Olivier Duhamel: French incest allegations prompt victims to speak out

- Published

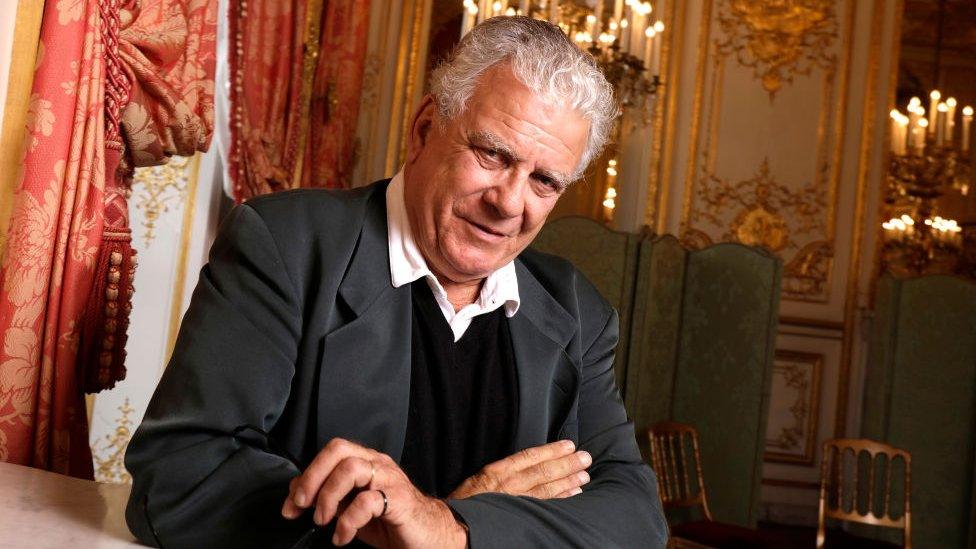

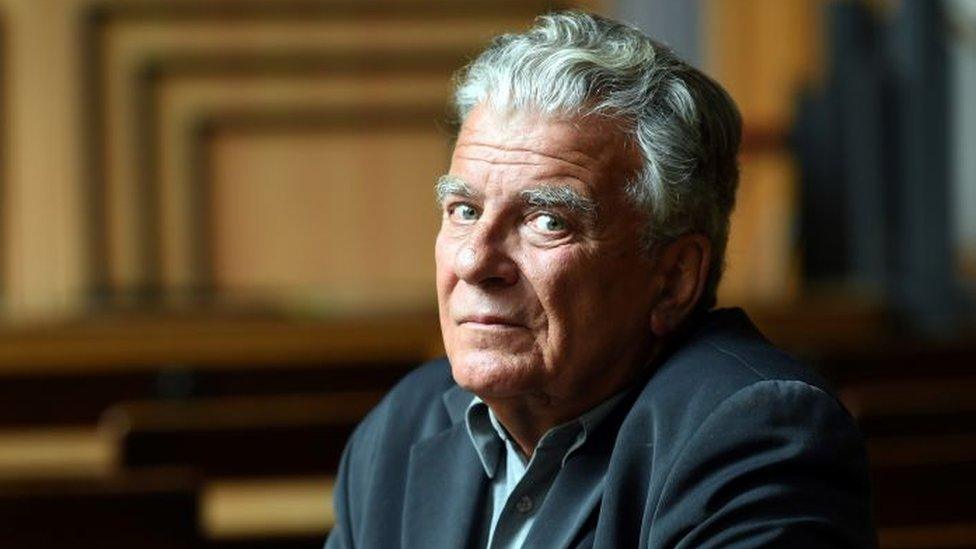

Olivier Duhamel has resigned as head of the National Foundation of Political Sciences, which oversees the prestigious Sciences Po university

Tens of thousands of people have responded to a social media campaign in France designed to shed light on the problem of sexual abuse within families.

The campaign, featuring the hashtag #MeTooInceste (after the #MeToo movement) was started over the weekend by NousToutes, an organisation battling sexual violence in France. Incest in French is used to mean sexual abuse by relatives, including those who are not related by blood.

It followed accusations against a prominent political commentator, Olivier Duhamel, who has been accused by his stepdaughter of abusing her twin brother 30 years ago. Mr Duhamel has described the allegations as "personal attacks".

