Alexei Navalny, Russia's most outspoken Putin critic

- Published

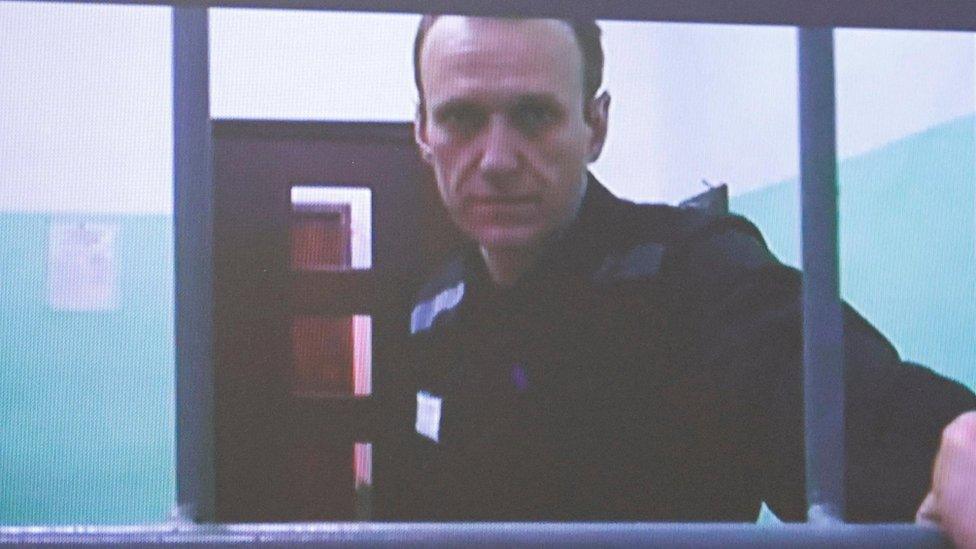

Anti-corruption campaigner Alexei Navalny was long the most prominent face of Russian opposition to President Vladimir Putin.

The 47-year-old blogger had survived poisoning attempts and years in some of Russia's most notorious jails, after his group had exposed corruption at almost every level of the Russian state - frequently targeting President Putin himself.

Even from behind bars, unable to challenge the president at the ballot box, his voice had retained power.

But in February 2024, it fell silent. According to the prison service, he had gone for a walk when he lost consciousness and died.

In the immediate aftermath, the Kremlin simply said that it was aware of his death, and the president had been informed.

Across the world, however, there was shock and anger, as tributes were paid to a man who some said gave his life standing up to Russia's all-powerful leader.

Alexei Navalny was born in 1976, in a village just to the west of Moscow. He grew up in Obninsk, a town 100km (62 miles) south-west of Moscow, eventually graduating in law at Moscow's Peoples' Friendship University of Russia in 1998.

But it was another decade before he began his rise as a force in Russian politics, making his name as a grassroots anti-corruption campaigner. His blog took aim at alleged malpractice and corruption at some of Russia's big state-controlled corporations.

One of his tactics was to become a minority shareholder in major oil companies, banks and ministries, and to ask awkward questions about holes in state finances.

His consistent message was a simple one: that Mr Putin's party was full of "crooks and thieves".

UKRAINECAST: Navalny: What next for Russia?

He accused the president of "sucking the blood out of Russia" through a "feudal state" concentrating power in the Kremlin. That patronage system, he claimed, was like tsarist Russia.

It helped that Navalny spoke the street language of younger Russians, and used it to powerful effect on social media. His Anti-Corruption Foundation (FBK) made detailed claims about official corruption.

Then, in 2011, he would lead large street protests against President Putin.

Navalny's wife Yulia, pictured with him in 2015, was at most court cases to support him

For the rest of his life, he would be in and out of jail, while his organisations would be banned as "extremist".

In 2017, he was barred from standing in the general election. At the time, he was widely regarded as the only candidate with a chance of challenging President Putin.

He would also survive several suspected - and one confirmed - attempts on his life.

The Novichok poisoning

The first time Navalny suspected he had been poisoned, he was in prison serving a sentence for calling for unauthorised protests. Then 43, he was taken to hospital with a swollen face, eye problems and rashes on his body.

At the time, reports suggested it was an allergic reaction - something he and his doctor were quick to question. Officially, he was diagnosed with "contact dermatitis".

Navalny - who had previously suffered chemical burns to an eye after been targeted with antiseptic green dye in 2017 - later wrote that the doctors who treated him acted "like they had something to hide".

But it was the second alleged poisoning a year later which really caught the attention of the international media.

In August 2020, Navalny collapsed on a flight over Siberia and was rushed to hospital in Omsk. That emergency landing saved his life. A German-based charity persuaded Russian officials to allow him to be airlifted to Berlin for treatment.

In September, the German government revealed that tests carried out by the military found "unequivocal proof of a chemical nerve warfare agent of the Novichok group, external". The Kremlin denied any involvement and rejected the Novichok finding.

The EU then imposed sanctions on six top Russian officials and a Russian chemical weapons research centre, accusing them of direct involvement in the poisoning. Russia retaliated with tit-for-tat sanctions.

Novichok was the chemical weapon which nearly killed former Russian spy Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia in Salisbury, England, in March 2018. A local woman later died from contact with Novichok.

Mr Putin admitted that the state was keeping Navalny under surveillance - it was justified, he alleged, because US spies were helping the blogger.

Navalny - pictured with his family - was taken to Berlin for treatment after the Novichok poisoning in 2020

Recovered, Navalny returned to Moscow on 17 January 2021 and was immediately detained, as he knew he would be. He said on Instagram that he felt he had never left - so there was no choice but to return.

