The Eastern Mediterranean tinderbox: Why Greek-Turkish rivalries have expanded

- Published

Turkish drilling vessel Yavuz is escorted by a Turkish Navy frigate in the Eastern Mediterranean

Over recent weeks, tensions have been rising in the waters of the Eastern Mediterranean, prompted by what seems like a simple rivalry over energy resources.

Turkey has pursued an aggressive gas exploration effort, its research vessel heavily protected by warships of the Turkish Navy. There have been encounters with rival Greek vessels and a third Nato country, France, has become involved, siding with the Greeks.

Most recently it's been announced that a small number of F-16 warplanes from the United Arab Emirates (UAE) are deploying to an air base on Crete for exercises with their Greek counterparts. Ostensibly this is a routine deployment.

So what is going on here? Are the tensions just about gas resources? Why are seemingly far-flung countries being drawn in? And just what risk is there of the Eastern Mediterranean turning into a worsening geo-political tinderbox?

What's happening is dangerous, complicated and threatens to exacerbate existing fault lines in the region.

A more assertive Turkey

While gas exploration is the immediate cause, the roots of the problem lie much deeper. What you have is a long-standing conflict between Greece and Turkey being revived in a new context.

Grafted on to this, you have a regional or geo-strategic rivalry that pits a much more assertive Turkey against several other players. The battleground for this struggle extends from Libya across the waters of the Eastern Mediterranean to Syria and beyond.

The tensions are real and growing. One concern is that as countries coalesce in their opposition to Ankara's regional ambitions, Turkey itself feels more isolated. This risks it becoming ever more assertive.

The Eastern Mediterranean tensions also highlight another shift in the region - the decline of US power or, perhaps more accurately, the decline of the Trump administration's strategic interest in what goes on there.

President Donald Trump has suspended Turkey from the F-35 warplane programme after its purchase of advanced Russian surface-to-air missiles. But there has not been any real consistent US pressure on Turkey to match the trouble that it has been creating for US policy within Nato, in Syria and elsewhere.

In the absence of clear US action, Germany has sought to mediate between Greece and Turkey, with France weighing in more explicitly on the side of the Greeks.

So let's take the areas of tension one by one:

Energy

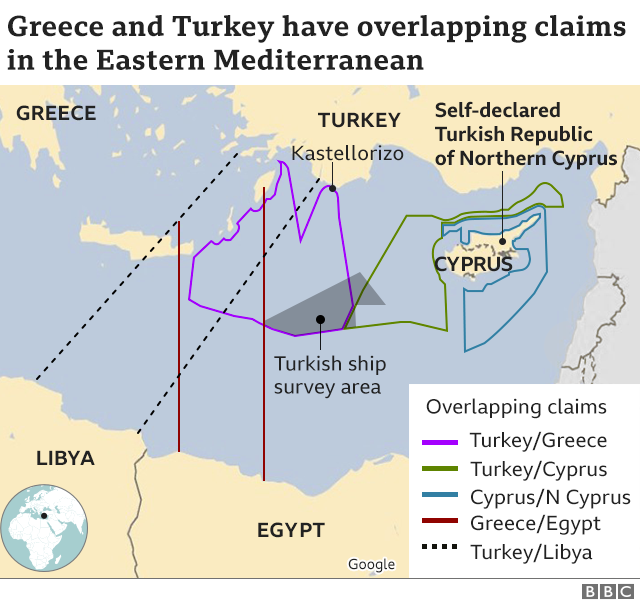

At one level it's all about gas. Several countries in the region have either found significant gas fields or are actively exploring to find them. This can have very mixed consequences. On the one hand it super-charges national rivalries, with ongoing battles over the delineation of maritime boundaries, who owns which plot of undersea territory and so on.

Indeed, deals to recognise respective rights have prompted upticks in tension. Last year, Turkey signed a maritime accord with the Libyan Government of National Accord (GNA) and set about renewed gas exploration in areas that Greece regards as its economic zone.

A drilling vessel in the Bosphorus on the way to the Mediterranean to explore

Tensions ensued. Earlier this month, Greece and Egypt signed a maritime boundary agreement, prompting Turkish anger, a renewed exploration effort and naval deployments.

