My search for novelist Rumer Godden's famed French summer

- Published

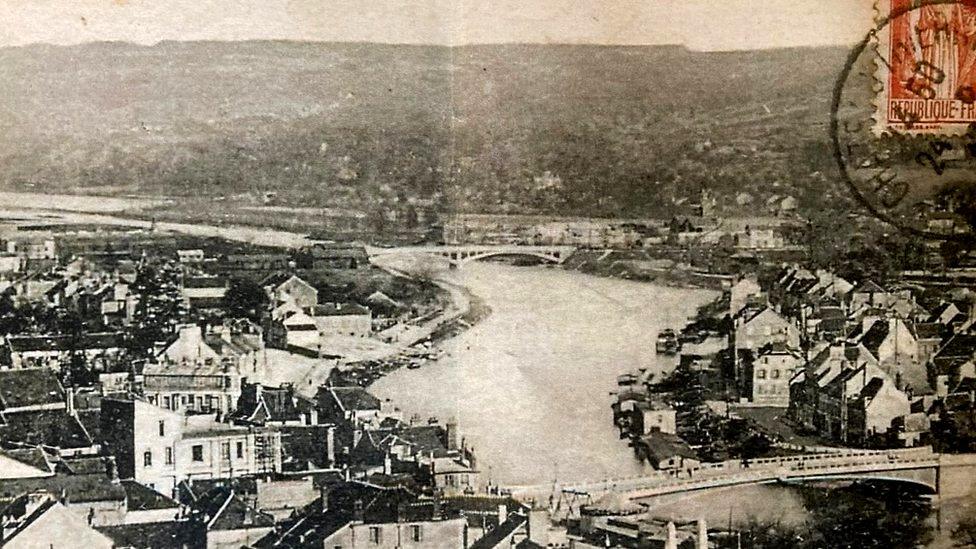

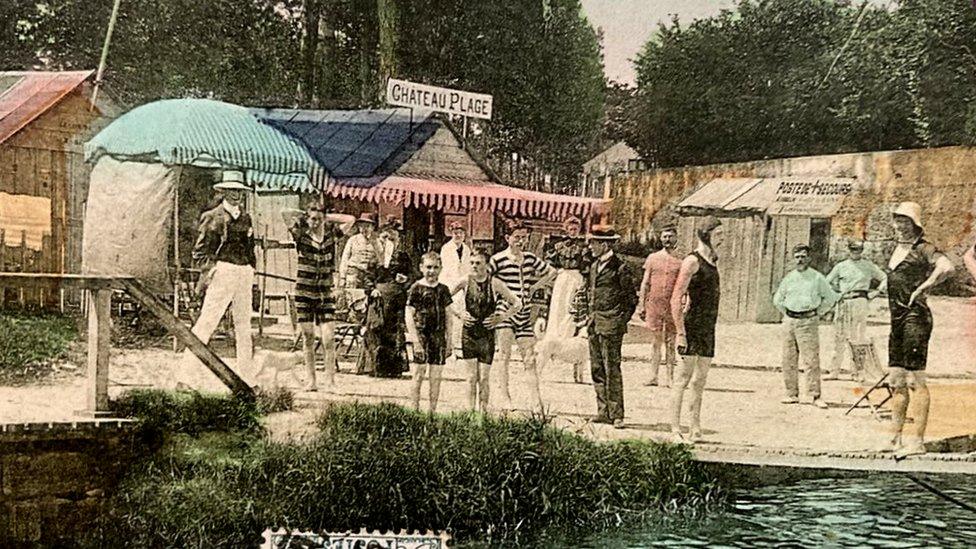

An old postcard view of Château-Thierry

In the summer of 1923 the novelist Rumer Godden, then a girl of 15, came with her mother and three sisters to a hotel in the town of Château-Thierry, near the Great War battlefields of the Marne.

Their mother had grown irritated with the girls' "selfishness" back home in Eastbourne in southern England, and wanted them to learn a lesson in self-sacrifice by contemplating the cemeteries of war dead.

En route to Château-Thierry, however, the mother was taken ill with an infected horse-fly bite. Unable to move from her bed, she left the girls to shift for themselves.