The Twitter campaign began late last week with a message by a 67-year-old NousToutes activist known as Marie Chenevance.

"It was now or never to break the omerta [code of silence] around this issue," Marie said. In earlier years, she said, activists had met a "wall of silence" when they shared their stories of family abuse.

More than 80,000 people have responded to the campaign since Saturday, the organisation says.

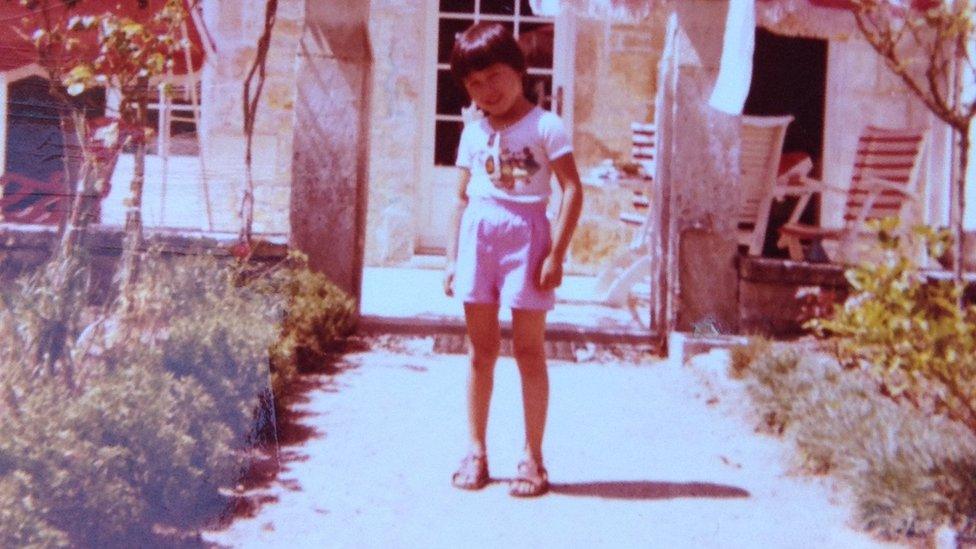

Mié Kohiyama says her story is only now being heard

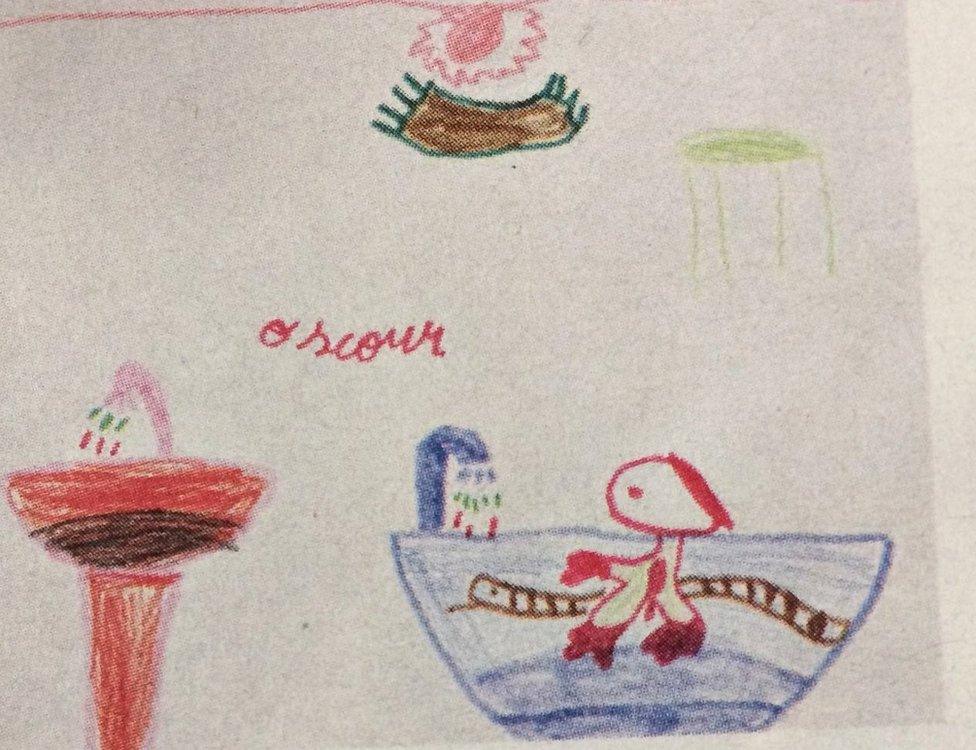

Mié Kohiyama was one of those who shared her story, alongside a drawing she made when she was five years old.

