Mother-and-baby homes: Questions raised over deleted recordings

- Published

The state-wide inquiry investigated 18 homes, including Sean Ross Abbey in County Tipperary

Concerns have been raised over the decision to delete audio recordings of witnesses who gave evidence to the Irish mother-and-baby homes inquiry.

The recordings were made when former residents were invited to tell their personal stories to the inquiry.

Its final report said people were informed before they gave evidence that the recordings would be destroyed.

But some witnesses dispute that and Ireland's data watchdog has questioned the legal basis for the deletion.

The Data Protection Commission has written to the Commission of Investigation into Mother and Baby Homes seeking answers about the deleted audio recordings, external.

'We spoke our truth'

Among the 549 witnesses who gave personal testimony to the inquiry's confidential committee was Clodagh Malone.

She was born in St Patrick's Mother and Baby Home in Dublin in 1970.

"I didn't think that the recording would be destroyed - absolutely not," she told BBC News NI.

Clodagh Malone was among campaigners who met Pope Francis during his visit to Ireland in 2018

Ms Malone is an adoption rights activist who also helps run the Coalition of Mother and Baby Homes Survivors campaign group.

She said after going through the trauma of sharing their "innermost secrets" with the inquiry, witnesses were deeply upset by the destruction of recordings.

She believes their testimonies should have been preserved in full for future generations.

"We spoke our truth... your truth belongs to you and they were there to listen and to record it for our children and grandchildren."

No burial records

The inquiry published its final report, external last month and among its findings was an "appalling" level of infant mortality in the overcrowded homes.

The commission concluded about 9,000 children died at 18 institutions during the 76-year period it was tasked to investigate.

Despite a six-year investigation, it could not find burial records or graves for hundreds of the children.

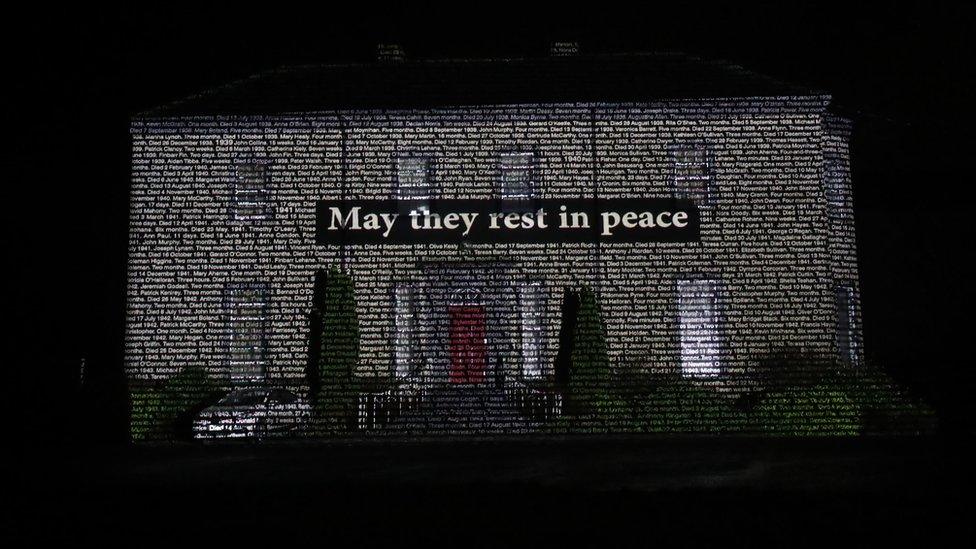

The names of hundreds of children who died in Bessborough Mother and Baby Home in Cork were projected onto Sean Ross Abbey in Roscrea last week

The findings prompted a state apology but many witnesses were disappointed and angry about how their evidence was presented and paraphrased in the report.

Ms Malone said some survivors barely recognised their own contributions and they now want access to their personal information gathered by the inquiry.

With the Commission of Investigation due to be dissolved on 28 February, campaigners are concerned about how records will be accessed after that date.

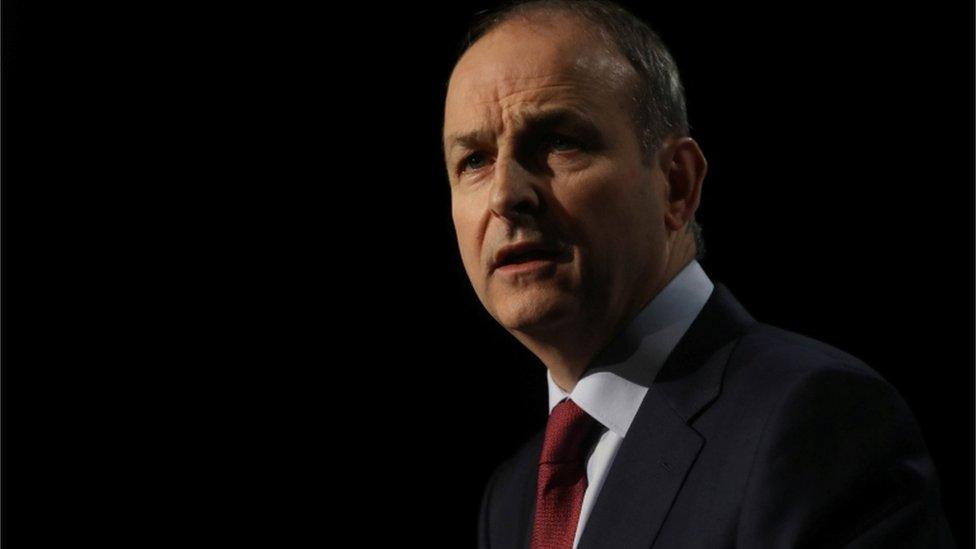

The commission's chair is Judge Yvonne Murphy (centre) who led a previous inquiry into clerical child abuse

