The 100-year wound that Hungary cannot forget

- Published

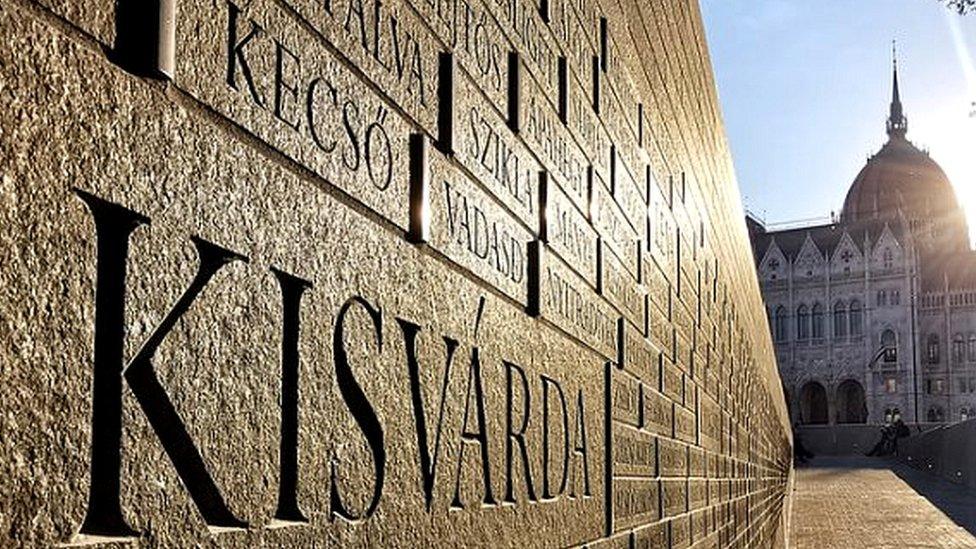

The new Monument of National Solidarity is directly in line with the main entrance of parliament

Exactly 100 years ago, in the Trianon palace at Versailles, two medium-ranking Hungarian officials signed away two thirds of their country, and 3.3 million of their compatriots.

A new monument has appeared in the past weeks in front of parliament in Budapest, among many already erected by Viktor Orban's government to Hungary's past glories.

For Hungary the 1920 treaty was a national wound that still festers to this day. Mr Orban's message to the world is that Hungary must now be respected. For his critics, he has dug deeper into that wound.

What Hungary lost in the Treaty of Trianon

As the Austro-Hungarian empire fell apart at the end of World War One, historic Hungary was forced to cede what is now Slovakia, Vojvodina, Croatia, part of Slovenia, Ruthenia, the Burgenland and Transylvania to the new states of Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia, to a much-enlarged Romania, and even to Austria, a fellow loser in the war.

Last month Viktor Orban posted a picture a Greater Hungary that included parts of Serbia, Romania, Slovakia and Croatia

US President Woodrow Wilson's proposal for the self-determination of all national minorities was valid for everyone except Hungary, claim the Hungarians.

National groups, which had long felt oppressed by the Hungarians, claimed their own sovereignty while Hungarians found themselves suddenly divided among several states.

Mainland Hungary was shaken from 1918 to 1921 by violence perpetrated both by occupying troops and by Hungarians against each other. Four months of communist "Red Terror" in 1919 was followed by the "White Terror", carried out by Adm Miklos Horthy's National Army militia.

Horthy was regent from 1920-44 and later refused to apologise for the atrocities, arguing that "only an iron broom can sweep the country clean".

Miklos Horthy allied with Nazi Germany and reclaimed part of Transylvania

Attempts to revise Trianon through the 1920s and 30s led directly to Hungarian participation in World War Two on the side of Nazi Germany.

Hitler was the only European statesman who offered them the return of territory.

What is the point of the new monument?

A national trench, or tomb, shelves gently beneath street level directly in line with the main entrance of parliament in Budapest.

Stainless steel letters depict the names of all the towns and villages of historic Hungary according to their size in the last, pre-war census in 1910. At the centre of the hard granite Monument of National Solidarity, is an eternal flame.

Place names from historic Hungary are listed on the monument in stainless steel

The anniversary of the Treaty of Trianon is a difficult balancing act for the Orban government.

By pursuing alliances with the governments of Serbia, Slovakia, the Czech Republic and Poland, Mr Orban is fond of saying that Hungary has broken out of its "hundred years of solitude".

What do the neighbours think?

But Romania, Ukraine, and to a certain extent Austria, watch his actions with distrust. Romania will this year celebrate the Trianon Treaty officially for the first time.

Flags will be placed at half-mast at this border post, where Hungary, Romania, and Serbia meet

"All these years we took note… of the many political statements coming from Budapest, which were very offensive for Romania," former Romanian foreign minister Titus Corlatean told the BBC.

He proposed the legislation, passed by the Romanian Parliament, to celebrate Trianon day. "I do not understand why the Romanians should be shy of marking what was fundamental for their history, because we don't want to offend anyone."

Apart from the monument, the Hungarian parliament will hold a commemorative session.

Church bells will be rung. And at 16:30 (14:30 GMT), at the request of liberal Budapest Mayor Gergely Karacsony - a fierce opponent of Viktor Orban - all transport will grind to a halt in the capital, as people observe a minute's silence.

A new musical will be performed in the Operett theatre, entitled They Tore It Apart. Nationalist group "Our Homeland" will distribute black armbands.

"We don't need to forget Trianon. That would be impossible," said the opposition Democratic Coalition party in a statement. "But mourning about Trianon can no longer be the focus of Hungarian politics, because, apart from the fact it leads nowhere, it paralyses, makes it incapable of action, it also consumes the moral and political power of the homeland."

"No other nation or country could have survived what happened to us 100 years ago. And we should be really proud of our existence," government spokesman Zoltan Kovacs told the BBC.

You may also be interested in:

Otto von Habsburg's heart was buried in Hungary in 2011; his body was buried separately in Austria

- Published25 February 2020