Bloody Sunday 1920: Croke Park killings remembered 100 years on

- Published

Torches were lit in Croke Park in tribute to the victims of Bloody Sunday

The victims of Ireland's original Bloody Sunday have been commemorated at a ceremony in Dublin.

On this day 100 years ago, British forces opened fire on the crowd attending a Gaelic football match in Dublin's Croke Park stadium.

Fourteen people were killed or fatally wounded and dozens more were injured.

The killings took place against the backdrop of the Irish War of Independence, a guerrilla conflict that began in 1919 between British forces and the Irish Republican Army (IRA), who sought Ireland's independence from Britain.

Earlier that Sunday morning, the IRA killed 14 people and wounded others in a series of co-ordinated attacks across Dublin, with the aim of assassinating British intelligence agents or spies.

The British authorities suspected some of the gunmen had disappeared into the crowd at Croke Park, so armed police were deployed to block all the exits and search thousands of spectators.

But, within minutes, panic ensued as police began shooting indiscriminately into the crowd.

The fatalities included three schoolboys aged 10, 11 and 14, and a bride-to-be who was due to get married within days.

Schoolboys William Robinson (11), Jerome O'Leary (10) and John William Scott (14) were among the dead

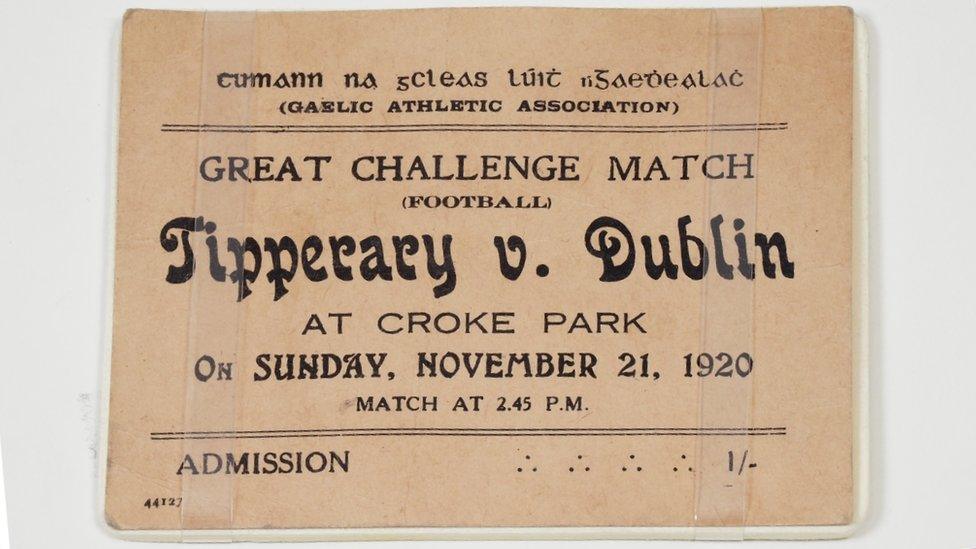

The Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA), which staged the fateful match between Dublin and Tipperary on Sunday 21 November 1920, hosted a remembrance ceremony in Croke Park on Saturday night.

Wreaths were laid in the stadium by Taoiseach (Irish Prime Minister) Micheál Martin and the President of Ireland Michael D Higgins.

Speaking about the event, President Higgins said: "That the events that took place can, in their brutality and casualness to the taking of life, still shock and challenge us all is to be understood.

"People from different backgrounds on the island may reflect on Bloody Sunday in different ways. We must respect this and be open to differing perspectives, and encourage a hospitality for these differing narratives of the events of that day."

The name of each victim and how they died was read out during an oration by actor Brendan Gleeson, as 14 torches were lit in their memory.

"They weren't just statistics," said Karina Leeson, a relative of William Robinson, the first person who was shot that day.

"They were people with families who loved them and who suffered greatly after their loss."

