How close to a Brexit trade deal are we?

- Published

The EU and UK are still divided over some key Brexit files

"Almost nearly there" is an expression I learned years ago from one of the BBC's producers in Gaza.

An extremely talented journalist, infamous for his appalling time-keeping, he'd already called an hour before to say he'd soon be at the office. Bottom line, though: he wasn't there.

And so with the post-Brexit trade deal. We keep being told that "95% of the deal is agreed", that progress is still being made on issues that have long ceased to be contentious for either side - like social security and police co-operation.

But on the three red-raw, sore subjects, divisive from the very beginning: fishing rights, competition rules and the governance of the deal - "significant divergences" remain.

So we're almost nearly there on a deal. But not.

Politics v pragmatism

With only just over a month to go before the transition period ends, the rumour mill keeps churning relentlessly. Runes are read out loud, and potential - though never confirmed - compromise solutions are leaked to the hungry UK media (the European press is rather more preoccupied by Covid-19 and Christmas plans).

The EU's chief negotiator Michel Barnier spoke on Friday to EU fishing nations - does that mean a deal is nigh? He travels later on Friday to London - is this more significant now than the last countless times he's taken the journey?

Prime Minister Boris Johnson appoints a new chief of staff, Dan Rosenfield, who insists, it is said, "on the rule of law". Does this mean the government won't be reintroducing the clauses contradicting the Irish Protocol, signed last year with the EU, into its Internal Market Bill? Would the EU then be more likely to agree a deal?

And when is the last moment a deal can be signed?

Despite all the talk of "significant ongoing differences", the EU and UK could agree a deal very quickly indeed if - and it's the multi-million dollar if - both sides are willing to move.

The reason an agreement could be swift, if compromises are forthcoming, is that after all these negotiating rounds the practical, legal issues are crystal clear to both sides.

What I'm not sure is so clear - and it was ever thus - is each side's political understanding of the other.

If the UK is holding off making compromises, in the hope of squeezing more last-minute concessions out of Brussels, it might be successful when it comes to fish.

