Vatican laws changed to toughen sexual abuse punishment

- Published

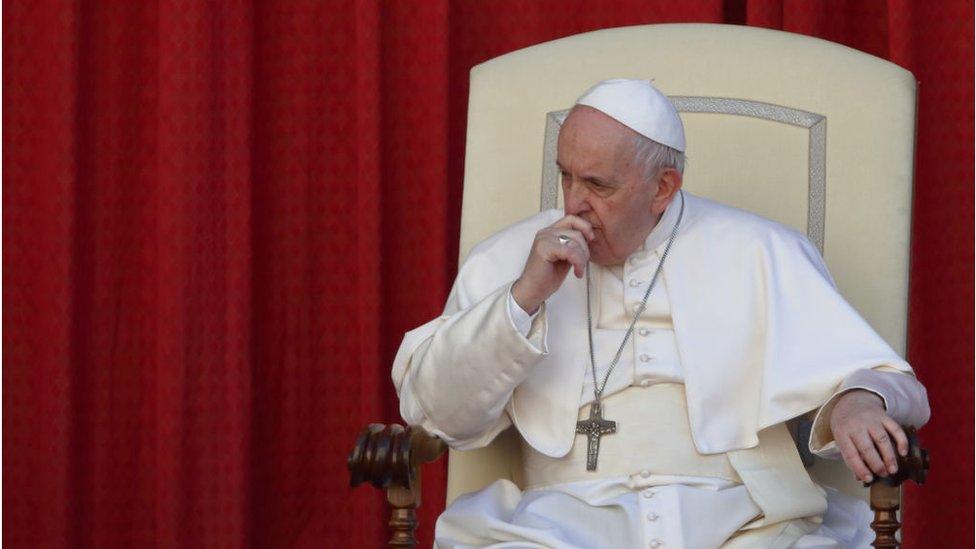

Pope Francis has changed the Roman Catholic Church's laws to explicitly criminalise sexual abuse.

It is the biggest overhaul of the criminal code for nearly 40 years.

The new rules make sexual abuse, grooming minors for sex, possessing child pornography and covering up abuse a criminal offence under Vatican law.

The Pope said one aim was to "reduce the number of cases in which the... penalty was left to the discretion of authorities".

The changes to the Code of Canon Law took 11 years to develop and included input from canonist and criminal law experts.

The Catholic Church has been rocked in recent years by thousands of reports of historic sexual abuse by priests, and cover-ups by senior clergy, around the world.

Victims and critics had complained for decades that the previous laws were outdated, designed to protect perpetrators and were open to interpretation.

The new code replaces the last major changes made by Pope John Paul II in 1983. It is designed to have clearer and more specific language, and dictates that bishops must take action when a complaint is made.

The new rules come into effect on 8 December. They also prohibit the ordination of women, recording confessions and committing fraud.

What are the changes?

The Vatican's law also now recognises that adults as well as children can be victimised by priests who abuse their authority. Previously, the Church believed adults could give or withdraw consent because of their age, and did not take into account that adults could also be victims, especially if there is a power imbalance.

The code says a priest can lose their position if they used "force, threats or abuse of his authority" to engage in sexual acts.

Brigitte, a survivor of child sex abuse by a chaplain, explains why she is ready to speak now (From 2019)

For the first time, laypeople working within the Church system, such as administrators, can also face punishment for abuse, such as losing their jobs, paying fines or being removed from their communities.

The new rules criminalise "grooming" of minors or vulnerable adults to pressure them to take part in pornography. It is the first time the Church has officially recognised grooming as a method used by sexual predators to exploit and abuse victims.

The law has also taken away the discretionary power that had previously allowed high-ranking Church officials to ignore or cover up allegations of abuse to protect priests. Now, anyone found guilty of this could be charged with negligence in failing to properly investigate and punish sexual predators.

Monsignor Filippo Iannone, who leads the Vatican department that oversaw the changes, said there had been "a climate of excessive slack in the interpretation of penal law", where mercy was sometimes put before justice.

The sixth commandment

The changes come under the new heading of "offences against human life, dignity and liberty," which replaces the previously vague "crimes against special obligations".

The new laws do not spell out sexual offences against minors, but instead still refer to offences against the sixth commandment, which prohibits adultery.

Advocates have long demanded the Church remove the reference to the sixth commandment, and define the abuse as a crime against children instead of a violation of priestly celibacy.

"Describing child sexual abuse as the canonical crime of 'adultery' is wrong and minimises the criminal nature of abuse inflicted on child victims. A canonical crime relating to child sexual abuse should be clearly identified as a crime against the child," said a 2020 report into child sexual abuse, external, sponsored by the UK government.

Pope Francis has worked to tackle sexual abuse allegations involving Catholic priests since he became pontiff in 2013.

He led a landmark summit on clerical sex abuse in 2019, and lifted the controversial rule of "pontifical secrecy" in a bid to improve transparency.

The Church previously shrouded sexual abuse cases in secrecy, in what it said was an effort to protect the privacy of victims and reputations of the accused. Critics said some Church officials abused the rule to avoid co-operation with police in abuse cases.

- Published22 September 2012

- Published24 May 2021