Duda vs Trzaskowski: The fight for Poland's future

- Published

Andrzej Duda (L) is facing Warsaw Mayor Rafal Trzaskowski

Poland's presidential election on Sunday will be crucial in shaping the country's future and its strained relations with the EU for at least the next three years and perhaps beyond.

Why run-off presents Poles with clear choice

If the incumbent President Andrzej Duda is re-elected for another five-year term, his allies, the nationalist Law and Justice-led government will continue their socially conservative policies, efforts to control independent institutions and generous state handout programme.

If the more liberal mayor of Warsaw, Rafal Trzaskowski, wins, he has said he will stand up for minorities and use the president's right to veto legislation to block what he sees as the government's attempts to politicise the judiciary and attack democratic values.

Mr Trzaskowski says he will co-operate with the government but a victory for him would almost certainly start a war between the two branches of power.

Both men have distinct visions for the future of Poland.

What does Andrzej Duda believe?

President Duda, 48, is a lawyer by training. He won a surprising victory in 2015 representing the young, moderate face of the Law and Justice party, which had lost a string of elections under all powerful party leader and candidate, Jaroslaw Kaczynski.

He is a socially conservative Roman Catholic, who says he wants to defend the traditional family model.

The socially conservative Mr Duda has a lot of support in small towns and villages

On the one hand, he supports the government's popular and generous welfare scheme, symbolised by the 500+ programme, under which families receive 500 zloty (£100; €110; $125) per month for each child until the age of 18.

Many Polish families have been lifted out of poverty as a result of the government's policies, and, for the first time since the end of communism in 1989, feel there is a party that cares about their needs.

This is especially true in villages and small towns, where President Duda won an absolute majority of votes in the first round of the election two weeks ago.

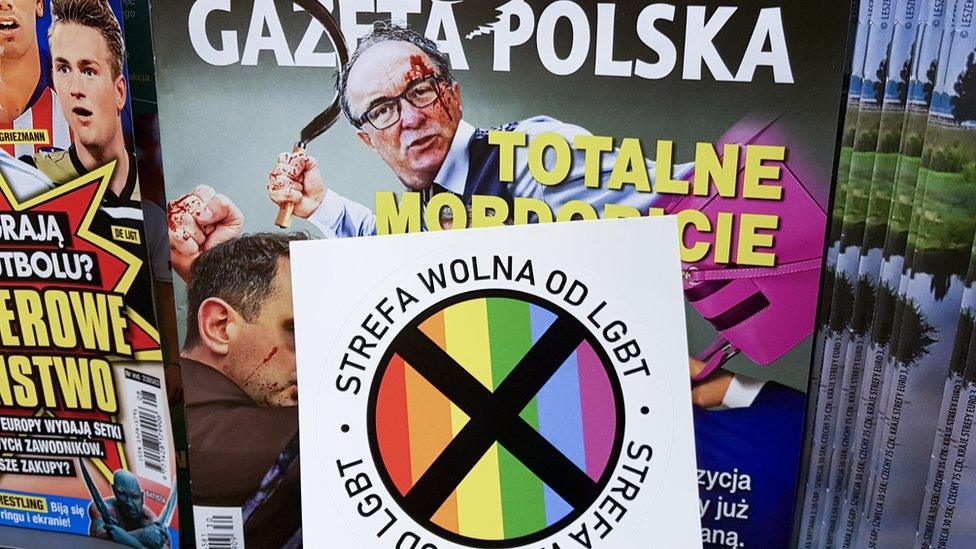

On the other hand, he has vowed to protect Polish families from what he calls an imported "LGBT ideology" that is aggressively trying to sexualise Polish children.

Poland has been called the worst country in the EU for LGBT rights

In practice, sex education classes in Polish state schools do not exist.

Instead students have more wide-ranging "family life education" classes, which may include sex education, often led by priests or nuns.

President Duda is also a supporter of the government's legislative changes to take greater control over independent institutions, most prominently the public media and judiciary.

Presidential adviser Andrzej Zybertowicz says Mr Duda is opposed to discrimination

Poland's public broadcaster, Polish TV, is funded by the taxpayer and is bound by its charter to present balanced coverage of political events.

Instead, its main evening news bulletin praises the government and Mr Duda daily and attacks Mr Trzaskowski, accusing him of being in cahoots with Jewish and LGBT interest groups.

Mr Duda supports greater government control over the media

Mr Duda has also strongly backed most of the government's changes to the judiciary that the EU and multiple international organisations say have undermined its independence and the rule of law.

Relations with the EU have been strained as a result and Mr Duda once called it an "imaginary community from which we don't gain much".

Under the current budget, Poland is the biggest net recipient of EU funds.

What about Rafal Trzaskowski?

Mr Trzaskowski, also 48, is a deputy leader of Poland's centre-right Civic Platform party, which governed Poland between 2007-2015, mostly under Donald Tusk before he was elected to head the European Council.

His party has always performed best in large metropolitan cities.

Mr Trzaskowski is pro-EU and has support in Poland's major cities

In the first round, he won 30.46% of the vote to Mr Duda's 43.5%, scoring his biggest victory in the affluent Warsaw district of Wilanow.

In an interview with the BBC, Mr Trzaskowski acknowledged that some members of the government he was a minister in had at times been a "bit patronising" towards voters.

Although he's economically liberal, he said Law and Justice had correctly identified income inequality as a problem that needed to be addressed with programmes like 500+, a policy he says he supports.

He represents the more liberal wing of the party, and, as Warsaw mayor, has taken part in LGBTQ Equality marches and proposed introducing classes in the capital's schools to counteract bullying against minorities.

However, he said recently he opposed the adoption of children by same sex couples, which most Poles do according to surveys, after President Duda tabled an amendment to the country's constitution to expressly forbid it.

Polish democracy is 'under attack'

As president, Mr Trzaskowski's power would mostly be limited to vetoing legislation as any bills he presents himself could be rejected by the governing camp's majority in parliament.

He told the BBC that Poland was still democratic but its "democracy is under attack" as the government was politicising independent institutions, such as the judiciary, and trying to strip local government of its powers.

He said he would veto further attempts to politicise the courts and propose making the office of prosecutor general independent once again.

Under the current government the justice minister is also prosecutor general, giving him extraordinary power over the conduct of prosecutions.

As a former Europe minister, Mr Trzaskowski says he wants Poland to take a more active role in the EU negotiations.

He worries that once the financial benefit of membership is reduced in future, the current government's antipathy to some aspects of the European project could eventually lead to Poland leaving the EU.

- Published10 July 2020

- Published29 June 2020

- Published28 June 2020

- Published14 June 2020

- Published19 May 2020

- Published7 May 2020

- Published17 December 2019

- Published1 December 2019

- Published8 October 2019

- Published25 July 2019