Daniel Cordier, from French Resistance hero to art dealer

- Published

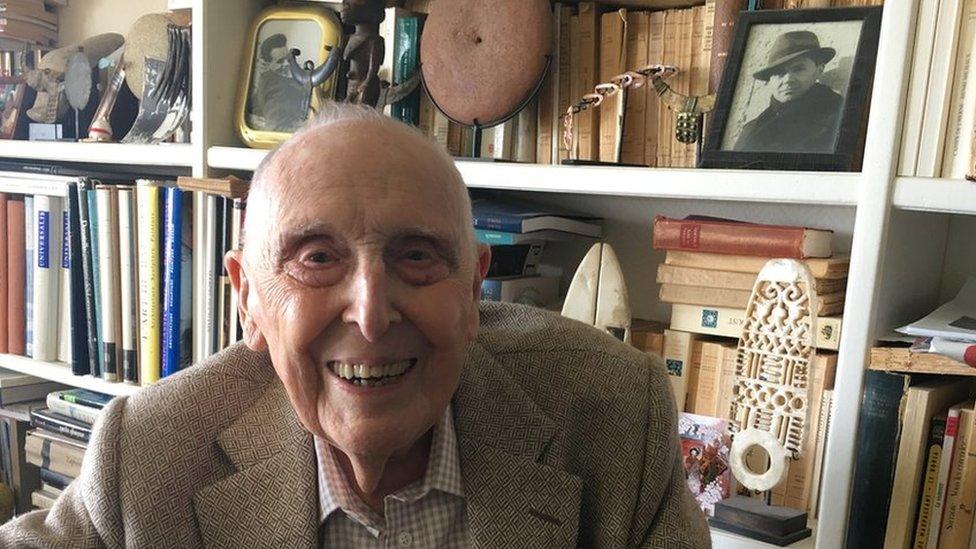

A picture of Jean Moulin sat on Daniel Cordier's bookshelf at his home on the French Riviera

French Resistance figure Daniel Cordier - who has died at the age of 100 - was one of the last remaining heroes decorated by Charles de Gaulle for their role in fighting the Nazi occupation.

His death on Friday leaves only one survivor among the 1,038 men and women who received the title "Compagnons de la Libération" after World War Two.

The son of a wealthy merchant in south-western France, Cordier first became involved in politics in the 1930s as a teenage member of the royalist far-right.

In June 1940, after German forces crushed the French army and the government of Marshall Philippe Pétain sued for peace, Cordier's activism took a different turn.

"As my mother collapsed into my stepfather's arms, I raced upstairs and flung myself on my bed, and I sobbed. But then (…) I suddenly drew myself up, and I said to myself, 'But no, this is ridiculous," Cordier recalled in a 2018 interview with the BBC. "[Pétain] is just a stupid old fool! We have to do something."

Daniel Cordier left to join the Free French in 1940 and returned in 1942

Three days later he and a few friends boarded a ship bound for French Algeria, which was seen as shelter for patriots who refused to surrender. But the vessel was diverted to Britain, where Cordier joined de Gaulle's Free French.

He joined the movement's intelligence arm and was parachuted into central France in mid-1942. A high point in his life was his meeting with Jean Moulin, the man tasked by de Gaulle to co-ordinate Resistance groups.

Cordier had come to deliver a message. The two men hit it off and he became the commander's right-hand man, based in Lyon.

"I admired Jean Moulin from the moment I first saw him," Cordier told the BBC. "He had an elegance and a kindness, and also a huge capacity for work. In his view, he was the Resistance. I hope in my own small way I was able to serve him as he wanted."

Reinventing himself

Ten months later Moulin was betrayed to the Gestapo and killed under torture. Cordier moved to Paris, where he continued to rally the resistance before escaping to London in 1944.

After the war he became a painter and a successful art-dealer, promoting contemporary masters such as Braque and Dubuffet.

He later credited Jean MouIin for initiating him into modern art. The education, he said, had begun as a kind of code. Moulin, he once said, decided to give him loud lectures on painters so as not to arouse suspicion when out and about in the danger zone that was occupied France.

Cordier took part in World War II commemoration ceremonies until his late 90s

Focused on his passion for art, Cordier did not speak publicly about his wartime past for decades. But he broke his silence in the 1970s, when a fellow Resistance hero portrayed Moulin - a hallowed figure in France - as a shambolic self-promoter and a Soviet agent.

Outraged, Cordier decided to clear his former boss's name. Delving into his Resistance past, he sifted through Resistance archives and interviewed survivors.

"I knew it was not true. But to prove it, I had to go back to the records," he told the BBC in 2018. The work culminated in the publication of influential biographies of Moulin in the 1980s and 1990s.

Controversy among historians continued over the nature of Moulin's links with the Communists - who after all were a key component of the Resistance Jean Moulin worked to unify. But Cordier's historical work helped refute many of the wilder allegations.

His effort to expose the truth did not end there. In a 2009 autobiography Cordier came out as gay, saying it would have been "utterly unthinkable" when he was young.