Russian anti-Putin anger spreads: 'We have to protest'

- Published

Detained protesters in Moscow: Filip Kuznetsov is front right

Filip Kuznetsov spent an entire night crammed into a police van with 17 other protesters because Moscow's detention centres were all full.

He was among a record 4,002 people arrested across Russia last week, as large crowds took to the streets to demand the release of the opposition politician Alexei Navalny. Further protests have been called for Sunday, threatening to strain the system even further.

"We didn't sleep all night. One person always had to stand for space, so we took it in turns," Filip told me by phone on Wednesday from the back of the police van, which he described as an "ancient vehicle with metal bars all round".

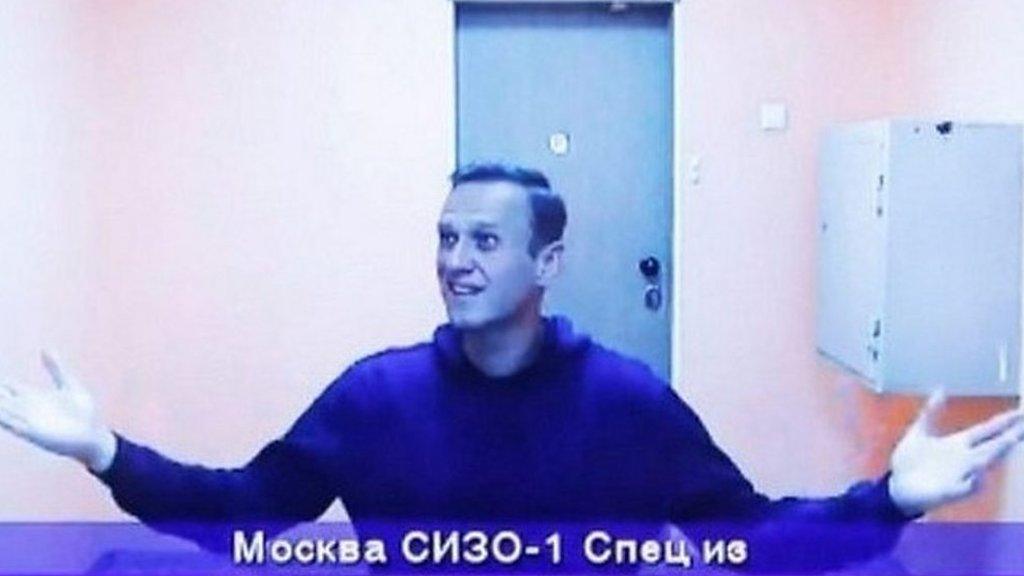

Anti-corruption campaigner Alexei Navalny, fiercely critical of the Kremlin, was imprisoned on his recent return to Russia after recovering from an attempt to kill him with a nerve agent.

Alexei Navalny says the latest case against him was fabricated

A judge had sentenced Filip to 10 days in custody on Monday for his part in the protest. But it took police a further two days to find space in city cells. By the time we spoke, his group had been waiting outside Moscow Detention Centre No 2 for 17 hours, fed only by volunteers who brought sandwiches to the van.

'Anyone could be next'

Filip, a small-business owner, is not a fan or follower of Mr Navalny, but he is disturbed by how a fellow citizen is being treated.

"They're punishing him for nothing - which means anyone could be next, including me," he explained.

Many of the Moscow protesters had taken to the streets for the first time

Few protesters we spoke to at Moscow's Pushkin Square last Saturday mentioned Mr Navalny's near-fatal poisoning, but all were shocked at how his flight home had been diverted so he could be detained at the border. He then faced a bizarre, makeshift court hearing in a police station.

One poll suggests as many as 42% in the Moscow crowd were moved to protest for the first time. The rallies were also unprecedented in their spread, covering towns and cities usually seen as politically "passive".

The biggest demonstration was in central Moscow, but there were protests in dozens of cities across the country

"In Moscow, we have safety in numbers, places to work if we get fired, but in the regions it's much more constricted," political scientist Ekaterina Schulmann points out. "People there take higher risks."

'In the regions people are much angrier'

In Vladivostok, Russia's far east, Mr Navalny's team say there haven't been demonstrations in the city on last Saturday's scale for over a decade.

Katerina Ostapenko, his local co-ordinator there, did not take part herself: she was picked up by police the day before. But she says up to 3,000 people came out, motivated partly by Navalny's latest video exposé: a corruption investigation targeting President Vladimir Putin himself.

Katerina Ostapenko organises for Mr Navalny in Vladivostok

The film claimed that Mr Putin had a secret, opulent palace, external built for him on the Black Sea, complete with an aqua-disco and a pole-dancing salon.

"I think people in the regions are much angrier and that's why so many protested," Ms Ostapenko told me. "They're really angry because they have no money, and now look how much Putin has! And it's our tax money that paid for his palace."

Vladimir Putin has denied any link to the giant property in Gelendzhik, calling the film a poor montage meant to brainwash people. It's already been watched on YouTube more than 100 million times.

"The number of views is staggering," Ekaterina Schulmann says, arguing that the scale of subsequent protests reflects deepening discontent here.

The much-watched video claims the property features a casino, an ice rink and a vineyard

"[There's] the year of lockdown measures, the frustration and weariness collected inside people in that time, and the ongoing economic stagnation and declining incomes," she notes, adding that Mr Putin's trust rating has been sliding since his re-election two years ago.

"We are in a turbulent period."

So, unsurprisingly, the response to Saturday's protest has been swift and hard.

After rounding up thousands of protesters on the day, issuing fines or short-term detention, officials are now going after key allies of Alexei Navalny including his brother, doctor, and a lawyer at his Anti-Corruption Foundation.

Alexei Navalny's brother Oleg (left) was taken to court on Friday after being arrested at his flat in Moscow

Police in black balaclavas, armed with crowbars, launched raids at their flats and offices across Moscow, as a criminal case was opened for calling a protest mid-pandemic. The fact that Moscow's mayor just lifted a curfew on bars and nightclubs, claiming that Covid-19 is in retreat, made no difference.

On Friday, a court placed the three under house arrest for two months, barred from using the internet, while the investigation continues.

The Kremlin spokesman denies the prosecutions are politically motivated, telling journalists that law enforcement officers are "just doing their job".

But with another day of demonstrations ahead, the authorities clearly want to remove the ringleaders.

'We have to protest'

The crackdown may well shrink the crowd this weekend: criminal cases have been launched against ordinary protesters, too - serious charges, including violence against police and hooliganism.

Record numbers have been arrested in the capital in the past week

But many have vowed to come out regardless.

"We share one problem, the way we're governed," Danya says - a student who was detained last Saturday along with several friends. "We're all protesting for one thing: the alternation of power."

His friend Kirill says their group were standing quietly when the police "flew at us and started to beat us with their batons".

"I'm not a direct supporter of Navalny," Kirill explains, but he considers his treatment "illegal". "So as citizens of a country we love and want to be better, we have to protest."

One person who definitely won't join him is Filip Kuznetsov, who still has several days of his sentence left to run.

But on Friday he sent word that he and other protesters were being moved "at great haste".

"They're making space for the protest on the 31st," he messaged me, before being bundled into another police van and driven to a detention centre for illegal migrants 100km (60 miles) out of town.

Related topics

- Published29 January 2021