Mother-and-baby homes were shrouded in secrecy and some witnesses who gave evidence to the inquiry were traumatised individuals who had never spoken to anyone about being in the institutions.

The confidential committee hearings were set up to allow survivors to describe their personal experiences in a non-confrontational way.

Anonymity was assured and their accounts and allegations were to be listened to without challenge.

Privacy was a concern for many witnesses and, given several said their pregnancies were a result of rape for which no-one was convicted, their testimonies were legally sensitive.

The Data Protection Commission said: "We have written to the commission with a number of questions around the deletion, and the legal basis for the deletion, of these records.

"We are awaiting their response."

When asked about the deleted recordings, the inquiry told BBC News NI it had explained the matter in its final report.

"Witnesses were asked for permission to record their evidence on the clear understanding that the recordings would be used only as an aide memoire for the researcher when compiling the report and would then be destroyed," the report stated.

Protests

Before it is dissolved, the inquiry must hand over its archives to the Department of Children.

Controversy about access to records first arose last year when survivors protested over reports the documents would be passed to the National Archives, where they could be sealed for 30 years.

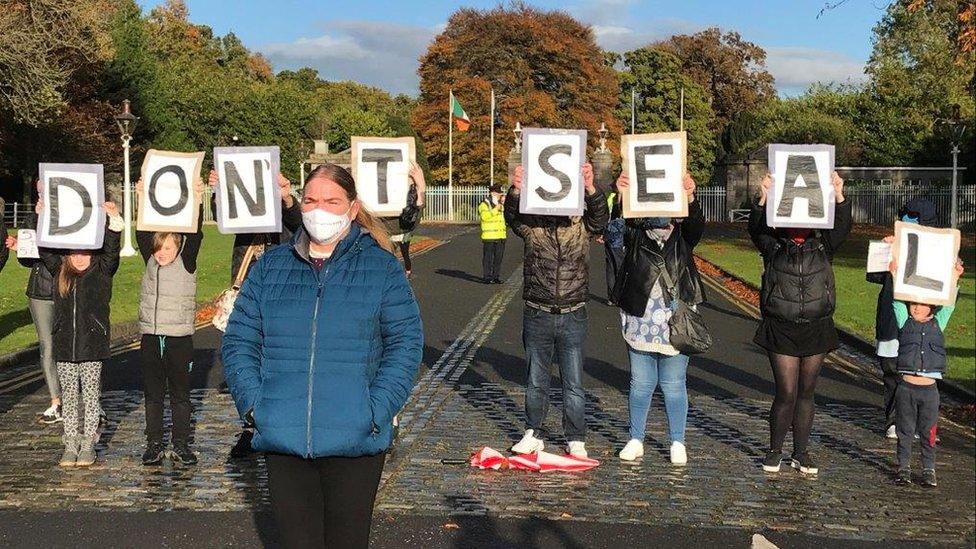

Campaigners held a protest last October over future access to the commission's records

At the time, the government insisted urgent legislation was required to protect the information from having to be destroyed or redacted when the commission was dissolved.

Since then, campaigners have disputed several of the inquiry's findings and called on witnesses to demand their own records before it is dissolved.

Lack of access to personal information is a particularly raw point for Irish adoptees, who are still not entitled to access their original birth certificates or identifying information on their biological family.

Ms Malone was adopted at 10 weeks old but as a young adult she managed to trace and eventually meet her birth mother.

Clodagh Malone was adopted 10 weeks after her birth

For the past 11 years, she has helped other adoptees trace their birth families but it can be a struggle accessing even basic details.

"For adopted people and I suppose birth mothers, everything - even down to our time of birth which means nothing to other people - is so important to us," Ms Malone explained.

She insisted that testimonies given by witnesses to the inquiry "belong to us" and survivors should be entitled to access their own information.

Children's Minister Roderic O'Gorman will receive the inquiry's archive at the end of this month.

He recently met the Data Protection Commission to discuss how future requests to access the sensitive material should be dealt with.

"In October 2020, the government passed legislation, explicitly providing for the protection of records of the commission and that they should be handed over to the department unredacted," Mr O'Gorman's spokesman told BBC News NI.

"Intensive preparations are ongoing prior to transfer of the archive to ensure subject access requests can be processed in full compliance with the data protection regulatory framework."

Despite the tight timeframe, he said there was "currently no proposal" to extend the 28 February deadline.

Related topics

- Published13 January 2021

- Published13 January 2021

- Published12 January 2021