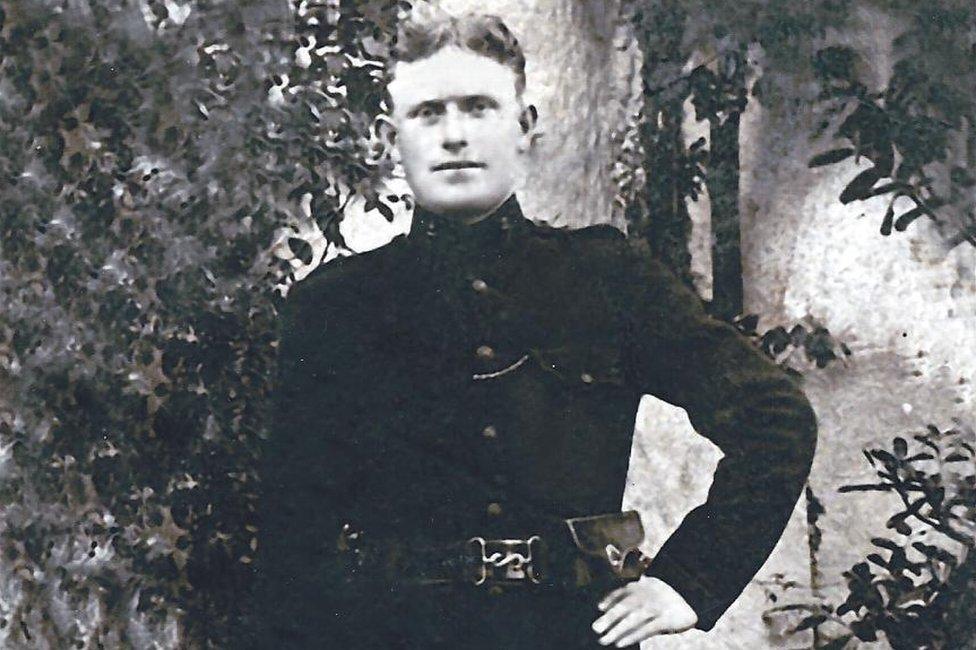

Charles McGee was the first of more than 500 policemen killed in Ireland between 1916 and 1922

On the first day of the 1916 rebellion, the unarmed 23-year-old constable was shot near Castlebellingham, County Louth.

Ms O'Boyle believes he was hit by a stray bullet after confronting rebels who were "commandeering" food from local shops.

In the turbulent decades that followed, her family barely spoke of the young policeman, until Ms O'Boyle began to research his story in the 1980s.

She eventually published a book about him and, in 2016, she was among invited guests at Dublin's official Easter Rising centenary.

At the time, she told the BBC she was proud her great uncle had "finally been recognised after 100 years" as until then only rebels had been commemorated.

In 2016, Ms O'Boyle spoke of her pride in commemorating her great uncle

Ms O'Boyle was due to attend the Dublin Castle ceremony on Friday, until it became the first public relations casualty in the government's Decade of Centenaries programme. , external

She said she was "very disappointed" by the furore, particularly from opposition politicians.

"It seemed like an outburst of deeply ingrained historical anger, rather than a sensible and logical assessment of the situation" she said.

"They must remember their commitment to the Good Friday Agreement and their pledge to recognise the existence of both traditions on the island of Ireland.

"Bigotry is best left to 100 years ago."

Much of the criticism of the commemoration focused on the RIC's reserve forces, the Black and Tans and the Auxiliaries.

Comprised mainly of former World War One soldiers from England, they were recruited to bolster RIC ranks during the War of Independence.

Both forces were deeply resented because of their violent reprisals on civilians in the aftermath of IRA attacks.

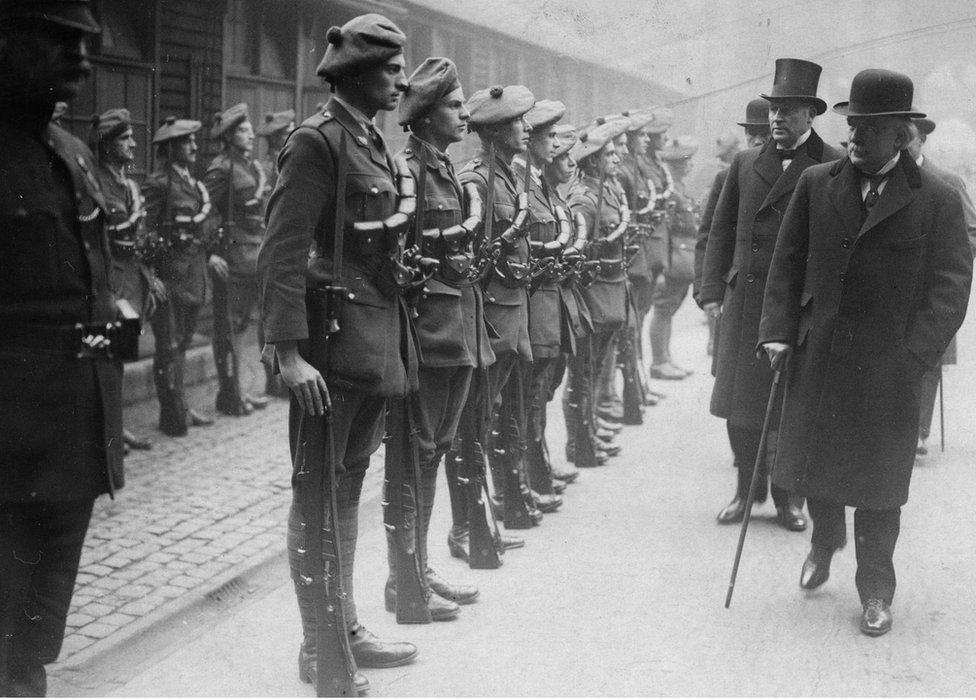

British PM David Lloyd George inspecting officer cadets of the RIC's Auxiliary Division in 1920

