Irish election: Will Sinn Féin redefine Irish politics?

- Published

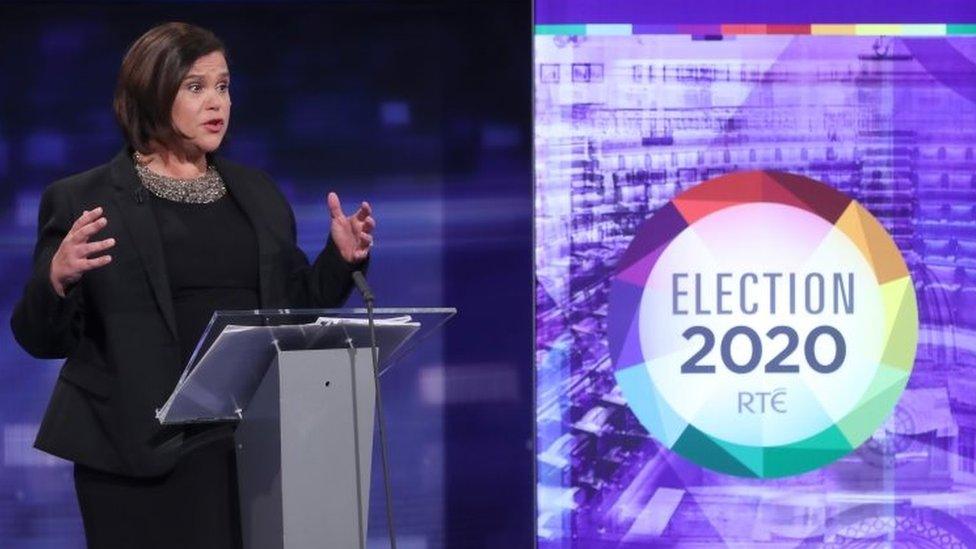

Sinn Féin president Mary Lou McDonald argues that voters now recognise her party as a real alternative

A cosy old establishment. A growing gap between elites and governed. Inequality worsening. Populism on the rise.

It might be a familiar song across Europe and the West - but in Ireland these tunes are brand new.

Sinn Féin, an old party, seems to have a new mission. After years of life at the political fringes, it leads the latest Irish general election polling.

Though well known in the UK, "the Shinners" have had a minor role in the political life of the Republic.

Politics south of the border, has been an outlier in European terms, dominated by two hegemonic centre right parties, Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, who, frankly, don't really disagree about very much. They've alternated in power for decades.

Political life has therefore been, though increasingly economically liberal, conservative too. There has been little space for the left, or equivalent radical force to break through.

In some senses, this is odd.

If we accept the analysis that a crucial underpinning of the populist waves we've seen in other countries has been a rejection of globalisation, then on the surface Ireland should have been at the front of the queue.

Arguably going all the way back to Seán Lemass in the 1960s, successive Irish leaders have sought to place the "Celtic Tiger" at the heart of the global economy, slash corporate tax rates and become one of the most open globalised economies on earth.

In many ways it has been a remarkable success story. One of Europe's most backward economies turned into a powerhouse, with many of the world's biggest companies headquartered in Dublin or Cork.

But it's come at a cost.

Increasingly, thousands of Irish feel left out. Rocketing rents, creaking social services and rampant inequality have made their mark.

Sinn Féin's new voters are the young and Dublin-based, suffering from housing problems in every direction.

Brexit too, though absent from the campaign, has made Irish politics "greener", in the old sense, reactivating certain Republican instincts, just at the moment a generation of voters come of age who remember little or nothing of the Troubles, the IRA and Sinn Féin's association with them.

The general election will be held on 8 February

In a peculiar way, this is both the normalisation and denormalisation of Irish politics at the same time.

If Sinn Féin does become a prominent player in the Dáil, then a more typical European left-right politics will have emerged at last.

But equally, Ireland and Irish politics will, to some extent at least, have its own dose of the populist politics which have so marked the early 21st Century, albeit an unusual populism of the left.

A party which says that they, not the long-time cosy duopoly of FF and FG, are the true guardians of the people's interests.

As one leading Irish politician put it to me: "The Sinn Féin rise is real. It's our Trump, Brexit, Lega, Le Pen or even our Corbyn. Everything is changing. There's a global theme."

The consequences of a radical Republican party in the Dáil, even if not in government, will be felt not only in Dublin - but Belfast, London and perhaps Brussels too.

The two main parties will do everything they can to keep SF out and refuse to work with them.

But perhaps, in the long term, that will prove impossible. Sooner or later, the great Irishman WB Yeats once said, "things fall apart- the centre cannot hold".

- Published3 February 2020

- Published3 February 2020

- Published14 January 2020

- Published14 January 2020