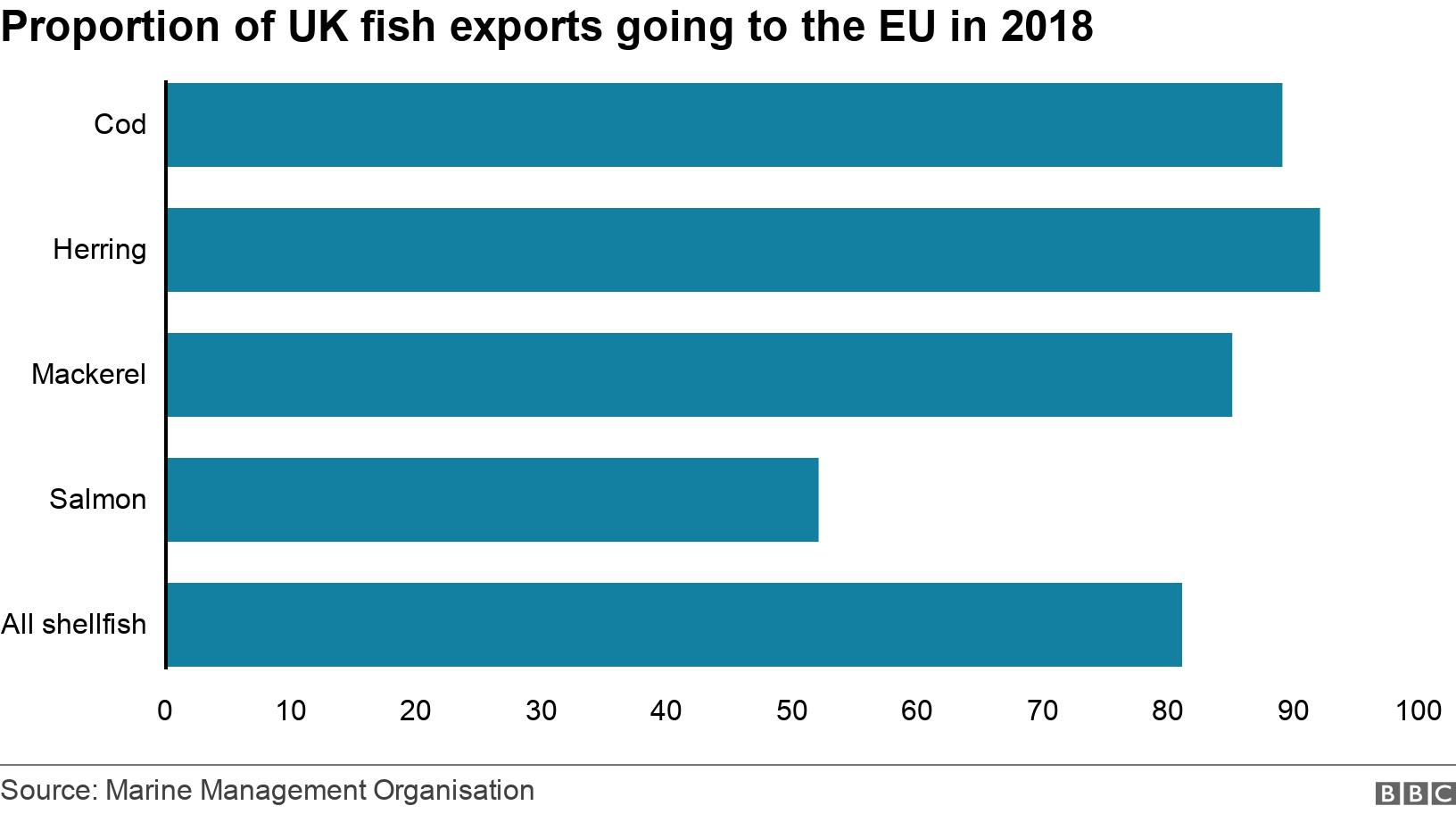

On Friday we heard talk of Michel Barnier being about to propose that between 15% and 18% of the fish quota caught in UK waters by EU fleets would be restored to the UK under a free trade agreement. That was later dismissed by a number of European diplomats, as merely one of "many proposals doing the rounds".

But whatever happens on the fish front - and Brussels knows it has some big compromises to make - as much as the EU wants a deal with the UK, it's unlikely to let go of its insistence on two other issues: common competition regulations and a tough means of policing them.

As we've heard and seen over the last years, EU governments and businesses value their lucrative single market above trade with the UK.

German car manufacturers have so often been named by ardent Brexiteers as key examples of Europeans who would push for a "special deal" with the UK. But they have been among the most insistent that they wouldn't want a deal if it meant compromising the single market business model.

Confused by Brexit jargon? Reality Check unpacks the basics.

And what of Brussels, does it still misread Boris Johnson - underestimate the pressure the prime minister, already beleaguered domestically over his handling of the coronavirus crisis, feels from Brexit hardliners in his own ranks?

Does the EU still fundamentally misunderstand what Brexit was about, at least from the government's perspective?

The EU's underlying belief is that the UK should sign up to this trade and security deal. Because it makes "practical sense" for both sides.

But on Friday, the UK's chief negotiator, David Frost, tweeted once again that any deal had to "fully respect UK sovereignty".

He said that included "controlling our borders, deciding ourselves on a robust and principled subsidy control system; and controlling our fishing waters".

Would winning back even 15-18% of fish stocks equate to "taking back control" of UK waters after Brexit? Bear in mind that EU coastal nations object to relinquishing even that much as being "a very high price to pay".

Would accepting common competition principles with the EU on government subsidies and labour regulations be a sovereign UK deciding what's in its own long-term interest? Or would it signify a "betrayal" of Brexit?

So many Brexit deadlines have already been smashed by now. Of course, the absolute full-stop is one set in EU and UK law: 31 December, the end of the transition period.

After that, the EU and UK can keep negotiating if they want to, but the two sides would have to trade under tariff-heavy World Trade Organization (WTO) rules. The UK would have no access to the EU's energy market, no agreement on police and judicial co-operation, and the separate EU decision on which UK financial services could work in the single market could well be adversely affected.

If an agreement is reached by the year's end, it also needs to have been signed off, however hurriedly, by EU leaders and by parliament in the UK. If necessary the European Parliament, through gritted teeth, can vote in the New Year. The deal can go into effect provisionally in the meantime.

EU leaders hold their next summit on 10 December. That, in Brussels at least, is widely viewed as the latest Brexit whisper of a time by which the trade and security deal with the UK must be - not "almost nearly" - but really, truly there.

Otherwise, the no-deal situation looms large.

- Published27 November 2020

- Published30 June 2021

- Published18 November 2020

- Published3 February 2020

- Published23 December 2021