The picture shows a child with no mouth, alongside the words "Help Me" ("au secours", which she spelt "o scour"). Back then, it was her way of speaking about the abuse, she said, but no-one heard the message.

"On Saturday, when I posted this tweet," she told me, "it's strange to say, but I was proud of the little girl who drew this picture.

"I tell myself that now people can understand these kinds of drawings. Forty years before, it was not possible."

Culture of secrecy

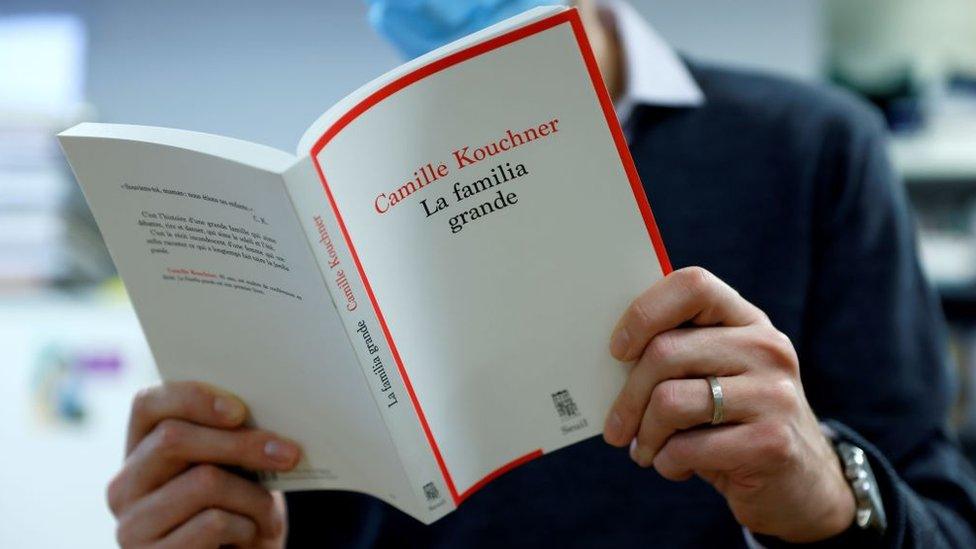

Part of the reason the accusations against Mr Duhamel have had such an impact, activists say, is that the account of his stepdaughter Camille Kouchner in her book La Familia Grande describes not just the alleged behaviour itself, but the culture of secrecy that she says surrounded the family.

Muriel Salmona, a leading psychologist specialising in sexual violence, says that the issues raised by Mr Duhamel's stepdaughter along with the launch of the new hashtag opened up a "safe space" for victims to speak out.

Historically, she says, there has been "almost-total impunity in France" for family abusers, with less than 1% of rape cases against minors ending up in court.

"The figures on violence against children are bad for most of Europe," Dr Salmona explained. "But in France there is a current that tolerates sexual violence against children."

The law around this issue is complex. Sex with minors is illegal, but in order to prove the more serious charges of rape or sexual assault - including of a child - it's necessary to prove that violence, threat, surprise or coercion were used.

If the perpetrator is much older than the victim, or in a position of authority, it can be viewed as coercion, but Dr Salmona says it's not automatic.

This means that, legally speaking, a child as young as 11 years old can be considered to have consented to sex with an adult.

Campaigners have long been asking for a legal age of consent, but repeated attempts to get the law changed have so far failed.

A poll at the end of last year suggested that one in 10 people in France had experienced childhood sexual abuse within the family.

Marie Chenevance said she knew there would be a large number of people affected by the new campaign, but was surprised at the outpouring of testimony.

"On the one hand, the stories are sad," she said, "but on the other hand, it feels good - it's liberating."

More stories on sexism and harassment

Find out more on France and the #MeToo movement

Allow YouTube content?

This article contains content provided by Google YouTube. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Google’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Related topics

- Published5 January 2021

- Published19 January 2020