Yalta: World War Two summit that reshaped the world

- Published

The Big Three - Winston Churchill, Franklin Roosevelt and Joseph Stalin

In February 1945, three men met in a holiday resort to decide the fate of the world.

Nazi Germany was on its knees. Soviet troops were closing in on Berlin, while Allied forces had crossed Germany's western border. In the Pacific, US troops were steadily but bloodily advancing towards Japan.

As their armies poised for victory, the so-called Big Three - US President Franklin Roosevelt, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Soviet leader Joseph Stalin - agreed to meet in Yalta, a Soviet resort on the Black Sea.

At the end of the bloodiest conflict the world had ever known, 75 years ago, the Allies wanted to stop such devastation from ever happening again.

But both the US and the USSR wanted co-operation on their own terms. Despite the Yalta agreements, within months the stage was set for the Cold War - the struggle between the two new superpowers that split the globe into ideological camps for decades.

Watch footage of the Big Three at Yalta in 1945

"If the goal at Yalta was to lay the basis for a genuinely peaceful post-war order, then the conference failed," Prof Andrew Bacevich at Boston University told the BBC. "But given the contradictory aspirations of the US and USSR, that goal was never in the cards."

What was happening in February 1945?

By the start of 1945 Nazi Germany had lost the war. The country maintained its bloody and increasingly desperate resistance, but the result of the conflict was no longer in doubt.

In eastern Europe, the Soviet Union had turned the tide and shattered Germany's armies after four years of savage warfare.

But while the USSR was militarily triumphant - about three-quarters of all German troop casualties in the war died on the Eastern Front - the country had suffered terribly.

After more than three years of war, the Soviet Union had crushed Germany's forces and was just miles from Berlin

It is estimated that one in seven Soviet citizens, some 27 million people, died in the conflict - two-thirds of whom were civilians. Some academics put the numbers even higher.

The country's cities and richest lands were devastated by the conflict. Industry, farms, homes and even roads had been wiped from the landscape.

What were the leaders' goals?

Joseph Stalin was determined to get his country back on its feet. He came to Yalta seeking a sphere of influence in eastern Europe as a buffer zone to protect the USSR. He also wanted to divide Germany, to ensure it could never pose a threat again, and to take huge reparations - in money, machinery and even men - to help his shattered nation.

Stalin knew he would need the acceptance of the Western powers to achieve this.

Winston Churchill understood Stalin's goals. The pair had met in Moscow in October 1944, and discussed the idea of carving Europe into spheres of influence for the USSR and the western powers. He also understood that the millions of Soviet troops that had pushed Germany out of central and eastern Europe far outnumbered the Allied forces in the west - and there was nothing the UK could do if Stalin chose to keep them there.

Poland's eastern border with the USSR was not finalised until the early 1950s

The UK had declared war in September 1939 because Germany had invaded its ally, Poland, and Churchill was determined to ensure the country's freedom. The UK however had also paid a heavy price for victory, and was now essentially bankrupt. Churchill hoped the US would support him and stand up to Stalin.

But US President Roosevelt had his own priorities. He wanted Stalin to sign up to the United Nations - a new global peacekeeping body for the post-war world.

Prof Melvyn Leffler at the University of Virginia told the BBC that Roosevelt was well aware how acrimony between allies after World War One had led the US to step back from world politics in the 1920s and 1930s. "What Roosevelt wanted most of all was to avert a return to American isolationism," he said.

The president also wanted the Soviet Union to declare war on Japan. Though the tide had dramatically turned against the Japanese Empire, their forces were still inflicting heavy casualties on advancing US forces in the Pacific. Anxiety about a bloody invasion of the Japanese home islands loomed large in US strategic thinking.

What happened at Yalta?

Although Roosevelt wanted to meet somewhere in the Mediterranean, Stalin - who had a fear of flying, external - instead offered up Yalta. Group talks took place between 4-11 February at the US delegation's residence, Livadia Palace, which was once the summer home of Russia's last Tsar, Nicholas II.

The three leaders had met before, at Tehran in 1943. Roosevelt was more willing to trust Stalin than was Churchill, who saw the Soviet leader as an increasingly dangerous threat.

The group talks at the Yalta summit took place at the Livadia Palace

After a week of talks, the Big Three announced their decisions to the world. Following its unconditional surrender, Germany would be broken apart. The leaders agreed in principle to four occupation zones, one for each country at Yalta and also for France, and the same division of Berlin.

A declaration also said Germany would pay reparations "to the greatest extent possible", external, and a commission would be created in Moscow to determine how much they owed.

The leaders also agreed to democratic elections throughout liberated Europe - including for Poland, which would have a new government "with the inclusion of democratic leaders from Poland itself and from Poles abroad". The Soviet Union had already placed a provisional Communist government in Warsaw, which they agreed would be expanded.

But democracy meant something very different to Stalin. Though he publicly agreed to free elections for liberated Europe, his forces were already seizing key offices of state across central and eastern European countries for local communist parties.

Moreover, the leaders decided - at Stalin's urging - that Poland's borders were to move westward, giving land to the USSR. The Baltic States would also join the Soviet Union.

