Olof Palme: Who killed Sweden's prime minister?

- Published

Olof Palme was assassinated on a Friday night walking down Sweden's busiest street

On a Friday night more than thirty years ago, Sweden's prime minister went to the movies.

Controversial and outspoken at home and abroad, Olof Palme was by then in his second term as leader of his country. But he still insisted on living as normal a life as he could, and - as on that night - he often dismissed his police protection.

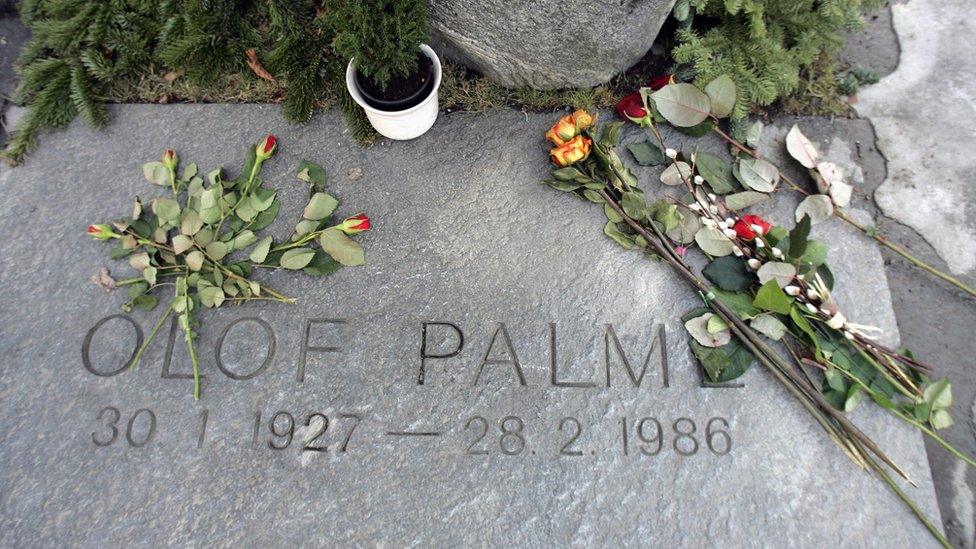

Walking home just before midnight with his wife Lisbet, the prime minister was shot in the back at point blank range. He was dead before he hit the ground.

No killer has ever been found, even though the assassination took place on Sweden's busiest road, and more than a dozen witnesses saw the tall man fire the shots before fleeing the scene.

Now, more than 34 years later, Sweden's Prosecutor's Office has announced it will present the conclusions of its criminal investigation in a press conference scheduled for Wednesday morning.

"I am optimistic about being able to present what happened with the murder and who is responsible for it," Chief Prosecutor Krister Petersson told Swedish public television in February.

The assassination shocked Sweden, and spawned countless conspiracy theories

It is not known if anyone will be charged, or if a new suspect will be named. But there is hope the police may finally be close to solving a murder that has haunted the country for decades, and spawned countless conspiracy theories.

"It's like if they murdered Margaret Thatcher at Piccadilly Circus - just gunned her down - and then the killer disappeared down into the Tube without ever being found," Dr Jan Bondeson, author of Blood on the Snow: The Killing of Olof Palme, told the BBC.

Marten Palme, Olof's son and one of the last people to see him alive, said earlier this year that police "have evidence they do not yet want to disclose".

He thought it might be to do with the murder weapon, which has never been found. "If someone knows something important and has not come forward, it is obviously time to do it," he told Sweden's Aftonbladet newspaper.

Who was Olof Palme?

