Coronavirus: EU considers barring Americans from travel list

- Published

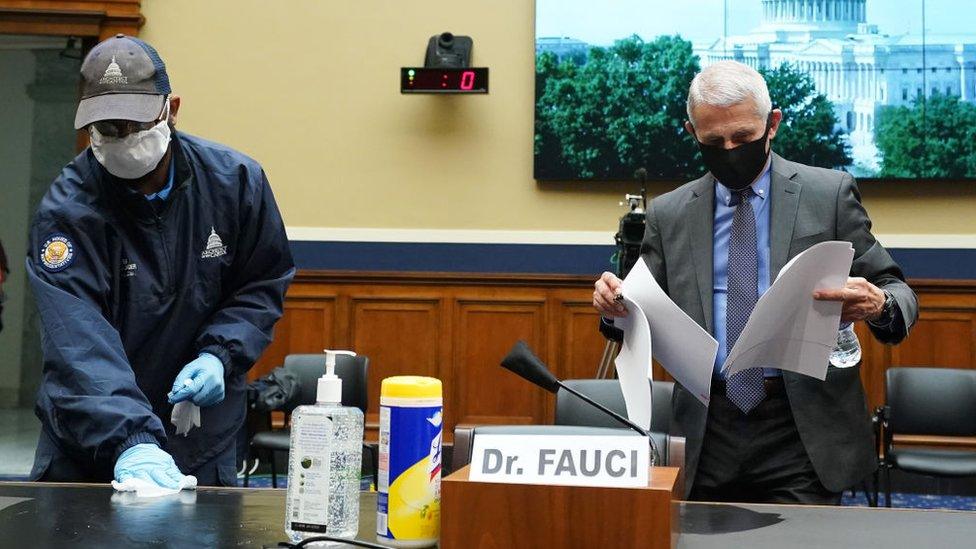

Europe's internal borders began reopening to travellers on 15 June

EU ambassadors are to continue talks on Friday to plan reopening external borders on 1 July, and travellers from the US could be among those not allowed in.

Some European countries are keen to open up to tourists but others are wary of the continued spread of the virus.

On Wednesday US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said he expected a solution "in the coming weeks".

The virus is spreading in the US, so it is likely Americans would be barred.

The 27-member bloc must first agree the measures that non-EU countries should meet before deciding on a safe list.

Brazil, Russia and other countries with high infection rates would also be left off a safe list, according to reports from Brussels.

The EU is not yet thought to have agreed how they will assess which countries meet health standards - one of the criteria for entry. Part of the problem is assessing reliable health data, reports say.

What did Pompeo say?

Travel has largely been banned between the US and EU during the pandemic, but Mr Pompeo said he was "very confident" a solution could be found.

"We certainly don't want to reopen in a way that jeopardises the United States from people travelling here and we certainly don't want to cause problems anyplace else," he said.

He did not give details, but added that the US was working "to get the global travel back in place".

Comparing infection rates with other countries

Latest figures from the EU's health agency, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, highlight Brazil, Peru, Chile, Panama and Saudi Arabia as countries with the highest "case notification rate".

Russia and the US have a lower rate of cases per 100,000 inhabitants but are still higher than most of Europe. The US has seen 2.3 million infections and 120,000 deaths and cases are climbing in several states.

The European Commission is advising ambassadors only to consider countries that are comparable or better than the EU average, external when it comes to new infections, the trend in new infections, as well as testing and tracing.

Reports said member states were assessing two different lists. The Politico website said one covered countries with fewer than 16 cases per 100,000 people and the other with up to 20 cases, which would include Canada and Turkey. The New York Times said the list would be revised every two weeks, so the US could be added later.

Other criteria also being considered are reciprocity and links to the EU. France wants the EU to give access only when it is reciprocated by other countries, while Spain is said to be keen to reopen the border with neighbouring Morocco.

Earlier this month the European Commission also stressed that reopening borders with non-EU states in the Western Balkans was a priority from 1 July. However, EU member Croatia announced on Wednesday that travellers from Bosnia, Serbia, Kosovo and North Macedonia would all face 14-day self-isolation from the end of the day, because of an increase in infections.

The US may also be a problem diplomatically, as on 14 March President Donald Trump unilaterally closed US borders to countries in the EU's Schengen border-free zone. The EU condemned the move at the time.

Why this is a fraught decision for EU countries

Which countries' travellers are allowed in, and which are not?

At first this may seem a practical decision for the EU: if a country outside the EU and Schengen area has high rates of infection, its citizens won't be allowed in to the bloc.

If infection rates are similar to or lower than the EU average, then willkommen, bienvenue, welcome!

Except it's not that simple.

Producing a list of outside countries "acceptable" for EU travel is also a political - and economic - decision.

Tourists bring much-needed revenue to Covid-19-ravaged economies, of course. But EU leaders are not keen to take risks. Even countries wanting an economic boost are aware the political backlash would be huge if tourists bring Covid-19 with them.

And, as is so often the case, opinion between the EU's 27 countries is divided.

France is keen on barring nationals from countries that bar EU citizens

Some worry that barring a particular country over Covid-19 could cause political friction with allies or worsen existing tensions. EU relations with Washington and with Moscow are already delicate, shall we say.

Then there's the issue of reciprocity.

France is particularly attached to this. In other words, if a country bars entry to tourists from an EU or Schengen nation, then that country should be allowed to return the "favour", thinks Paris. Also, if a non-EU country grants access to EU visitors, should the EU be diplomatically obliged to respond in kind?

I'm told the list of outside countries whose citizens will have access to EU/Schengen as of 1 July is likely to be "small" to start with.

Discussions between member states' ambassadors to Brussels are due to continue on Friday, with an outcome to be decided unanimously on Friday or "shortly after".

Can Europe save its tourist season?

The EU is split into two groups that include those hoping to salvage something from this year's summer tourist season and those that fear for the health situation.

Although the EU urged the 27 member states to reopen internal borders from 15 June, several countries have moved carefully to avoid a second spike in infections.

As the coronavirus restrictions ease, countries across Europe have started reopening their borders

Denmark, which was among the first European countries to start lifting its lockdown, has begun reopening its borders more slowly than others. Denmark is a Schengen state but it still has strict criteria for those visiting the country.

Tourists were allowed to return from mid-June from Norway, Iceland and Germany, but not from neighbouring Sweden.

Greece, meanwhile, opened its borders to much of Europe on 15 June in a bid to kick-start its tourist season. Visitors from some countries including Spain, Sweden and the Netherlands face compulsory testing for Covid-19.

- Published2 July 2020

- Published24 June 2020