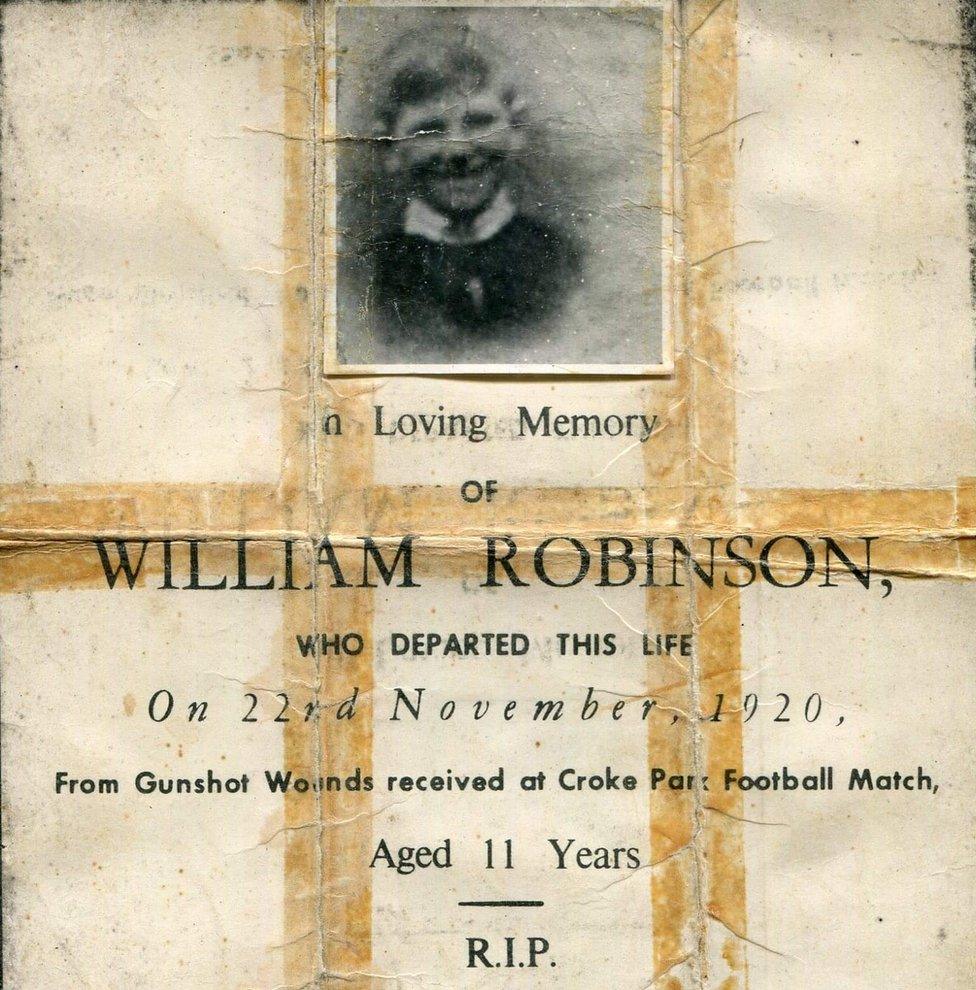

William Robinson was taken to hospital where he later died from his wounds

Eleven-year-old William Robinson, who had climbed a tree above the sports ground to get a better view of the match on Bloody Sunday, was shot in the chest.

"It's a horrific story... his parents never got over it," said his great-grandniece Ms Leeson.

"It was so tragic for the family that it was never openly spoken about."

Ms Leeson said she hoped the 100th anniversary would be a chance for the public to remember the ordinary football fans who simply went to a match and never came home.

An estimated 15,000 people attended the match on Sunday 21 November 1920

Author Michael Foley, whose research has been central to the GAA's centenary commemorations, believes most of the victims were previously forgotten by wider society.

"For an event that we were brought up with, one that was a real landmark moment in history, we knew nothing about it," he said.

In fact, in the tense aftermath of the shootings, more than half of the Croke Park victims were buried in unmarked graves - a point highlighted in his 2014 book, The Bloodied Field.

Five years ago, Mr Foley and several relatives began working with the GAA on a project to erect headstones for eight victims who had no marked graves.

The late Nancy Dillion, born three months after her father was killed on Bloody Sunday, witnessed the unveiling of his new headstone in 2016

The author argued that the loss of the victims' stories allowed myth and misinformation to creep into public memories of Bloody Sunday, masking what he called the real complexity of the event.

Croke Park's 14 victims included four IRA men and a former British soldier, reflecting the complex identities within the GAA and Ireland as a whole during the revolutionary period.

