Paris Commune: The revolt dividing France 150 years on

- Published

The Paris Commune lasted until late May 1871, culminating in a so-called "bloody week"

Exactly 150 years after the Paris Commune, rival passions are flaring again over how to remember the city's brief and much-romanticised experiment in power to the people.

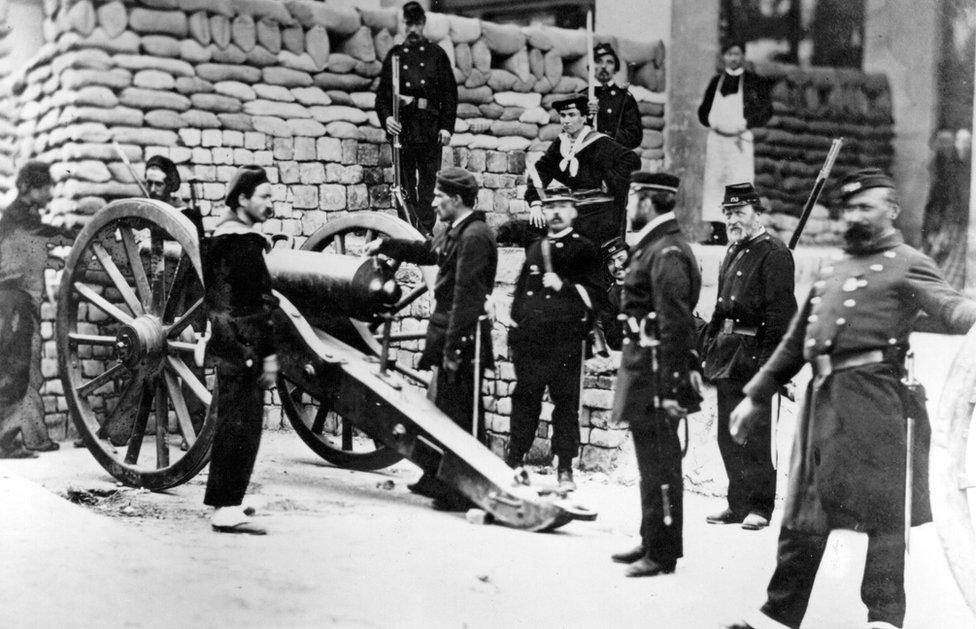

The first act of the city's famous insurrection came on 18 March 1871, when crowds stopped troops from requisitioning cannons parked on the hill of Montmartre. It was the aftermath of the siege of Paris by the Prussians, in which working folk had suffered terribly.

Over the next three months, people's committees ran the capital while the official French government fulminated in Versailles. But in May the army moved in and the Commune was crushed.

Soldiers eventually crushed the Commune after three months

For supporters then - and since - it was a springtime of hope bloodily repressed by the forces of conservatism. Karl Marx saw it as a prototype of his workers' revolution; Lenin was interred with a Communard flag as his shroud.

But for the right, it was a time of chaos and class vengeance. They remembered the killings of priests and the burning of landmarks like the Hôtel de Ville. Afterwards they atoned by building the Sacré Coeur church where the cannons had been.

A century and a half on, the Commune continues to divide.

For three months from today, Paris's left-run city hall has prepared commemorations focusing on what it sees as the movement's great social advances: equality for the sexes, disempowering the Church, participative democracy.

Paris City Hall has highlighted the social advances made by the Communards

But the right-wing opposition says that Socialist mayor and presidential hopeful Anne Hidalgo is "instrumentalising history" for political ends.

"You can summarise the Commune in one word: violence," says Rudolph Granier, a member of the centre-right Les Républicains (LR) on the city council.

"It was a populist movement. And in the current state of France and the world - when in Paris we have the yellow vests and in Washington they're storming the Capitol - I do not think we should be celebrating people who burned down our city hall."

For many centre-right politicians, Mayor Anne Hidalgo is using the anniversary for political ends

For another LR councillor, Antoine Beauquier, "the left-wing majority is doing its usual thing of mixing up history and politics".

"Of course there was an event called the Commune which we should remember. But we should remember what it actually was - not the fantasy of the Communist Party (PC). They think every Communard was a hero. But many were also killers."

According to the right, by allowing them to run the Commune commemorations Anne Hidalgo is throwing her PC allies a bone in the hope that they'll support her in the race for the French presidency next year.

The left has retorted by accusing the right of being "sectarian" and failing to see the justice behind the Communards' cause.

"It is a sign of the times - the French right is getting more and more hardline," says Laurence Patrice, Communist deputy mayor of Paris.

"They never used to care that much about the Commune. But now with Emmanuel Macron, the French have a president who has abandoned his centrism and is in fact more and more right-wing.

"And that is forcing the traditional right into positions that are ever closer to the extreme."

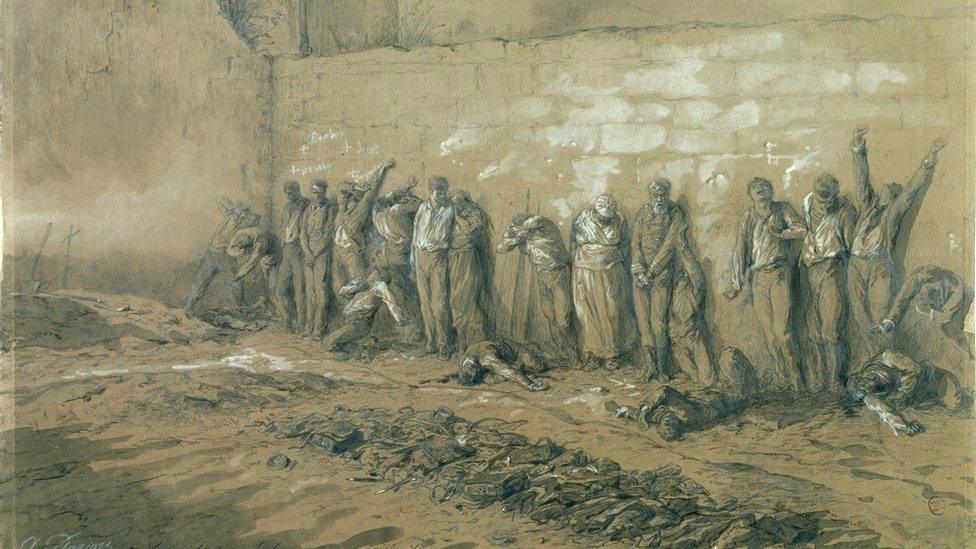

The Mur des Fédérés was the scene where many thousands of Communards were executed

In the so-called "bloody week" at the end of the Commune, thousands of supporters were summarily executed - many at the Mur des Fédérés (Wall of the Fighters) in Père Lachaise cemetery, which will be the focus of commemorations in May.

Thousands of others were imprisoned or sent into exile before being given an amnesty in 1880. An association, the Friends of the Commune, was set up then to help the returnees and exists to this day, its purpose now to keep alive the movement's ideals.

An illustration by Alfred Henri Darjou shows some of the Communards shot at the Wall of the Fighters

"Most revolutionary regimes that succeed end up disappointing," says the British historian of France Robert Tombs.

"Here was a revolutionary movement that didn't succeed, that didn't last that long. And therefore people are free to project on to it all sorts of things that might have happened and would have been good.

"So it's become an icon of feminism, secularism, of popular democracy. What it would actually have turned out as had it succeeded, we will never know."

More stories from Hugh

One hundred years after World War One, the village of Fleury-devant-Douaumont is a ghost town