What's happening in Belarus?

- Published

"We want a new president!" Tens of thousands of protesters took to the streets of Minsk

Belarus is gripped by mass protests, triggered by an election widely believed to have been rigged in favour of the long-time leader Alexander Lukashenko.

The scale of the protests is unprecedented for Belarus. More than 100,000 have packed into central Minsk, the capital, for four consecutive Sundays since the disputed 9 August election.

More than 600 people were detained during the 6 September protests - in Minsk and some other towns and cities. Rallies for Mr Lukashenko have been much smaller.

After violent clashes with opposition demonstrators, numerous allegations of police brutality, processions of women in white with roses and walkouts at major state enterprises, we take a look at how all this came about.

Sergiy says riot police in Belarus threatened to burn him alive

What is the background?

Europe's longest-serving ruler, President Lukashenko took office in 1994 amid the chaos caused by the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Often described as Europe's "last dictator", he has tried to preserve elements of Soviet communism. Much of manufacturing has remained under state control, and main media channels have been loyal to the government. The powerful secret police is even still called the KGB.

At the same time, Mr Lukashenko has tried to style himself as a tough nationalist with a direct manner, defending his country from harmful foreign influences, and a guarantor of stability.

These factors have given him - until now - a solid base of support, though elections under his rule have never been considered free or fair.

The opposition protests have been fuelled by complaints about widespread corruption and poverty, a lack of opportunities and low pay. Dissatisfaction was compounded by the coronavirus crisis.

Belarus: The basics

Where is Belarus? It has Russia - its former imperial master - to the east and Ukraine to the south. To the north and west lie EU and Nato members Latvia, Lithuania and Poland.

Why does it matter? Like Ukraine, this nation of 9.5 million is caught in rivalry between the West and Russia. President Lukashenko, an ally of Russia, has been nicknamed "Europe's last dictator". He has been in power for 26 years, keeping much of the economy in state hands, and using censorship and police crackdowns against opponents.

What's going on there? Now there is a huge opposition movement, demanding new, democratic leadership and economic reform. They say Mr Lukashenko rigged the 9 August election - officially, he won by a landslide. His supporters say his toughness has kept the country stable.

Opponents consider Mr Lukashenko's bravado about coronavirus - he suggested combating it with vodka, saunas and hard work - to be reckless and a sign that he is out of touch.

Then a crackdown on opponents ahead of the presidential election, with two opposition candidates jailed and another fleeing the country, led to the creation of a powerful coalition of three women closely involved in those campaigns.

What happened in the election?

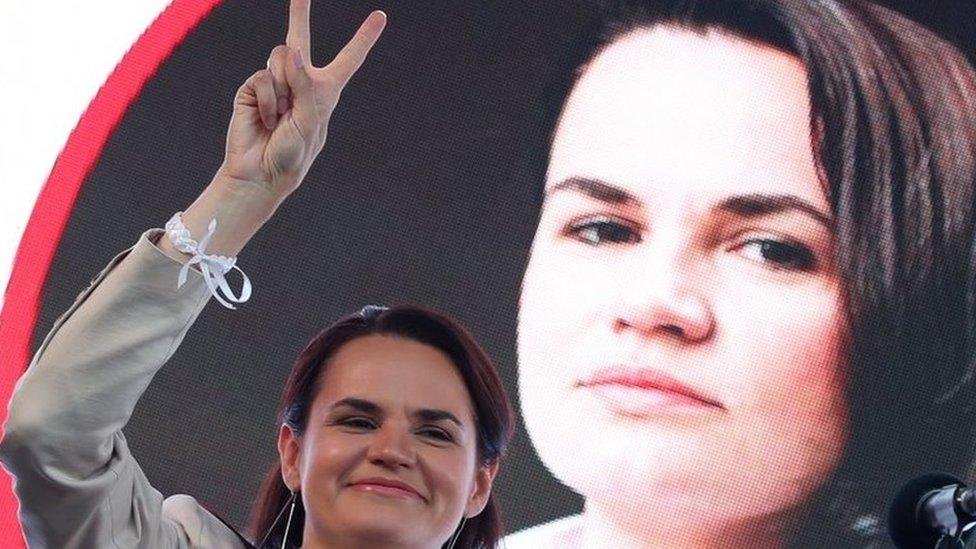

One of the trio, Svetlana Tikhanovskaya, registered as a candidate in place of her arrested husband Sergey Tikhanovsky.