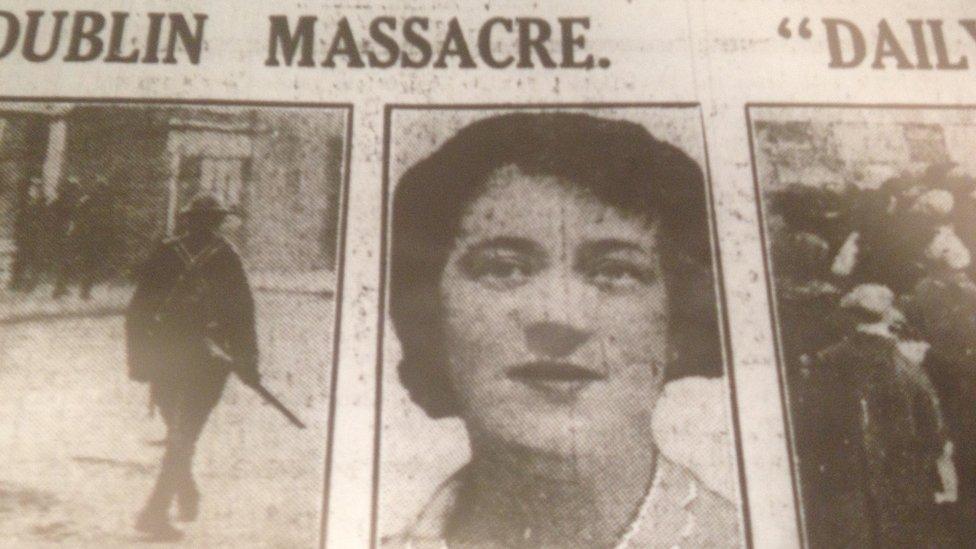

But those killed included ordinary Dubliners like Jane Boyle, a shop worker who had been due to get married in five days.

Her wedding plans were replaced with funeral preparations and the bride-to-be was buried in her wedding dress.

Bride-to-be Jane Boyle was one of the victims on Bloody Sunday

The outrage about police firing into crowds of men, women and children at a football match still reverberates in Ireland.

The shootings were carried out by a combined convoy of Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) officers and two RIC reserve forces - the Auxiliaries and the Black and Tans.

Two British military inquiries, held behind closed doors, criticised the RIC and Black and Tans for using "excessive" force, but exonerated the police from claims they fired the first shots.

'Catastrophic collapse in discipline'

The findings contradicted many eyewitness accounts, including that of Major Edward Mills, the officer in charge of a joint force of RIC and Auxiliaries that day, who criticised his own men for "indiscipline".

The GAA Museum describes Bloody Sunday as an "act of deadly retribution" for the IRA assassinations earlier in the day.

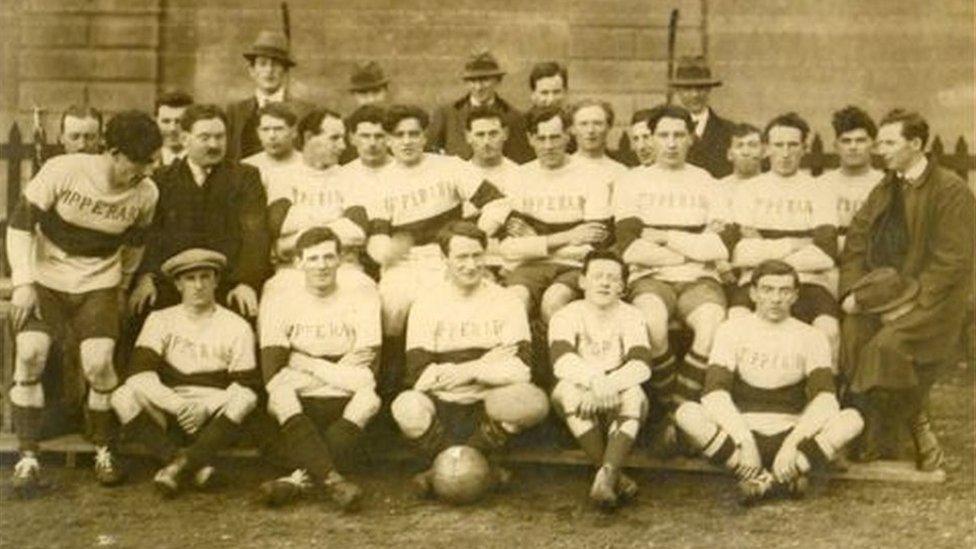

The Dublin team accepted Tipperary GAA's challenge to play at Croke Park on 21 November 1920

Mr Foley, however, believes the Croke Park deployment genuinely began as a search operation, but ended in death due to a "catastrophic collapse in discipline" among a small number of police.

The scale of that morning's IRA assassinations was unprecedented, he said, and the British authorities did not think the Dublin IRA was capable of carrying out such attacks alone.

They suspected IRA members from outside the city had travelled to Dublin in the guise of GAA fans.

The Tipperary Gaelic football team were lined up by armed police at one point and threatened with death

The GAA was viewed by some in the British establishment as "the IRA at play", according to Mr Foley, whereas he said it was a "broad church" encompassing people from many different backgrounds.