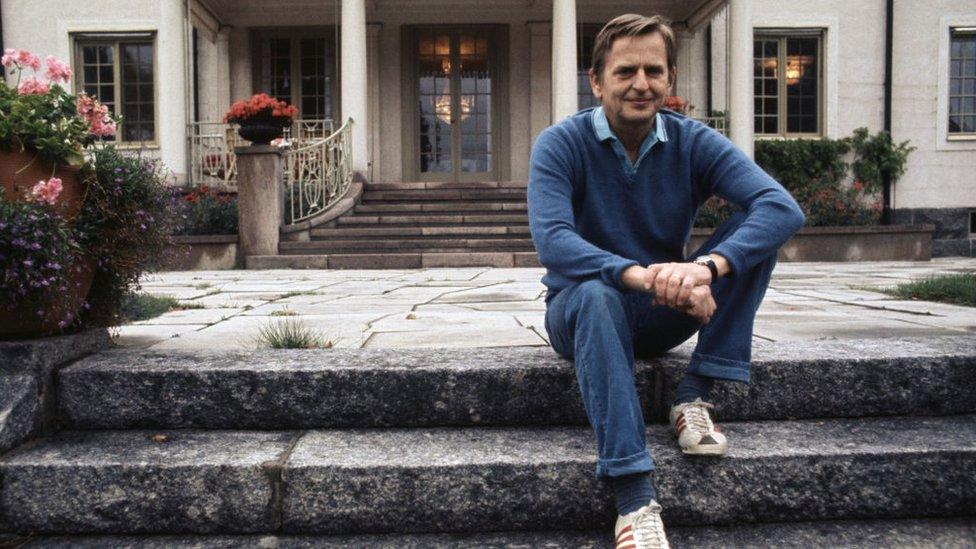

Born in 1927 to an upper class family with aristocratic connections, Palme joined the Social Democratic party in 1949 and rose to lead the party - and Sweden - in 1969, succeeding his mentor Tage Erlander.

"Palme is said to be one of Erlander's boys," Anna Sundstrom, Secretary General of the Olof Palme International Center, told the BBC. "He was sort of raised as a politician by Tage Erlander, who is one of the fathers of the Swedish welfare system. I would say he took and advanced Erlander's policies."

Olof Palme - photographed here with British Prime Minister Harold Wilson - was also well known internationally

During his premiership, Palme increased the power of labour unions, greatly expanded health care and the welfare state, removed all formal political powers from the monarchy and invested heavily in education. Ms Sundstrom said one of the vital reforms was the creation of nurseries and pre-schools, allowing women to enter the work force for the first time and advancing gender equality in Sweden.

He was also a powerful voice in international affairs, criticising both the US and the Soviet Union. Palme passionately opposed the USSR's invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, and in 1972 compared US bombing of North Vietnam with Nazi concentration camps during World War Two - prompting a brief freeze in relations between Washington and Stockholm.

"I don't regret it because in this world you have to speak out fairly loud to make anyone listen," he told the New York Times in 1973, external. "I can't keep silent on this issue and won't be pressurised into silence."

He called the racist apartheid order in South Africa "a particularly gruesome system" and funded the African National Congress, denounced Gen Franco's fascist regime in Spain as "goddamn murderers", and campaigned against the proliferation of nuclear weapons. Palme also served as a mediator during the Iran-Iraq War in the 1980s.

His actions at home and abroad won him as many enemies as supporters. Business owners and liberals in Sweden were enraged by his reforms, while his loud and frequent criticisms of foreign governments infuriated leaders around the globe.

Olof Palme was an outspoken critic of foreign leaders and regimes

"It was almost as if you either loved or hated him," Ms Sundstrom said. "There was a very, very strong resentment, not least on the right of politics. Nowadays when we talk about the strong rhetoric on social media against politicians, all of that we already saw in Sweden during Palme's era. They went after him extremely hard."

"But also he was very well respected and loved in a big segment of the Swedish population," she said. People still come to lay flowers at the site where Palme died.

How did he die?

On the night of the murder - 28 February 1986 - Palme had already dismissed his guards when he got home and his wife suggested an impromptu cinema trip. Lisbet had spoken with their son Marten, who had bought tickets for a comedy film for himself and his girlfriend.

Mr and Mrs Palme left their flat unaccompanied, took the subway from the old town to the centre and met their son and his partner outside the Grand Cinema at about 21:00.

Olof Palme married his wife Lisbet in 1956

The couples parted after the film, and Palme set off with Lisbet down Sveavagen - known as Sweden's busiest road. At the corner of Sveavagen and Tunnelgatan at 23:21, a tall man came up behind Palme and fired two shots - one directly into the prime minister's back at point-blank range, and the other at Lisbet.

The killer then jogged down the road, climbed some stairs to an adjacent street, and disappeared.

Sweden was stunned. Charlotta Wallsten was just 12 years old at the time, but remembers her father telling her that something terrible had happened when she woke up.

"We put on the TV and it was all about his assassination on an open street," she told the BBC. "The whole country was in shock."

Ms Wallsten remembers her school lighting a candle for Palme at a school assembly. "When he was murdered, the politics that you had weren't the most important thing... It was just shock. This didn't happen in Sweden."

Mourners crossed police tape to place flowers, sullying the crime scene

Police seemed also to be in a state of shock. Officers did not properly cordon off the crime scene, and shut down too small an area of the city centre in the hours after the killer fled.

Mourners went past the cordon to place flowers, walking where Palme's blood was still pooled on the ground. Witnesses were able to leave before they could be questioned. One of the bullets was not discovered until days later by a passerby.

Who could have killed him?

Despite the large number of witnesses, police had few leads.

The recovered bullets indicated the killer had used a .357 Magnum handgun - a "very powerful weapon," Dr Bondeson explained. "Even if he had worn a bulletproof vest he would have died. So the murder was done by someone who really wanted to kill him. It wasn't opportune, it was all planned."

