Belarus crackdown fails to crush opposition spirit

- Published

Two top dissidents - Maria Kolesnikova and Maxim Znak - went on trial on 4 August

Maria Kolesnikova has spent the past 11 months in a tiny cell, only allowed out for an hour's exercise each day. But when the opposition activist appeared in court this week, she was dancing.

Together with fellow activist Maxim Znak she's been declared a threat to national security and accused of plotting to seize power.

But as their trial began on Wednesday, Maria Kolesnikova was defiantly cheerful, smiling broadly at state TV cameras and making heart-shapes with her hands from inside a cage surrounded by armed guards.

Ahead of the hearing, Maxim Znak told the BBC that he is innocent and argued that closing the trial, supposedly for security reasons, underlines that.

'I didn't do anything,' he wrote in an exclusive interview from prison. 'There is only one reason to hide supposedly criminal public calls from the public (and from me too, so far) - and that's that they don't exist,' Mr Znak said.

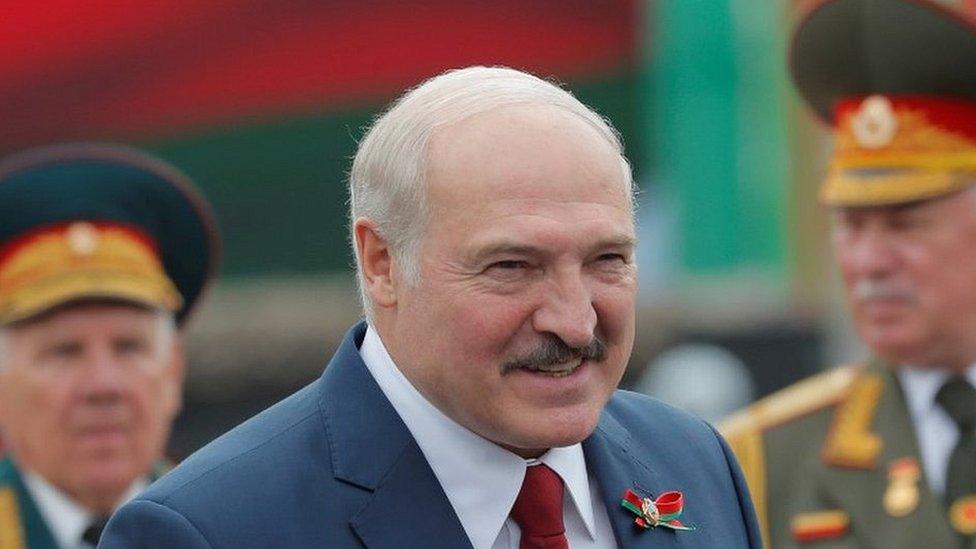

The pair are among the most high-profile figures to face trial since last summer's disputed presidential elections sparked street protests on a scale never seen before in Belarus. One year on, the authoritarian Alexander Lukashenko remains in power - under Western sanctions, but supported by Russia - and the streets have been cleared of demonstrators.

For weeks last year police fought running battles with protesters in Minsk

Outside Minsk regional court, family and friends gathered beside a police barrier blocking the entrance. Plain-clothed officers watched from nearby cars but there were no obvious riot police: the authorities clearly weren't expecting a crowd.

Maria Kolesnikova's father arrived with flowers for his daughter that he had to pass on via her lawyer as no-one else was allowed inside.

Spotting Alexander, a pro-regime blogger taunted him on the low turnout.

"There's no one here, no one cares about Maria," she crowed, trying to provoke him and capture it on camera.

But fear has stopped the protests, not indifference.

Maria Kolesnikova's father arrived outside the court with flowers

Maxim Znak's sister told me the clampdown on opposition, all criticism, is so severe now, many of her friends have left the country for safety.

"Big gatherings like we saw last year are impossible now," Irina argued. "It would just mean more people go to prison."

The human rights group Viasna already counts over 600 political prisoners in Belarus, including protesters, opposition activists and independent journalists. Even Viasna's own activists are in custody now.

More than 110 people are being held at a facility known as Valadarka, a 19th century castle in the very heart of Minsk with crumbling stone turrets.

"I've written around 4,800 letters, 100 stories, the sketch of a novel and a lot of poems and drawings," Maxim Znak wrote to the BBC of his time there, and his sister added that he was getting in shape by doing 20 press-ups for every letter that passed the prison censors.

He's working on a rock-opera in-between times.

"The aim is to isolate them," Dmitry Laevsky argued, saying the charges have "no basis".