He would never be free again, despite his supporters staging mass protests across Russia. Police responded to the protests with force, detaining thousands for attending the unauthorised rallies.

The arrests did not deter his team from their mission. A video of "Putin's palace" on YouTube, external was quickly published, focusing on a vast luxury Black Sea palace, allegedly gifted to Mr Putin by rich associates.

The video has been viewed well over 100 million times. The Kremlin dismissed it as a "pseudo-investigation" and Mr Putin called it "boring", denying the claims. Later billionaire businessman Arkady Rotenberg, one of Mr Putin's closest friends, said it was his own palace.

The court case which followed allowed Navalny to make public his allegations against President Putin, in what was now an intensely personal battle: he accused the president of ordering state agents to poison him - and repeated that in court.

"His main gripe with me is that he'll go down in history as a poisoner," Navalny told the court scornfully. "We had Alexander the Liberator, Yaroslav the Wise, and we will have Vladimir the Underpants Poisoner."

Underpants had become a social media meme in Russia after Navalny carried out a telephone sting in December 2020 on a Russian FSB state security agent, who revealed that Novichok, a highly toxic Russian chemical weapon, had been smeared on Navalny's underwear.

But while it highlighted once more the Kremlin's alleged attempts on his life, it did not stop the court finding him guilty. On 2 February 2021, a Moscow court jailed Navalny for violating the terms of a 2014 suspended sentence for fraud - a case which he said had been politically motivated in the first place.

Meanwhile, he and his anti-corruption team - all banned from standing in parliamentary elections - were still fighting the Kremlin, this time creating a "smart voting" app that encouraged voters to back candidates who had a chance of defeating Mr Putin's United Russia party in September 2021.

Hundreds of protesters in Moscow were detained by police

But Navalny was not a simple hero, battling against a powerful regime. He has been accused of xenophobia.

In videos dating back to 2007, he is seen appearing to compare ethnic conflict to tooth decay and likened immigrants to cockroaches. He also said the Crimea peninsula "de facto belongs to Russia", despite international condemnation of Russia's 2014 annexation of the Ukrainian territory.

The comments led - controversially - to Amnesty International revoking his status as a "prisoner of conscience" in February 2021, before conceding it had been subjected to an "orchestrated campaign" to "delist" him and then reversing its decision.

Meanwhile, the Russian government continued to punish Navalny. In March 2022, his sentence was increased by nine-years after he was found guilty on new charges of embezzlement and contempt of court. He was moved to a new penal colony at Melekhovo, around 250km (150 miles) east of Moscow.

In June 2022, his allies raised the alarm after they discovered he was no longer in that prison. Federal prison authorities later admitted he had been moved to a penal colony with a tough reputation, the IK-6 prison, more than 155 miles (249km) east of Moscow, where he said he was repeatedly placed in solitary confinement.

His last sentence, handed down by judges in August 2023 and which extended his jail term to 19 years, saw him moved to a maximum security penal colony usually reserved for Russia's most dangerous criminals.

Watch: Navalny jokes in court a day before his death

His harsh treatment reflected the fact that Mr Putin and his regime feared the influence that Navalny's campaigns had been gaining, Prof Nina Khrushcheva, the great-granddaughter of former Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev and international affairs experts, told the BBC at the time.

"Putin doesn't even mention his name, anybody in the Kremlin can't his mention name," she said, drawing a comparison with the fictional Harry Potter character Voldemort - who is also referred to as "He-Who-Must-Not-Be-Named".

"Navalny is a threat to Putin's personal power, Putin's personal reputation of himself. And Putin doesn't really treat his enemies lightly and Navalny unfortunately took this - as they say in Russian - this ticket to be Putin's personal enemy."

Anti-corruption campaign

Yet despite the confinement of his last years, Navalny became one of the leading domestic voices against the war in Ukraine.

During a court appearance in May 2022, he accused Mr Putin of starting a "stupid war" with "no purpose or meaning". And in September, he accused Russian elites of having a "bloodthirsty obsession with Ukraine" in an article for the Washington Post.

His foundation also continued to oppose the government throughout his imprisonment, speaking out against the mobilisation of some 300,000 civilians to fight in Ukraine and pledging to be a "partisan underground" movement inside Russia.

Navalny told the BBC that the best thing Western states could do for justice in Russia was to crack down on "dirty money".

"I want people involved in corruption and persecution of activists to be barred from entering these countries, to be denied visas."

The news of his death on 16 February was immediately greeted by a wave of tributes from around the world.

He had made the "ultimate sacrifice" in his fight "for the values of freedom and democracy", said the European Union Council president Charles Michel, while French foreign minister Stéphane Séjourné said he had "paid with his life for his resistance to a system of oppression".

However, exactly how - or why - he died has yet to be established. He leaves behind his wife, Yulia, and two children.

According to his team, they had not been informed directly of his death when it broke in newspapers across the world.

"I don't know whether or not to believe the news, the terrible news", Yulia Navlanaya said at the Munich Security Conference, hours after news of her husband's death broke.

"You all know this - we can't believe Putin and Putin's government. They're always lying," she added.

"But if this is true, I want Putin and all of his entourage, Putin's friends and his government to know that they will be held accountable for what they have done to our country, to my family and to my husband."

She left the stage to a standing ovation.

Alexei Navalny: More coverage

OBITUARY: Russia's most vociferous Putin critic

BEHIND BARS: Life in notorious 'Polar Wolf' penal colony

IN HIS OWN WORDS: Navalny's dark humour during dark times

SARAH RAINSFORD: Navalny was often asked: 'Do you fear for your life?'

Related topics

- Published3 February 2021

- Published16 February 2024