The first chief investigator into the case pursued the idea that the Kurdish militant PKK had something to do with his murder. They were fighting a guerrilla campaign against Turkey and had recently been declared a terrorist group by Palme's government.

But he was forced to resign in disgrace in 1987 after a raid on a bookshop - which served as a base for the organisation - garnered zero evidence about the murder.

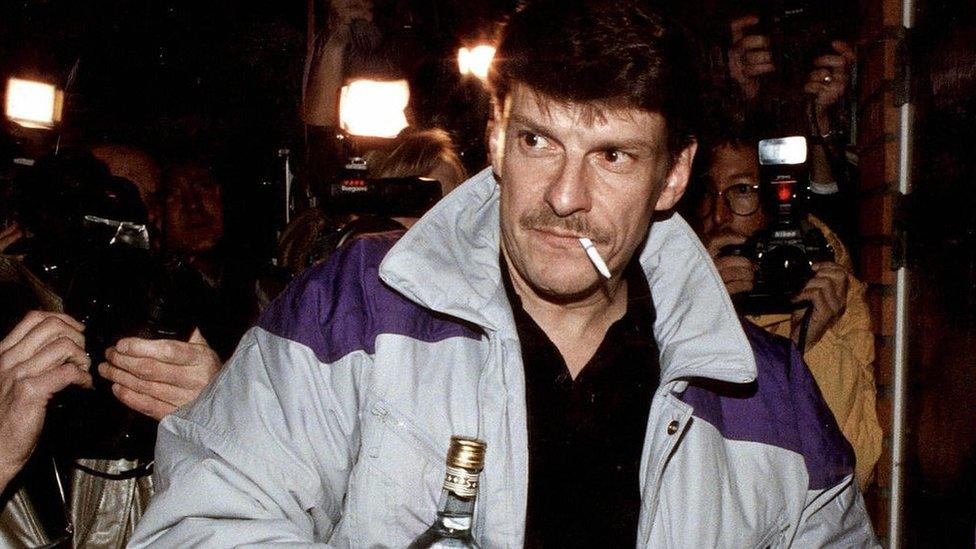

In 1988 police arrested convicted criminal Christer Pettersson. He had killed a man on a Stockholm street with a bayonet in 1970 for seemingly no reason, and he matched the description of a person seen acting suspiciously near the cinema on the night Palme was killed.

During a police line-up, Lisbet Palme identified Pettersson as the murderer. He was convicted and sentenced to life in prison in 1989.

But his lawyer immediately appealed. Without motive or a murder weapon, the courts released him after just three months of his life sentence, and awarded him about $50,000 in compensation. Pettersson died in 2004 a free man.

A famous photo of Pettersson carrying bottles of vodka and Bailey's Irish cream after the Supreme Court rejected a retrial

Sweden's collective trauma and obsession with the assassination has spawned dozens of theories and even a term for the fixation - Palmes sjukdom, or Palme sickness.

A former South African police officer claimed in 1996 Palme was killed because of his stance against apartheid and for funding the ANC. Swedish investigators travelled there that year but could not find evidence to back up the claim, although some believe the old apartheid regime should still be considered a suspect.

Stieg Larsson, author of Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, spent years researching the murder and advanced this theory before his death in 2004.

Dr Bondeson, meanwhile, believes the murder was linked to arms deals with India. Swedish arms company Bofors had a deal to supply India with artillery in the 1980s and 1990s, but it was later revealed the company had bribed several middlemen in India for the contract - a scandal that implicated Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi.

"It may well be that Palme found out that the Bofors company was corrupt the very day of the murder," he said. "That gives the middlemen behind the Bofors deal a strong reason to murder him. But that's something the police have always ignored."

Another possible lead is the so-called Skandia Man. Stig Engstrom - an employee at Skandia insurance company, headquartered near to the murder scene - was one of about 20 people to witness the assassination. He killed himself in 2000.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Police reportedly began investigating Engstrom in 2018. A 12-year investigation by Swedish journalist Thomas Pettersson first identified him as a suspect, alleging he had had weapons training, external and was friends with a man who owned a gun collection and had a fascination with Magnum revolvers.

He was also shown to have lied about his time at the murder scene - claiming he tried to resuscitate the prime minister, which he had not.

"Many Swedes believe that Engstrom will be used as a scapegoat," Dr Bondeson said. "But he was a very short and insignificant looking person, whereas the murderer was tall and strong. And he never killed anybody before or after."

Ultimately, Dr Bondeson does not believe much will come of the announcement. "I think it will end up as a damp squib! But we will see."

"I don't expect anything, I don't expect clarity," Ms Sundstrom said. "But I think anyhow that it's important to close the case. You need in a way closure even though you don't have an answer."

- Published16 November 2016

- Published26 August 2018

- Published17 December 2015

- Published9 May 2012