Coronavirus: Can EU get a grip on crisis?

- Published

Belgian Prime Minister Sophie Wilmès was among the European leaders taking part in the EU video call

"The EU is finished," gloat the nay-sayers. "Even faced with the coronavirus, its members can't stick together."

Certainly EU leaders meeting on Thursday - by socially-distant video conference - glaringly failed to agree to share the debt they are all racking up fighting Covid-19.

From her flat in Berlin, where she is self-isolating after her doctor tested positive for the virus, German Chancellor Angela Merkel openly admitted to the disharmony over financial instruments.

What leaders did agree on was asking Eurogroup finance ministers to explore the subject further, reporting back in two weeks' time.

Two weeks.

The EU is famous for kicking difficult decisions down the road but in coronavirus terms, with spiralling infection and death rates, two weeks feels like an eternity.

For ordinary people, frightened for their health, the safety of their loved ones, worrying about their rent and feeding their family after businesses shut down, the idea that Europe's leaders spent six hours on Thursday night, squabbling over the wording of their summit conclusions in order to defer a key decision over coronavirus funds, will be incomprehensible.

Spain and Italy - ravaged by the effects of the virus on their populations and their limited public finances - were deeply disappointed. Italy was already one of the EU's most Eurosceptic member states before Covid-19 hit.

A SIMPLE GUIDE: What are the symptoms?

AVOIDING CONTACT: Should I self-isolate?

VIDEO: The 20-second hand wash

Italian Twitter was littered with expletives on Thursday - and those were just the posts from politicians.

President Emmanuel Macron of France is said to have told leaders the political reaction after the crisis could spell the end of the EU.

The thing is, the coronavirus simply highlights already existing, well-known difficulties in the EU.

We need an intelligent strategy that at the same time protects the health of our citizens and keeps our economy afloat and our goods and cross-border workers moving

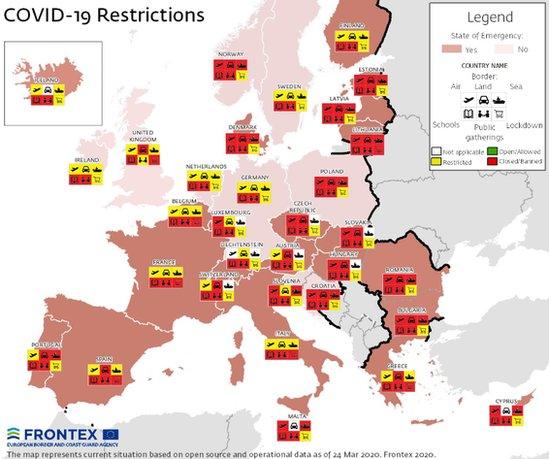

Firstly, the tension between centralising power in "Brussels" vs keeping decision-making with national governments/parliaments. Public health, for example is a national competency, which is why we've seen different EU countries taking different national measures to mitigate the effects of Covid-19.

And secondly, when it comes to economics, when wealthier countries like the Netherlands and Germany hear the words "debt-sharing" or "solidarity", what they worry that their voters will understand by that is - "richer EU countries in northern Europe have to foot the bill for poorer ones in the south".

When Schengen member Poland placed controls on its Schengen borders there were traffic queues of 75km (46 miles)

The Hague and Berlin never liked the idea of eurobonds. Calling them corona bonds now doesn't help warm them to the idea.

And the European Commission can't force the hand of national leaders.

Yet it's far too simplistic to write off the European Union.

When EU countries closed their national borders on one another during the 2015 migrant crisis, many predicted the bloc's demise but the EU muddled through. It's highly likely to scrape by again now, too.

It's also too lazy to say European unity has been entirely absent during the coronavirus crisis.

German hospitals like this one in Dresden are treating patients from Italy and France

"What do people mean when they talk of solidarity?" a politician from a wealthy northern European country said to me.

"Austria, France and Germany have all sent protective masks to Italy. Germany has taken in Covid-19 patients from Italy and neighbouring France. That is very clear solidarity."

EU leaders have also put in joint orders for new ventilators; they agreed two weeks ago to seal the external borders of the passport-free Schengen travel area and they are establishing priority access green lanes for delivery trucks at national borders so that exports and imports of food and medical supplies are no longer held up by virus-related travel restrictions.

The EU's border agency put up a graphic showing of the extent restrictions

Along with the rest of the G20 group of wealthy countries, the EU has agreed to invest in the search for a coronavirus vaccine to be made available the world over.

On the economic side, EU leaders agreed to allow governments the freedom to prop up businesses in trouble because of the coronavirus - throwing normally strict EU state aid rules out of the window.

The European Commission has also temporarily suspended eurozone rules on government debt, allowing member states to spend what they need to survive the outbreak as best as they can.

In addition, the European Central Bank announced a €750bn (£679bn) rescue package, declaring that "there are no limits" to its commitment to safeguard the euro.

It also said that there is "broad agreement" among EU countries to use the European Stability Mechanism, set up in 2012 on the back of the financial crisis, as a coronavirus crisis emergency fund - although predictably there are arguments among member states as to what conditions should be attached to the money.

We are talking about the EU, after all.

- Published26 March 2020

- Published27 February 2020

- Published30 June 2021

- Published28 February 2020