Syria war: Why does the battle for Idlib matter?

- Published

A humanitarian catastrophe is unfolding in north-western Syria, where the government of President Bashar al-Assad is trying to recapture the opposition-held province of Idlib.

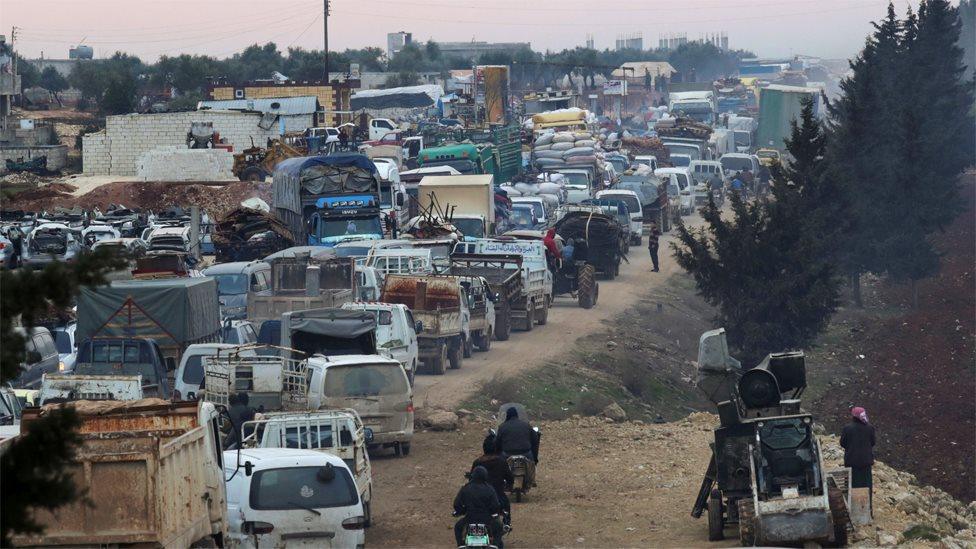

Government air strikes and ground operations have driven almost a million civilians from their homes since December - the biggest single displacement of Syria's nine-year war.

The UN has said a full-scale battle for Idlib could result in a "bloodbath".

What's so important about Idlib?

The province - along with parts of Hama, Latakia and Aleppo - is the last stronghold of the rebel and jihadist groups that have been trying to overthrow President Assad since 2011.

The opposition once controlled large parts of the country, but the Syrian army has retaken most of the territory over the past five years with the help of Russian air power and Iran-backed militiamen. Now, the army wants to "liberate" Idlib.

Rebels and jihadists seized control of the city of Idlib in 2015

In recent years an influx of desperate displaced people has doubled its population to about three million, including one million children.

Idlib is also strategically important to the government. It borders Turkey to the north and straddles highways running south from the city of Aleppo to the capital Damascus, and west to the Mediterranean city of Latakia.

Who controls the province?

Idlib had been controlled by a number of rival factions, rather than a single group, since it fell to the opposition in 2015. But the dominant force is the al-Qaeda-linked jihadist alliance, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS).

HTS was set up in 2017 by a group that broke off formal ties with al-Qaeda. It is designated as a terrorist organisation by the UN.

Hayat Tahrir al-Sham is the dominant armed opposition group in Idlib

In January 2019, HTS staged a violent takeover of large areas of the province. It expelled some rebel fighters to Aleppo's Afrin region, which is controlled by factions supported by Turkey.

A UN committee estimated in January that the group had between 12,000 and 15,000 fighters in Idlib and its surrounding areas, external.

In the battle against the government offensive it is supported by a variety of forces - including Chinese Uighur militants, a new al-Qaeda affiliate and Islamist groups fighting under the banner of the Turkey-backed Syrian National Army.

The Islamic State group (IS) has several hundred fighters in Idlib. But other factions actively oppose its presence.

What led to the current government offensive?

Idlib has been subject to a "de-escalation" agreement between Turkey, Russia and Iran since May 2017. It called for the cessation of hostilities in four opposition strongholds, including Idlib, the "separation" of jihadists and mainstream rebels inside them, and unhindered aid deliveries.

Syrian government and Russian air strikes have devastated opposition-held areas

That October, Turkey deployed troops to observation posts on the opposition-held side of the front line in Idlib to monitor the agreement. Russian troops did the same on the government side. However, their presence did not stop the Syrian army retaking a large part of eastern Idlib's countryside over the next four months.

The government then turned its attention to opposition bastions further south - notably Homs province, and the Eastern Ghouta near the capital Damascus.

All those were recaptured by July 2018, devastating residential areas, killing hundreds of civilians, and displaced hundreds of thousands. Many opposition supporters were "evacuated" to Idlib as part of negotiated surrenders.

The 2018 Sochi accord was agreed by the Turkish and Russian presidents

Troops then began preparing for an all-out assault on Idlib. But one was averted in September 2018 by an agreement between Turkey and Russia.

The Sochi accord called for a "demilitarised buffer zone" along the front line. Mainstream rebels were required to pull their heavy weapons out of the zone, and jihadists were told to withdraw altogether.

However, it was never fully implemented. Rebels reportedly withdrew some heavy weapons, but the jihadists stayed.

Hospitals, schools, bakeries and other critical civilian infrastructure have been attacked

Hayat Tahrir al-Sham's takeover of Idlib a year ago was followed by renewed fighting. Government and Russian warplanes stepped up strikes on opposition-held areas, while jihadists shelled government-held territory.

In April 2019, the army launched what Russia called a "limited" offensive in northern Hama and southern Idlib. The UN said 500 civilians were killed and 400,000 displaced over the next four months before a ceasefire was declared.

The Syrian army has recaptured several major towns in recent months

A further 900,000 civilians - the vast majority of them women and children - have fled since the current government assault began in December, according to the UN. Some 300,000 have been displaced in February alone.

The Syrian army has recaptured major towns in southern Idlib and regained control over the Aleppo-Latakia (M4) and Aleppo-Damascus (M5) highways. Those displaced have meanwhile moved north and west to the ever-shrinking space considered safe near the Turkish border.

Turkey, which has sent military observers to Idlib, wants the Syrian army to pull back

Turkey, which already hosts 3.6 million Syrian refugees and is worried about another influx, has given the Syrian army until the end of February to withdraw behind the line of Turkish observation posts or face military action.

Turkey has already sent thousands of reinforcements to Idlib and there have been deadly clashes between Syrian and Turkish forces. But President Assad has vowed to continue the offensive to bring the opposition enclave back under his control.

What is happening to the civilians?

UN Emergency Relief Co-ordinator Mark Lowcock warned that the crisis in north-western Syria had "reached a horrifying new level".

The number of civilians on the move in Idlib province continues to rise

"[The displaced civilians] are traumatised and forced to sleep outside in freezing temperatures because camps are full. Babies and small children are dying because of the cold," he said.

Mr Lowcock described the violence as "indiscriminate", with health facilities, schools, mosques and markets being hit. "Humanitarian workers themselves are being displaced and killed," he added.

Displaced Syrians are facing snow, bitter winds, icy rain and winter storms

The UN is calling urgently for tents, thermal blankets and clothing, as well as specialist counselling to help deal with trauma.

Mr Lowcock said "the biggest humanitarian horror story of the 21st Century" would only be avoided if those countries with influence in Syria brokered a ceasefire.

Last year, he warned that an all-out assault on Idlib could result in "the loss of huge numbers of people - running into hundreds of thousands, possible even more".