Syria war: Refugees eye Europe as Turkey hits breaking point

- Published

Syrian refugee Halil is one of thousands waiting on the Turkish coast to get to Greece

Halil stands on a small, deserted beach on the western coast of Turkey, at the edge of the water. "Look! it's so close" he says, "but reaching it is so hard."

The Greek island of Samos is clearly in sight, only a few miles away.

Halil fled Syria for Turkey four years ago, and he's lived here since, with his wife, mother and five young children.

But last week he gave a smuggler the little money they had, to take them to Greece.

"I haven't had a job in a year so my financial situation is bad. I'm the only one who can work. If I'm stuck at home, my children can't eat. What choice do I have?"

Halil has lived in Turkey with his family since he fled from Syria four years ago

But his attempt to escape failed.

"We heard shouting and we realised the Turkish soldiers had found us. They captured all of us, they didn't let anyone escape."

During the 2015 migrant crisis, Turkey struck a deal with the European Union. It agreed to stop refugees from reaching Europe in return for billions of euros.

For years that deal has held, with Turkish guards policing the borders and patrolling the sea.

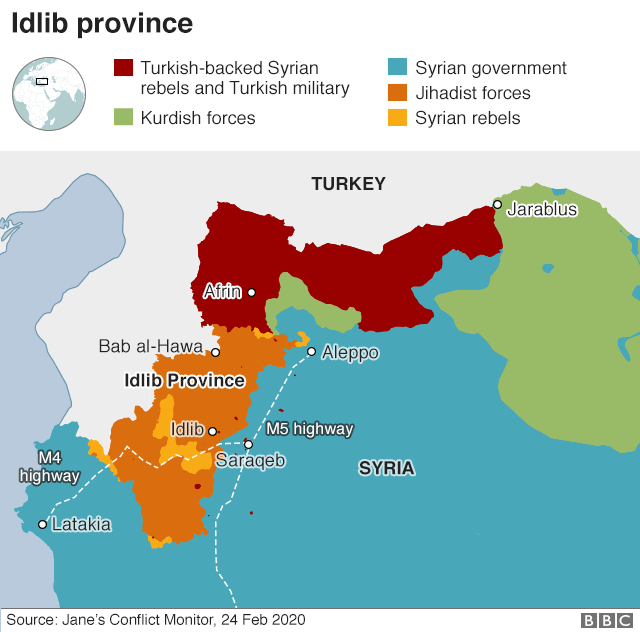

But on Thursday night, following the killing of dozens of Turkish soldiers in an airstrike in Idlib, Turkey said it was opening its western land and sea borders to allow migrants and refugees to travel on.

Migrants head for Turkey's EU borders

Turkey has taken in 3.7 million Syrian refugees since the start of the war. For months President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has been threatening to send some of them to Europe unless Turkey gets more help in Syria.

"The refugee crisis is growing, it's getting worse," his chief adviser, Ibrahim Kalin, told the BBC.

Ibrahim Kalin, top aide to President Erdogan

"For many European countries their approach seems to be that as long as they don't come our way, they don't come to our cities, it's somebody else's problem."

Turkey is coming under increasing pressure. There are nearly a million people stuck along its border with Syria, who have been displaced by the recent fighting, and whom Turkey won't let in.

We're taken out there by Abdullah al-Hussein, the head of the White Helmets rescue organisation in the opposition-held Syrian province of Idlib. "The land is shrinking and the number of people is growing," he says.

"We're asking the international community, not just Turkey, to open their borders to the civilians of Idlib, otherwise there will be a massacre. A big one."

Back along the coast we find thousands of Syrians living in makeshift settlements, without even basic facilities.

They are exploited for cheap agricultural labour. Some tell us they earn as little as £5 ($6; €6) a day. All of them are desperate to escape to Europe.

"I tried to get out four times but every time I was caught," Fathi tells us.

Thousands of Syrians are living in makeshift settlements along the coast of western Turkey

"I don't have any money left, but if I did, I would keep trying. I've spent everything. I even sold my wife's gold."

Now the boats bound for Greeks islands are filling up, as the Turkish coastguard appears to turn a blind eye.

Upon hearing the news that guards were no longer pushing people back, hundreds started making their way to the border.

There are networks of smugglers, primed and ready to take people across. Some are openly advertising on social media and one of them agrees to talk to us on the phone.

"We send about two or three boats a day when the sea is calm," he tells us. "We're not being watched as much at the moment," he says. "It's not as risky to cross."

Halil remains determined to reach Greece despite the large number of migrants in Greek migrant camps

The Turkish government has said there has been no change to its refugee policy, but that the influx of migrants from Turkey towards Europe may continue if the situation in Idlib continues to worsen.

Greece has stepped up police patrols at its border checkpoints, but for now the road to Europe looks easier.

Halil is determined to try again. "I'll do it all over again, until I get out," he says as his mother bursts into tears beside him.

You don't want him to go? I ask. "Oh, let him try, he can't feed his children here."

- Published18 February 2020