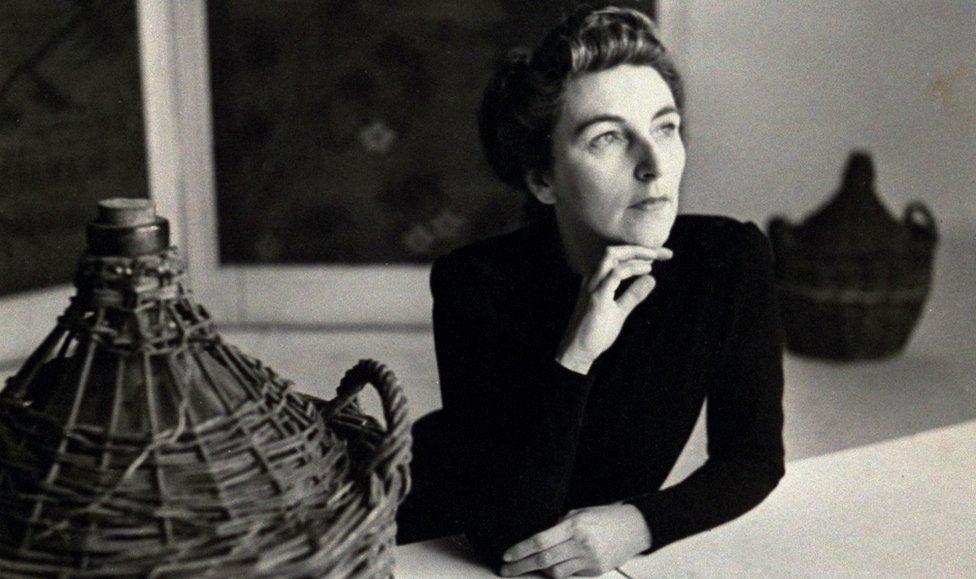

That holiday became immortalised many years later, when Rumer Godden wrote a novel called The Greengage Summer. It is a story of teenage discovery and awakening, set against the alien but alluring backdrop of a town in provincial France.

In an introduction written when she was a very old lady, Rumer Godden said it was all basically true. In the novel the hotel was called Les Oeillets (The Carnations), but in reality, she said, it was the Hôtel des Violettes.

Godden's 1958 novel The Greengage Summer is set in 1920s northern France in the years after World War One

Left to their own devices, the children enjoyed the run of the place throughout that hot, halcyon August.

As in the book, she and her elder sister had their first brushes with sexuality and womanhood. And they became friends with a dashing Englishman who in a dramatic twist turned out later to be a wanted bank-robber.

A fan of The Greengage Summer, as of all Rumer Godden's books, I was on a mission to find what trace I could in the Château-Thierry of today.

Was the hotel still there? And the greengage orchard at the bottom of the garden? And the bathing-place where the Englishman faked his alibi?

And what of him? If - as Rumer Godden said - there had indeed been a raid on the hotel in search of an English crook, would that not be in newspapers of the day?

In 1923, Château-Thierry was re-emerging from the horrors of the war. The American army had been based there and fought hard to stop the Germans' last, desperate 1918 offensive. Much of the town had been wrecked.