The 37-year-old English teacher and her two allies toured the country, drawing record crowds of people frustrated by the lack of political change.

Voting day arrived amid widespread fears among the opposition about possible fraud. With no independent observers invited, these fears seemed well-founded and numerous apparent irregularities were documented. An internet blackout began which lasted several days.

Alexander Lukashenko has described the opposition as rats

Polling closed and exit polls were released that closely resembled the results that were to be published the next day - suggesting that Mr Lukashenko had won with 80% of the vote. Ms Tikhanovskaya gained only about 10%, they said.

Those results were later rubber-stamped by authorities, but the main opposition candidate insisted that where votes had been properly counted she had polled 60-70%.

Disbelief and anger at what appeared to be quite brazen tampering with the results quickly spilled into the streets.

On the night after the election, violent clashes led to 3,000 arrests in Minsk and other cities. Police fired tear gas, rubber bullets and stun grenades, not seen before in Belarus, to disperse crowds.

Further nights of violence saw thousands of arrests throughout the country.

An ex-elite soldier in Belarus bins his uniform in protest

On the day after the election, Ms Tikhanovskaya tried to complain to election authorities about falsifications of the result. She was detained for seven hours and was forced to leave for Lithuania, where she had earlier sent her children.

In an emotional video address to supporters, she said she had overestimated her own strength and was leaving for the sake of her children.

'Human life is the most precious thing': Svetlana Tikhanovskaya speaks out from exile

Later, she launched a Co-ordination Council to negotiate a transfer of power, made up of civil society activists, lawyers and respected cultural figures.

And in a video address from Lithuania on 17 August, she said she was ready to lead Belarus, pending new fair elections, and urged security officers to switch sides.

She has made several video appeals to the international community - including the UN - for support to force Mr Lukashenko to quit and to help establish democracy in Belarus.

Mr Lukashenko reacted with hostility, refusing any negotiations with the new council. Members of it were detained and questioned.

On 19 August, prosecutors launched a criminal case against the council, accusing the opposition of plotting to seize power.

How have the protests evolved?

During the post-election clashes, details emerged of alleged police brutality, with detainees badly beaten and forced to endure overcrowded jails.

Many sought medical help and posted pictures of their injuries on social media after they were released.

This produced a new wave of demonstrations. Friends and relatives gathered at detention centres demanding news about detainees, and women dressed in white, carrying roses, linked arms and marched through the streets.

A 73-year-old great-grandmother has turned into an unlikely hero for demonstrators in Belarus

At major state-owned enterprises around the country, workers called strikes and joined the protests.

On 17 August, state TV staff walked out, joining the protests against Mr Lukashenko's re-election. Earlier, there were several high-profile resignations there.

Mr Lukashenko was booed by striking workers when he visited a tractor plant.

The authorities are seeking systematically to dismantle the Co-ordination Council.

There is a pattern of forcing opposition leaders to leave Belarus - through intimidation and threats, such as to remove children from their mothers, the opposition claims.

So Ms Tikhanovskaya is now based in Lithuania with her children, while her husband Sergey remains in jail.

Her close ally, Veronika Tsepkalo, is now in Poland with her family. Her husband Valery Tsepkalo, a former ambassador to the US, had been barred from running against Mr Lukashenko, and in late July, had fled to Moscow with their children.

Another leading dissident, Olga Kovalkova, moved to Poland on 5 September.

Ex-banker Viktor Babaryko tried to run against Mr Lukashenko but was barred and remains in jail.

His ally Maria Kolesnikova was confirmed as having been arrested on 8 September. The border police said she had tried to enter Ukraine in a speeding car with two fellow council members, Anton Rodnenkov and Ivan Kravtsov, who carried on into Ukraine.

The opposition says the border incident with Ms Kolesnikova was staged by the authorities, to suggest that the opposition were cowards fleeing the country.

- Published23 August 2020

- Published16 August 2020

- Published15 August 2020

- Published14 August 2020

- Published11 August 2020

- Published13 August 2020

- Published1 August 2020