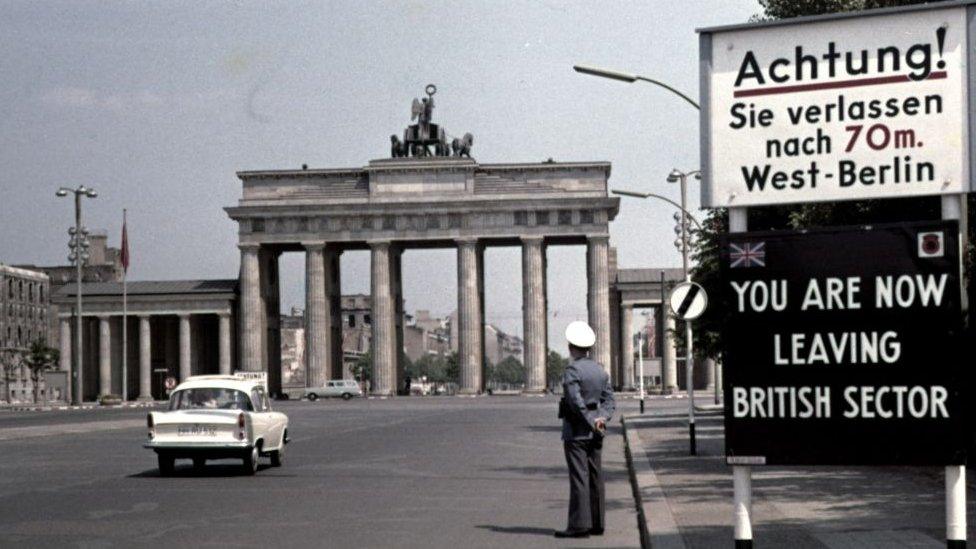

Berlin was a divided city until 1989

Historian Anne Applebaum wrote in her text Iron Curtain that the leaders "decided the fate of whole swathes of Europe with amazing insouciance". Roosevelt "half-heartedly" asked Stalin if the city of Lwow might stay a part of Poland, but did not push the idea, and it was quickly dropped.

Roosevelt was more focused on his plan for the United Nations, and he got his wish. All three nations agreed to send delegates to San Francisco on 25 April 1945, to help set up the new international organisation. What's more, Stalin pledged to launch an invasion of Japan three months after the defeat of Germany.

Churchill remained deeply concerned about the situation in eastern Europe after the summit, despite the agreements. He urged his forces and the Americans to move as far east as possible before the end of the war.

What happened afterwards?

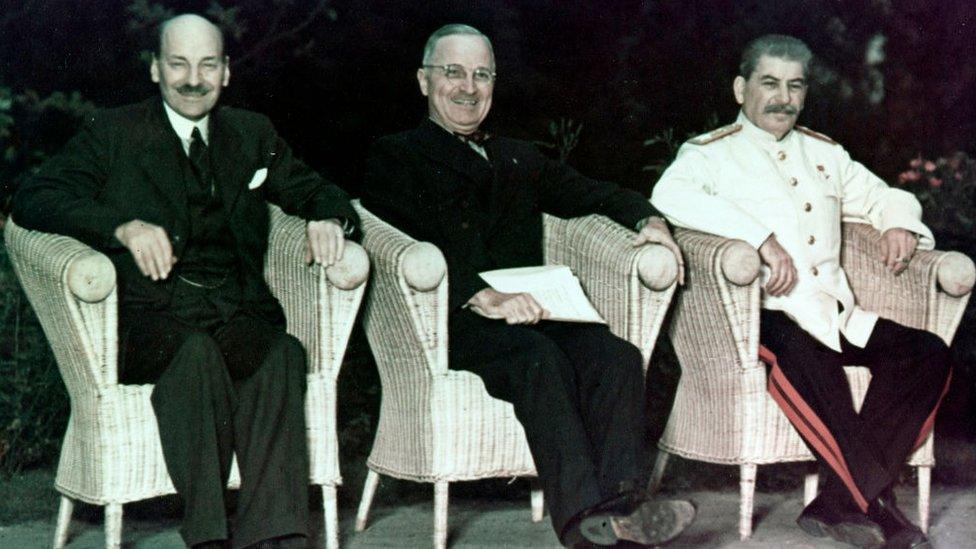

Within months, the political situation had changed dramatically. Roosevelt died of a massive brain haemorrhage in April, and was replaced by Harry Truman. Germany surrendered unconditionally in May. And on 16 July, the US successfully tested its new secret weapon - the nuclear bomb. The very next day, President Truman met Winston Churchill and Joseph Stalin at the Potsdam conference outside Berlin.

Truman did not know Stalin, and had been president for just four months. Winston Churchill, in power since May 1940, was replaced halfway through the conference by Clement Atlee after the 1945 general election.

Clement Attlee, Harry Truman and Joseph Stalin met at Potsdam after the end of the war in Europe

The mood at the conference was very different. US policymakers felt more confident after realising the power of the atomic bomb. Truman was far more sceptical of Stalin than Roosevelt had been. He and his advisers believed the USSR had no desire to stick to the Yalta accords.

In less than two years, the US president announced the so-called Truman Doctrine, which pledged US power to contain Soviet expansion efforts around the world. The Cold War had begun.

Both Churchill and Roosevelt were later criticised for giving way to Stalin at Yalta. But practically, there was little the US and UK could do. Stalin already had troops throughout central and eastern Europe. After Yalta, Churchill commissioned a plan of attack against the USSR - codenamed Operation Unthinkable - but British military planners realised it was totally unrealistic.

Prof Leffler says that "what Yalta did in regard to eastern Europe was simply to acknowledge the power realities that existed at the time".

- Published31 December 2019

- Published31 August 2019

- Published23 August 2019

- Published12 July 2019

- Published18 April 2019

- Published21 June 2011