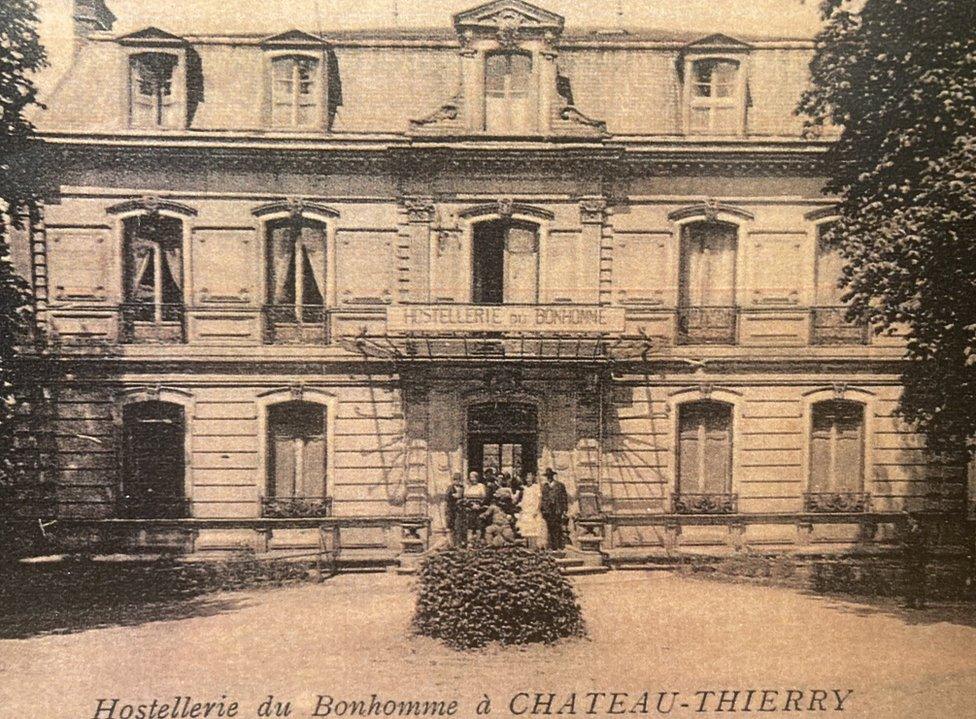

At war's end an Anglo-Irishwoman called Violet Grierson, who had worked on the front with the Red Cross, came to the town. After initially running a tea-room she decided that there were opportunities in tourism, because of the growing numbers of veterans and families who were starting to visit.

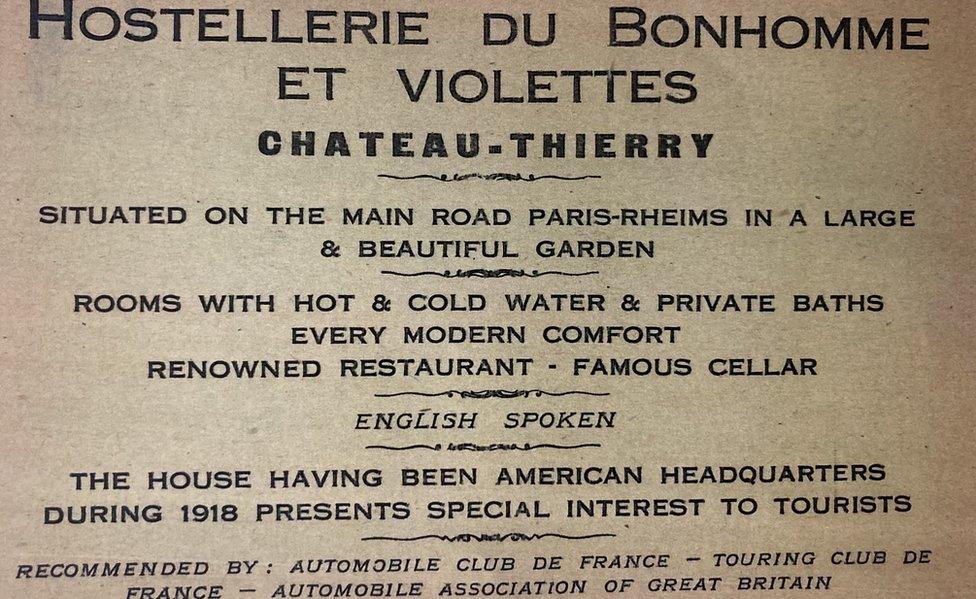

And so in 1920 Grierson opened the Hostellerie du Bonhomme et Violettes, in a grand rambling house on the Avenue de la République not far from the railway station, with a walled garden running down to the Marne.

Despite the slight confusion over the name, there is no doubt that this is the hotel of the book.

In her introduction Rumer Godden said her mother had asked a clergyman for advice on where to stay for a visit of the battlefields, and he had said there was no better place than the Hôtel des Violettes.

We can presume that the hotel, with its English management, was winning a reputation at the time among English and American tourists.

Later - according to an obituary of Violet Grierson in the records of the Château-Thierry historical society - it had such luminaries as Franklin D Roosevelt and Sir Anthony Eden among its guests.

Rumer Godden described what felt to her young self like a château - really a bourgeois family mansion - and its summer smells of "warm dust and cool plaster… Gaston the chef's cooking, furniture polish, damp linen, and always a little of drains".

A terrace gave on to a formal garden, and then beyond that to the greengage orchard, the eating of whose fruit by the narrator is an Eden-like entry into the mysteries of adolescence. And then through a blue door you were by the willows and reeds of the river.