Ms O'Boyle said she too would be "uncomfortable about honouring the Black and Tans" and that the government "should have been clearer" that it intended solely to commemorate the RIC and DMP.

"I'm a historian and I know how undisciplined and out of control the Black and Tans were sometimes," she said.

However, she is still hopeful the deferred ceremony for the RIC and DMP will go ahead at some point.

"While my background as Irish teacher would be nationalist, I am in favour of recognising the efforts of honourable policemen who worked to maintain peace and order in Irish society," she explained.

"This is 2020, so I think it's time to put the emotional baggage behind and recognise people from both traditions on the island."

'Commemorating oppressors of the Irish people'- Kerron Ó Luain

Historian Kerron Ó Luain was among the many people who criticised the state commemoration on social media.

The 32-year-old Dubliner said there is a "collective memory of the words Black and Tans in the Irish psyche" which explains why the event touched such a raw nerve.

A Black and Tan soldier on a vehicle piled with commandeered items during a raid on a union HQ

Mr Ó Luain is a great-grandson of RIC sergeant William Lambe, who policed Claremorris, County Mayo, in the early 1900s.

But he said he opposes a state commemoration for "colonial police forces" like the RIC and DMP.

He also dismissed suggestions the RIC could ever be commemorated in isolation from its special reserve.

"What several historians have pointed out is that the Black and Tans were actually incorporated into the RIC," he explained.

"There's stories passed down - from grandparents through the generations - of the war crimes and massacres that the Black and Tans had taken part in.

"It's still in the collective memory even if there was no familial link - incidents like the burning of Cork, the burning of Balbriggan and so forth."

Cork city in 1920 after the Black and Tans and Auxiliaries set fires in retaliation for IRA attacks

Mr Ó Luain accused the government of trying to "spin" the controversy by saying the ceremony was only for the RIC and DMP, arguing both forces oppressed their fellow citizens.

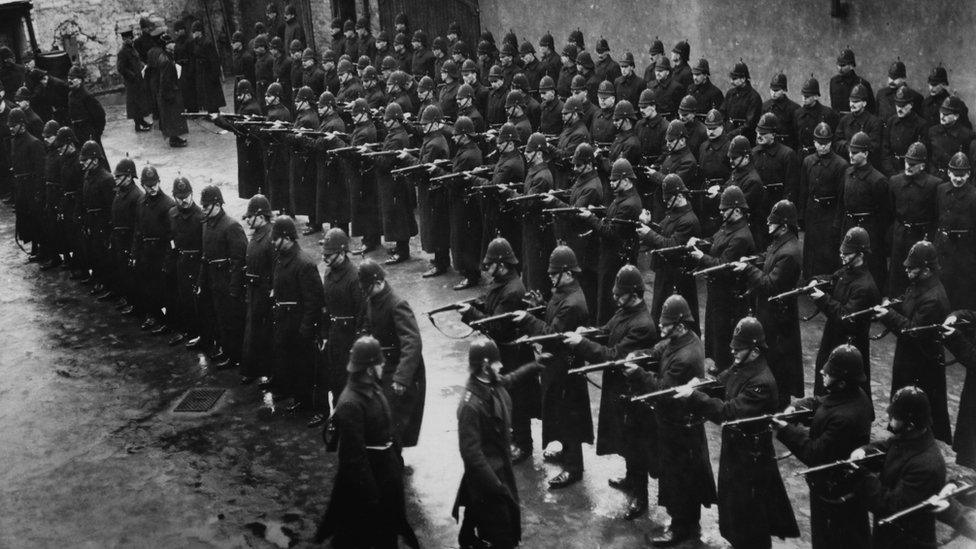

He cited examples such as the RIC assisting the exportation of food out of Ireland during the famine, and the DMP clashing with striking workers during the 1913 Lockout.

Regarding his own RIC heritage, Mr Ó Luain admitted he knows little of his paternal great-grandfather or his role in the force.

"I actually don't know much about him to be honest. I've never researched him, funnily enough for a historian," he said.

"I've never gone down the genealogy track, mainly because I don't think that what our relatives did prior to us should determine our political stance in the here and now.

"We have to understand the past of course, but we don't have to take our lead from people just because we were related to them in some bygone time."

As for the deferred ceremony, Mr Ó Luain wants it cancelled altogether.

"People are entitled to hold their own private commemorations in cemeteries; at monuments; wherever, but I think there's a marked difference between that and a state-led commemoration," he said.

"It was imposing a false consensus on the people - essentially commemorating oppressors of the Irish people."

- Published8 January 2020

- Published7 January 2020

- Published28 March 2016