But the curious thing is that, while energy exploration almost inevitably exacerbates tension and in the longer term could well fuel a regional air and naval arms race, concerted action is going to be needed if the economic benefits of this gas are to be realised.

Pipelines and other vulnerable infrastructure must be created. These must cross several countries' undersea "territory" if they are to make landfall, say, for crucial European markets.

A fledgling international infrastructure is being established for the potential energy producers of the Mediterranean basin and this could ultimately help to reduce tensions, maybe even offering a path to the resolution of the long-standing Cyprus problem as well.

Cyprus

This has been in dispute between Greece and Turkey ever since Turkish forces invaded the island in response to a Greek-backed military coup in 1974, and the subsequent unilateral declaration of a Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus. It builds upon a much longer history of enmity between the Greeks and the Turks going back to before the modern Turkish state was founded.

For more than 40 years Cyprus has been a divided island

Despite multiple diplomatic efforts - there were hopes that as Turkey came ever closer to European Union membership, the Cyprus issue might be easier to resolve - it has proved as intractable as ever.

Now, there is no prospect of Turkey joining the EU. And the tensions over energy have added a new element to a very old dispute.

The 'New Ottomans'

Another crucial element of the puzzle is the much more assertive foreign policy being pursued by Turkey, which some have likened to a resurgence of the old Ottoman Empire. The geographical horizons of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan have certainly expanded.

Turkey's strategic stance has shifted since the end of the Cold War with the demise of the staunchly secular state and a more Islamist tone to its politics.

The ruling AKP party saw a dynamic and growing Turkish economy as helping to establish the nation as a player with regional reach. Recently Turkey's economy may have faltered, but President Erdogan shows no sign of drawing in his horns.

A Turkish seismic research vessel escorted by Turkish Navy ships this month

Indeed the government's Blue Homeland doctrine explicitly envisages a much greater maritime role for Turkey within what it regards as its own strategic waters.

The Turks are often drawn as the villains of the piece and their single-minded pursuit of their own perceived interests has offended friends and foes alike.

But equally Turkey has seen what it perceives as its vital national interests threatened - not least in Syria - where it feels let down by many of its Western Nato allies, the United States among them.

Turkey has sought to steer its own course, engaging with other players like Russia and Iran where necessary. It has, by all evidence, enjoyed this relative measure of strategic autonomy and has sought to expand its regional footprint, weighing in heavily on the side of the GNA government in the Libyan civil war.

Like so many battles in the region - as indeed in Syria - this has become to some extent a proxy war, with various outside players lining up against each other. And in Libya, Turkey is opposed by powerful actors like Egypt and the UAE.

Turkey has intervened heavily on the side of the UN-backed Libyan government while the UAE and Egypt back the eastern militias of Gen Khalifa Haftar. Turkey and the UAE have mounted a kind of proxy drone war in Libya's skies, with the UAE operating its Chinese-supplied drones and the Turks deploying a home-built armed drone of their own. This Turkish air power proved decisive in saving the GNA.

The Libya conflict has also deepened the enmity between Turkey and Egypt. Relations went into the freezer following the overthrow in Egypt of the Muslim Brotherhood - seen as a fraternal regime by the Turks.

Turkey has opposed the forces of Gen Haftar in Libya, forces backed by Egypt

And differences over Libya have soured relations between Turkey and France too. There was a naval stand-off not so long ago where Turkish warships intervened to stop the French Navy from intercepting a cargo vessel thought to be carrying weapons off the Libyan coast.

Amid the growing Greek-Turkish tensions, France despatched two warships and two maritime strike aircraft as a show of solidarity with Athens.

So the immediate cause of tensions in the Mediterranean may be energy-related but this only tells part of the story.

There are both deep-seated and developing diplomatic strains which, combined, could erupt without warning.

If ever a region needed crisis management, then it is the Eastern Mediterranean. But who exactly is to be the manager? And do the parties themselves actually want to be managed?

- Published24 August 2020

- Published25 August 2020

- Published11 January 2017