The place is easy enough to identify - but sadly the hotel has long gone. A gendarme barracks replaced the building, but then it too was abandoned. So now there is just tarmac and weeds where once the orchard grew.

But the old wall is still there, and in the wall there is still a gate, and the gate still gives on to the reeds and willows. This is where Rumer Godden (Cecil in the book) came to walk and swim in 1923.

What happened to the hotel is told in another document - a long-forgotten memoir written in 1945 by Violet Grierson's sister, Helen, who lived with her and helped run the business.

On May 19, 1940 they were giving lunch to guests in the dining-room when "we heard the cook running down the stairs and shouting "The Boches, the Boches!"

A bomb fell directly on to the building, killing 16 people.

"An old French officer who was at a table with his wife was untouched, but his wife was dead. Another woman was unharmed, while her husband who was right next to her was killed," remembered Helen Grierson in Château-Thierry under Occupation.

A drawing of the wrecked hotel

They had to abandon the hotel, which was too badly damaged to survive.

When Rumer Godden went back to Château-Thierry in the 1950s, she found the building mouldering behind padlocked gates. But the memories were so poignant she then embarked on writing the novel.

Other recollections from the book are also true to life. She recalls a bar in Château-Thierry called the Giraffe, where the children go with the Englishman. The bar has gone, but local memory has not - because there is still the original emblem of a giraffe emblazoned on the wall.

There is the Hôtel Dieu - the hospital founded in 1304 where in the book their mother was treated by nuns. That is now a museum.

A famous poet she refers to is Jean de la Fontaine, who lived in the town and his best known for his Fables.

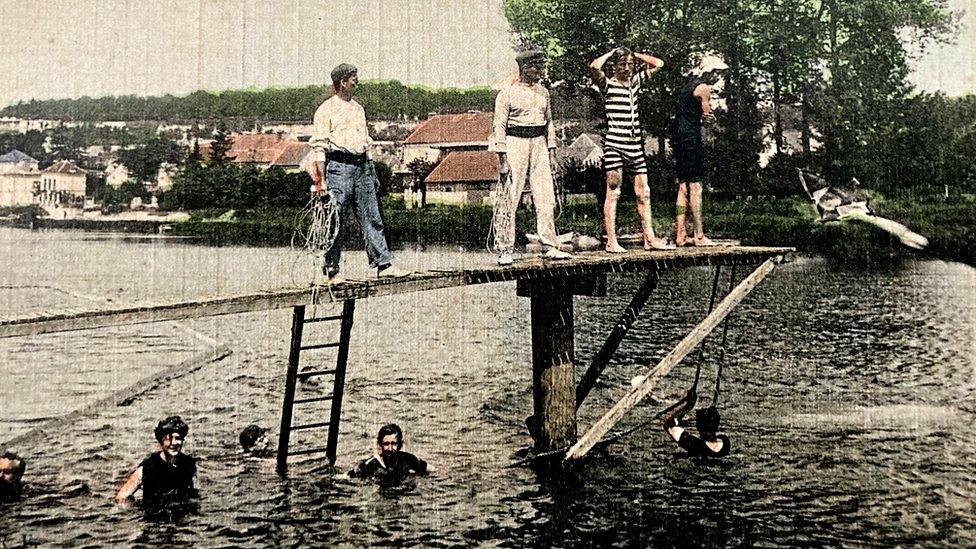

The remains of the municipal bathing-place where the children yearn to go, but don't have the money, can still be seen at the eastern end of the island in the river.

Back in the day it was called Château-Plage and only closed in the 1960s.

The hotel also had a private bathing place, which must have been on the bank nearby.