The former lawyer represented Maxim Znak until he was disbarred a few weeks back; others who've worked with the opposition activists have lost their licence or face prosecution themselves.

"As we see it, someone does not want the ideas and opinions voiced by Maria and Max in the summer of 2020 to be spoken. So they chose to have them locked up," Mr Laevsky believes.

Nadezhda Znak (R) ,the wife of Maxim, has signed up to his official defence team

Maxim's Znak's wife is a lawyer like him, so she's signed up to his official defence team and is allowed to visit. But Maria Kolesnikova's father hasn't seen his daughter since her detention.

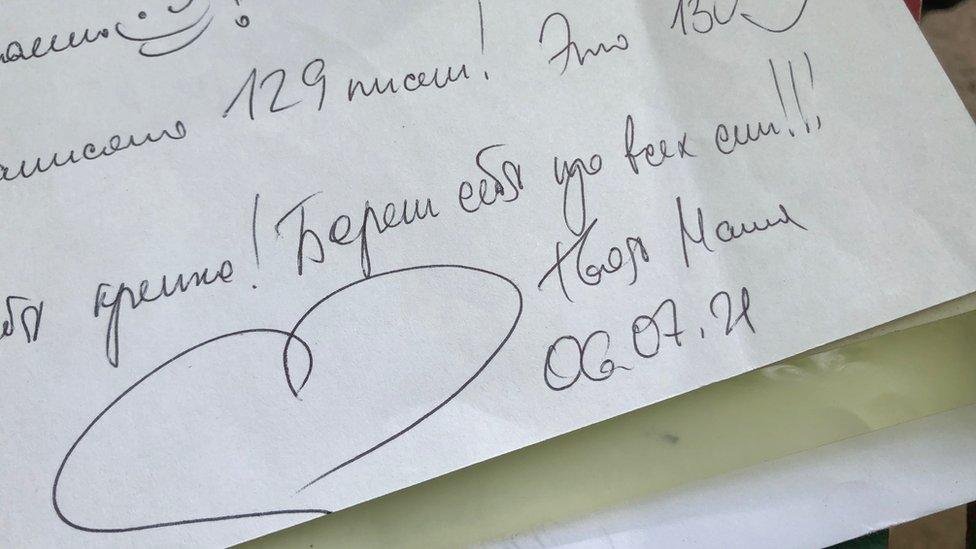

She writes every day from prison, pages covered in smiley faces and love hearts, and her positive energy is keeping Alexander from despair. He even admits to feeling guilty whenever he feels sad, because Maria is so determined to stay upbeat.

"Her lawyers say she laughs loudly even when she walks through the prison towards them," Alexander said. "Sensing her mood makes things a lot lighter for me, too," he confided.

Belarus: The basics

Where is Belarus? It has its ally Russia to the east and Ukraine to the south. To the north and west lie EU and Nato members Latvia, Lithuania and Poland.

Why does it matter? Like Ukraine, this nation of 9.5 million is caught in rivalry between the West and Russia. President Alexander Lukashenko has been nicknamed "Europe's last dictator" - he has been in power for 27 years.

What's going on there? There is a huge opposition movement demanding new, democratic leadership and economic reform. The opposition movement and Western governments say Mr Lukashenko rigged the 9 August election. Officially he won by a landslide. A huge police crackdown has curbed street protests and sent opposition leaders to prison or into exile.

Even so, the activists' families are braced for a long prison sentence: up to 12 years.

Their hope is that the pair won't actually serve all that: either political change will somehow come to Belarus or the pain of international sanctions will force President Lukashenko into a deal with the EU that includes the release of prisoners.

Maria writes letters filled with positivity and love hearts every day from prison

But no quick solution is in sight.

"It seems that someone thinks funding the repressive machine…is a lesser evil than observing the law and granting people their civil and political rights," Maxim Znak told the BBC.

"I think I've proved that changes are necessary in Belarus," he added. "As for the chances of that, everything's possible whilst we're alive."

Maria's letters to her Dad strike a similar tone, assuring him she'll be home soon. Everything will be OK, she writes, and Alexander is clinging to that - and the extraordinary images of his daughter dancing behind bars in court.

"That shows how free she still feels inside," he smiled, watching the video on his mobile phone. "I just wish I could actually see her," Alexander said, "and make that same heart shape back."

- Published6 August 2021

- Published6 August 2021

- Published27 May 2021

- Published2 June 2021

- Published3 August 2021

- Published11 September 2020

- Published23 August 2020

- Published1 December 2020