Irish government to apologise over mother-and-baby homes

- Published

The scandal became an international news story when "significant human remains" were found on the grounds of a former home in County Galway

The Irish government is to apologise after an investigation found an "appalling level of infant mortality" in the country's mother-and-baby homes.

Established in the 19th and 20th Centuries, the institutions housed women and girls who became pregnant outside marriage.

About 9,000 children died in the 18 institutions under investigation.

The government said the report revealed the country had a "stifling, oppressive and brutally misogynistic culture".

Taoiseach (Irish Prime Minister) Mícheál Martin said the report, which can be read in full here, external, described a "dark, difficult and shameful chapter" of Irish history.

"As a nation we must face up to the full truth of our past," he said.

The commission that investigated the homes found that the number of children who died was about 15% of all those who were born in the institutions.

There were about 56,000 unmarried mothers and 57,000 children in the homes investigated by the commission.

PJ Haverty explains what life was like for him after being born in Tuam mother-and-baby home

The greatest number of admissions was in the 1960s and early 1970s.

Many children born in the homes were adopted or taken to orphanages run by Catholic nuns.

The report said "the women and children should not have been in the institutions" and that many women suffered emotional abuse.

The investigators said it appeared there was "little kindness" shown to the mothers and "this was particularly the case" during childbirth, which many of the women found to be "a traumatic experience".

'Warped attitudes'

Mr Martin is to issue a full apology on behalf of the state in the Dáil (Irish parliament) on Wednesday.

Speaking on Tuesday, he said "one hard truth" was that "all of society was complicit" in the scandal.

Taoiseach Micheál Martin: "We treated women and children exceptionally badly"

"We did this to ourselves as a society - we treated women exceptionally badly; we treated children extremely badly," said the taoiseach.

"We had a completely warped attitude to sexuality and intimacy and young mothers and their sons and daughters were forced to pay a terrible price for that dysfunction.

"As a society we embraced judgementalism, moral certainty, a perverse religious morality and control which was so damaging.

"But what was very striking was the absence of basic kindness."

Archbishop Martin apologised to survivors for the long-lasting hurt and emotional distress they suffered

The leader of the Catholic Church in Ireland, Archbishop Eamon Martin, said he accepted that the Church was part of a culture in which "people were frequently stigmatised, judged and rejected".

"For that, and for the long-lasting hurt and emotional distress that has resulted, I unreservedly apologise to the survivors and to all those who are personally impacted by the realities it uncovers," he said.

"I believe the Church must continue to acknowledge before the Lord and before others, its part in sustaining what the report describes as a 'harsh… cold and uncaring atmosphere'."

The Church needed to find ways of reaching out to those who have spoken of their experiences in the report, he said.

Archbishop Martin urged anyone who could help locate the burial places of those who died in the mother and baby homes to come forward.

Children's Minister Roderic O'Gorman said the report showed that for decades a "pervasive stigmatisation of unmarried mothers and their children robbed those individuals of their agency and sometimes their future".

The commission has made 53 recommendations, including compensation and memorialisation.

Its report stated that while mother-and-baby homes existed in other countries the proportion of unmarried mothers who were in the institutions in Ireland was probably the highest in the world.

Catherine Corless carried out research in a bid to find the graves of infants who died at Tuam

"In the years before 1960 mother-and-baby homes did not save the lives of 'illegitimate' children; in fact they appear to have significantly reduced their prospects of survival," stated the report.

"The very high mortality rates were known to local and national authorities at the time and were recorded in official publications."

The Sisters of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary, which ran some of the homes, said it was a "matter of great sorrow to us that babies died while under our care".

"We especially want to recognise and accept today that so many women who were shunned and shamed by society did not find the support and level of care they needed and deserved at such a dreadful and painful time in their lives," said the group.

"We want to sincerely apologise to those who did not get the care and support they needed and deserved."

