Tuam babies: Bill to excavate mass grave is 'healing moment for survivors'

- Published

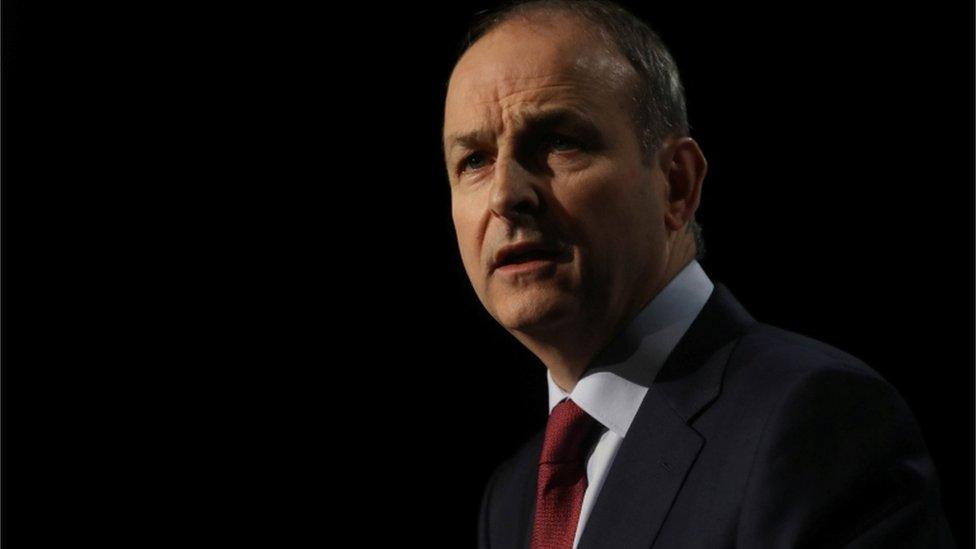

Catherine Corless was instrumental in exposing the story of secret burials at the Tuam mother and baby home

The local historian whose personal research helped uncover the Tuam babies scandal has said a new law to exhume the mass grave was a "healing moment".

Catherine Corless exposed the secret burials of children at a former mother and baby home in Tuam, County Galway.

By 2013, she found death certificates of 796 children who had died of various causes in the home but who had neither burial records nor marked graves.

On Tuesday, the Irish government agreed draft legislation to excavate the site.

If passed, the bill will allow children's remains to be exhumed and, where possible, identified and returned to relatives.

Reacting to news of the legislation, Ms Corless told BBC's Good Morning Ulster programme it was "a message to Ireland and further afield that this was wrong and it's a healing moment for survivors that our government cares enough to look after the survivors."

"The fact that such an atrocity could have happened and been covered up."

Tuam residents built a shrine decades ago ago in memory of all those who were buried in unmarked graves

Hundreds of children died in the Tuam mother and baby home over a 36-year-period.

Media coverage of Ms Corless' findings in 2014 suggested the possibility that some of the children may have been buried in an underground sewage tank.

Public outrage over the claims led the Irish government to set up a commission of investigation into mother and baby homes.

That inquiry later confirmed that a total of 3,251 children were either born in or were admitted to the Tuam home during its period of operation, 802 of whom died of various causes while they were inside the home - almost a quarter of all Tuam's child residents.

In 2017, test excavations carried out on behalf of the commission discovered the remains of several children's in a mass grave in a underground tank.

Two years later, the commission confirmed the chambered structure containing the children's remains was in a disused sewage tank.

A housing estate was built on the site after the Tuam home was demolished

Speaking on Thursday, Ms Corless said the draft legislation has been broadened to allow remains to be returned to relatives such as first cousins, nieces and nephews, whereas a previous draft bill was confined to immediate family members.

"So there will always be somebody connected to the babies in the sewerage facility," she said.

She said some DNA samples of remains have been taken..

"A lot are where they were put down, so they were quite happy that quite a lot of them will be recognisable through DNA," she said.

She said that after speaking to survivors and families over the years "their one wish" was to "give back that little baby to their mother - to bury their remains in the mother's plot, that is a huge issue with them".

"There will be an angels' plot for the babies who are not identifiable, perhaps in Tuam in the graveyard, where they should have been put in the first place."

Tuam residents built a shrine decades ago ago in memory of all those who were buried in unmarked graves

Tuam babies scandal

The Tuam home was run by a order of Catholic nuns, the Sisters of Bon Secours. It housed unmarried mothers and their children from the mid-1920s until it finally closed its doors in 1961.

But controversy over the fate of the hundreds of children who died while resident in the home made international headlines in 2014, when it became known as the Tuam babies scandal.

Mother and baby homes were usually overcrowded with poor infection controls and the commission found many Tuam deaths were due to diseases like TB, flu, gastroenteritis, meningitis and measles.

Despite a six-year investigation, the commission was unable to locate burial records or official graves for most of those children.

But it did carry out test excavations on the site and in March 2017 the commission confirmed its experts had discovered "significant quantities" of human remains in a underground structure at Tuam.

Sample tests confirmed that they were the remains of children ranging in age from premature babies to toddlers, most of whom died in the 1950s.

Related topics

- Published22 February 2022

- Published13 January 2021

- Published13 January 2021