"Some people in 1920 would have seen the GAA as an extension of their political beliefs, but the vast majority were there to watch and enjoy the game," he added.

"The number of GAA members who fought in World War One is also indicative of the complex and colourful relationship that has always existed there."

IRA goalie

That patchwork of identity can also be illustrated by the teams on the pitch on Bloody Sunday and by the stories of those who died watching them play.

Just hours before the match, the Dublin team's goalkeeper Johnny McDonnell had taken part in one of the IRA attacks, during which two British intelligence officers were shot on Upper Mount Street.

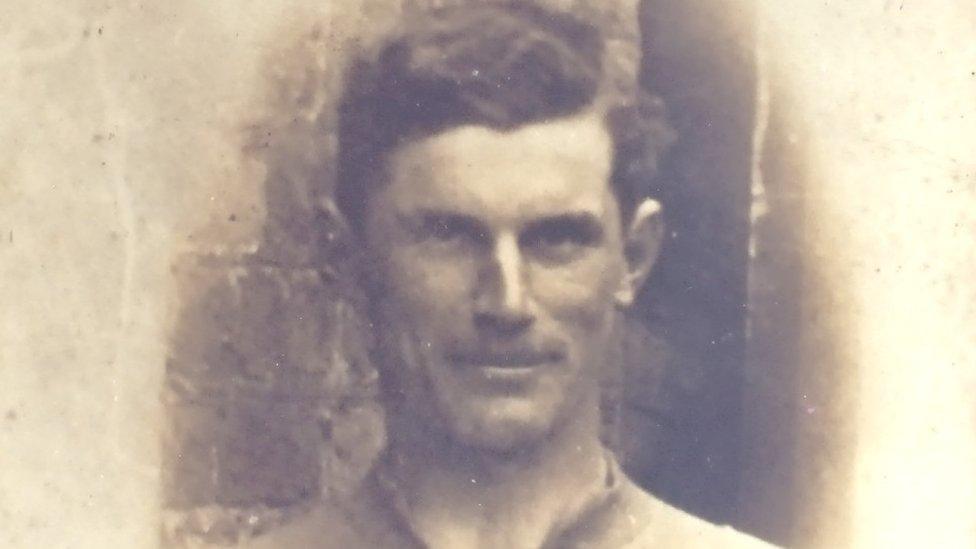

Tipperary player Michael Hogan - the most high-profile figure among those killed at Croke Park - was also an IRA member who had carried IRA messages from Tipperary to Dublin that weekend.

The GAA later named Croke Park's Hogan Stand in memory of Tipperary player Michael Hogan

But Hogan's teammate, Tipperary goalkeeper Frank Butler, was a former British soldier who had fought at the Somme.

Another former soldier, Michael Feery, was among the GAA fans who died. He was still wearing British Army fatigues when he was taken to hospital.

Spectator Patrick O'Dowd, who has been hailed as a hero for helping other fans escape from Croke Park, was shot dead as he pulled another British soldier over the wall to safety.

On the 99th anniversary last year, relatives of Patrick O'Dowd and Michael Feery joined GAA officials in unveiling new headstones on the site of their graves.

Relatives of Patrick O'Dowd attended a ceremony as a new headstone was unveiled in 2019

According to Mr Foley, the Bloody Sunday graves project has reshaped the GAA's relationship with victims' families, some of whom felt abandoned after the massacre.

In January 2020, the GAA invited the families to an event to discuss plans for the centenary.

"Their relatives are locked together in history, but that was the first time in 100 years that the families were brought together in one room," Mr Foley recalled.

Efforts were made to ensure the centenary commemoration focused on their personal stories.

"We're trying to portray an image of 14 people, not a statistic, but 14 individuals across a range of schoolboys, a girl who was due to get married, fathers, brothers," said GAA president John Horan.

Karina Leeson presents the William Robinson Cup, one of three GAA youth competitions named after the three schoolboys killed on Bloody Sunday

However, the coronavirus pandemic and the current restrictions on public gatherings meant commemorations had to be scaled back significantly.

Ahead of Saturday's ceremony, the GAA called on its membership to light a candle in their own homes in memory of the 14 victims.

Ms Leeson said it was heartbreaking that her family and others could not attend the Croke Park ceremony, but said they would be watching it on television.

Her family plans to organise a future celebration of William Robinson's life, when public health restrictions allow.

This article was updated 21 December 2020 to include comments from the President of Ireland Michael D Higgins.

Related topics

- Published17 January 2020

- Published21 November 2015