Hundreds of babies dead at one site

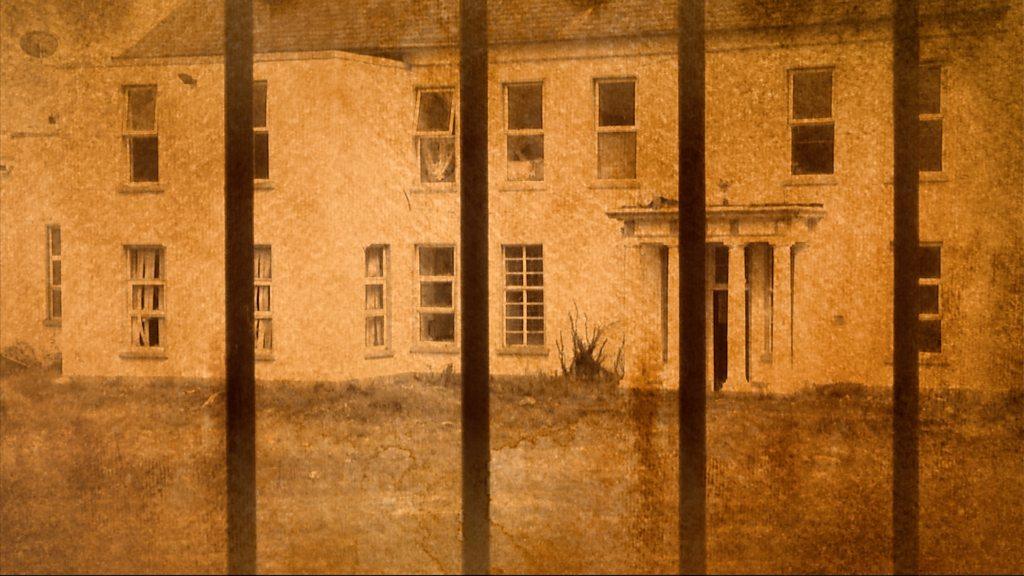

The homes became an international news story in 2014 after a substantial amount of human remains was found in the grounds of a former home in Tuam, County Galway.

Local historian Catherine Corless found that 796 children had been buried there.

Catherine Corless watched the taoiseach speak to survivors of the homes before the report was published

In response, the Irish government established an independent Mother-and-Baby Homes Commission.

In an interim report, the commission found that some babies were buried in 20 chambers inside what was a larger decommissioned sewage tank.

Speaking after the publication of the final report, Ms Corless was critical of how the government had presented it to the survivors of the homes.

The taoiseach had spoken to them in an online briefing on Tuesday before the report was made public.

"It was highfalutin talk... a lot of waffle, you could say," she said.

"A lot of the survivors are very, very upset, they feel they're just being thrown redress - pay them off and just forget about everything."

Annette McKay's mother was sent to the home in Tuam when she was 17 and believes her older sister could be one those buried there.

She has always hoped her sister's remains could be exhumed and identified, however while the report talks about a process of "respectful reburial", it will not begin until 2022.

She told PA: "I'm very sad. I was never optimistic. I was always full energy, that a fight could be won, and now I don't feel that. I feel defeated."

"It's very, very hard today to look at a picture of my mother and think 'another year mum, and we're no further on'. It's been a tough day."

The Tuam home was demolished but a shrine was later erected on the site

The commission said it found "very little evidence that children were forcibly taken from their mothers".

It continued: "It accepts that the mothers did not have much choice but that is not the same as 'forced' adoption'."

The report contains witness testimony from women who said they had not consented to their child being adopted.

Niall Boylan, who was born in the St Patrick's home on the Navan road in Dublin, has criticised the report's failure to deal with forced adoption.

"The report doesn't acknowledge that there was abuse, and they don't acknowledge that there was forced adoption. It's ridiculous."

Related topics

- Published11 January 2021

- Published14 September 2020

- Published26 October 2020