Belarus on the brink: What now?

- Published

The Minsk Tractor Factory, once a Lukashenko stronghold, has turned against him

Standing outside the giant truck-making factory BelAZ, it feels like the time of the 1917 Russian Bolshevik revolution. People pass leaflets to workers through the metal bars of the factory fence. Workers organise "stachkomy" - strike committees - and "comrades" give passionate speeches inside factories calling on their colleagues to join a "zabastovka" - a strike.

These strikes became a major boost to the opposition movement in Belarus as thousands of people went on to the streets to voice their protest against what they see as rigged elections. But as workers walk off the job to show their support for protesters, many now are asking what will be next for them and for Belarus.

Opposition leaders are trying to come up with a plan. They have set up a co-ordination council to discuss what to do next. However, at a press conference late on Tuesday, they spent much of their time denying President Alexander Lukashenko's accusation that they were trying to seize power.

Next steps

"We use only legal ways, legal and non-violent methods," said Olga Kovalkova from opposition candidate Svetlana Tikhanovskaya's team, at the start of her speech. "All members of the council acknowledge that mass violations took place during the election campaign and the vote counting, they do not recognise the official results of the election. They regard the violence used by police force as criminal and demand to release all political prisoners."

The members of the consultation council avoided giving direct answers when they were repeatedly asked about possible steps they could consider in order to move forward.

Read more on the Belarus crisis:

This lack of clarity about what to do next could seriously undermine the opposition movement. Already there are signs suggesting that the momentum for factory strikes could be winding down. According to Sergey Dylevskiy who represents strikers at the giant Minsk tractor plant (MTZ), about 20% of workers at the plant are on strike. The rest are too afraid to leave their jobs and support the movement, he said.

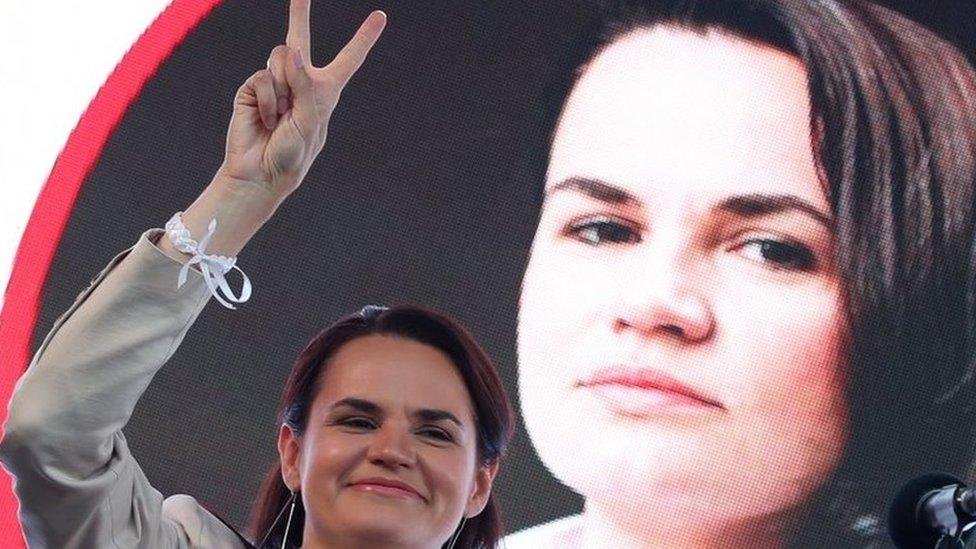

President Lukashenko and opposition candidate Svetlana Tikhanovskaya give very different messages

Many workers are facing pressure from their employers. "They're worried that they would lose their bonuses and salaries," said Sergey Korovach, a miller at MAZ - the Minsk Automobile Plant that makes heavy trucks and buses. "They're worried that they might lose their jobs."

Mr Korovach says that only a small fraction of over 10,000 MAZ workers went on strike on Tuesday. He says that many workers became discouraged by the low turnout and now preferred not to take a risk.

According to the independent tut.by news network, factory workers are getting letters from ministries informing them of possible punishment for their action. "Participating in a strike or meetings that are organised without following labour legislation violates labour disciplines and this entails full responsibility," the letter reads.

In search of a leader

"We're witnessing a unique situation when protests are decentralised and spontaneous," said Maria Kolesnikova, a prominent opposition figure. "I wouldn't say that in order to continue the protests, we must have a leader."

But without a clear leader, it is uncertain whether the opposition can mobilise the crowd.

Opposition candidate Svetlana Tikhanovskaya was forced to leave Belarus right after the vote. Her colleagues say that they expect her to be back soon and her return could inject fresh energy into the protest mood and create a character for people to rally behind.

During a meeting with the workers at the MTZ factory on Monday, for the first time since the protests started, President Lukashenko indicated a possible scenario of his departure from power.

"You need to adopt a new constitution through a referendum and then have new elections of the president, parliament and local government," he said. "And I will step down according to the constitution." He made it clear he wouldn't do it under the pressure of street protests.

Ukrainian example

But most protesters want the president to leave immediately.

Following the biggest opposition rally in the history of independent Belarus last Sunday, thousands of protesters continue to gather in Minsk's Independence Square during the evening. People in festive mood wave opposition flags and chant "Thank you" to those who joined the movement.

Children have also been among the protesters, with slogans such as "Give freedom to live"

On the surface it may look as if the protests may have reached a plateau. And yet large crowds are expected to gather at weekends. People's anger at the violence and abuse used by authorities against protesters is not going away anytime soon. It is this feeling that is fuelling these rallies.

Many here compare what's happening in Belarus to neighbouring Ukraine's "Maidan" - the mass protests that ousted President Viktor Yanukovich in 2014. It took several months for the protests to build up there and some suggest that this could be a path that Belarus may follow. But even the opposition says that they don't want to have a Maidan because in Belarus it's largely associated with unrest and disturbances.

People here bring their families to the streets and carry balloons and flowers in order to show that their movement is peaceful. But in Ukraine too the demonstrations were peaceful until authorities used force to disperse the protesters.

- Published17 August 2020

- Published8 September 2020

- Published15 August 2020

- Published1 August 2020

- Published17 August 2020