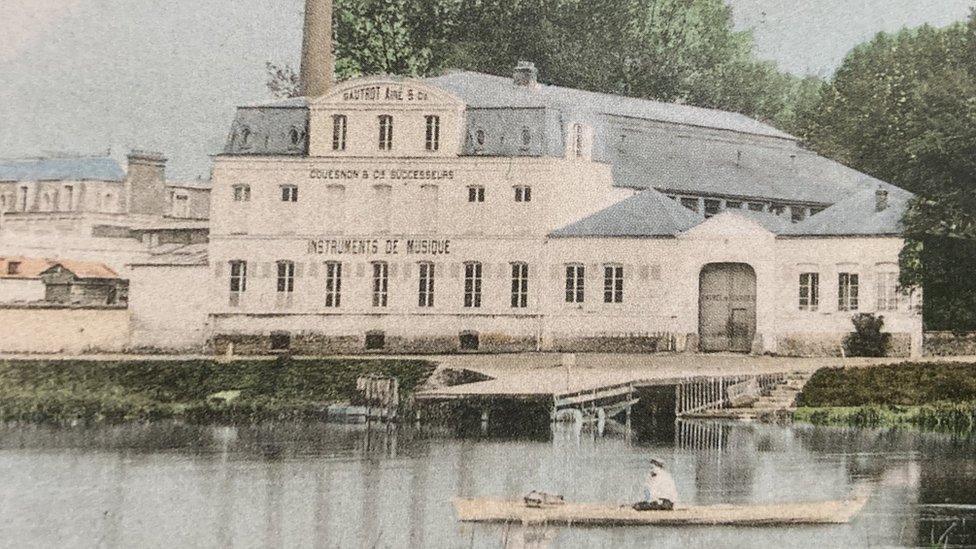

There was also a brass instruments factory, whose whistle in the book sounds out several times a day and whose annual ball in the hotel provides the backdrop to an important episode.

Couesnon trumpets and tubas once employed 600 people in Château-Thierry and were famous throughout the world. You can still buy them online.

But what, finally, of the story's plot-twist? The Englishman?

In the novel he is Monsieur Eliot, lover of the hotel's French manageress, and at the end he escapes up-river on a barge.

In her introduction Rumer Godden remembers him as a Mr Martin, who befriended her and her sisters and drove them around the local countryside.

But then there was the police raid on the hotel and it turned out Mr Martin had decamped. He was, wrote Rumer Godden, a "well-known international thief".

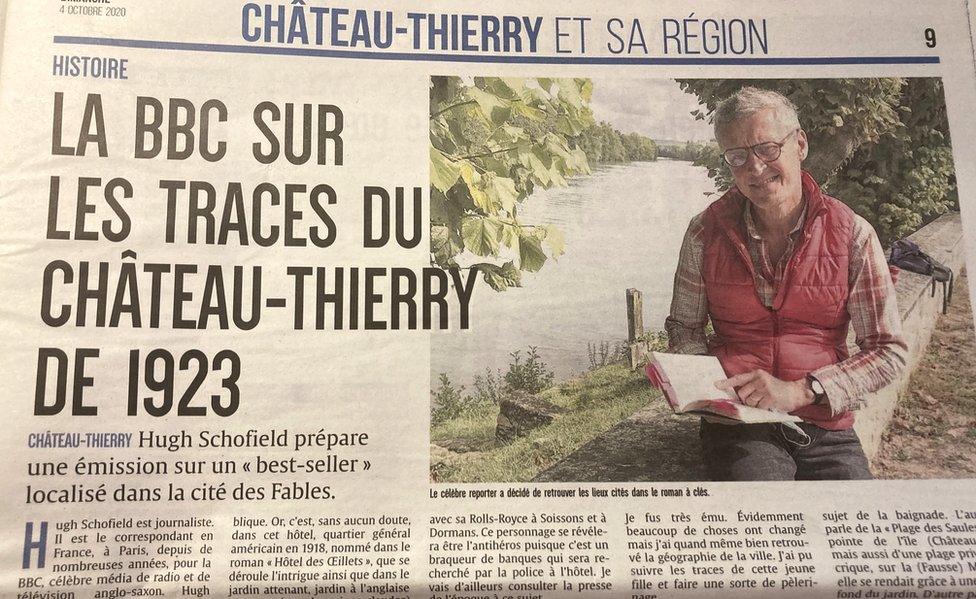

Hugh's hunt for the town's literary secrets has captured local headlines in the Marne area of northern France

At the Carnegie Library in Reims, I searched through old copies of Le Nord-Est, a local paper, for August and September 1923.

In vain. Nothing about a mysterious English Raffles debunking from a Château-Thierry hotel in the night.

Was her memory exaggerated? Was it novelistic licence? Was there ever a dashing English crook?

That mystery, I greatly fear, may never be resolved.

You might also like: