Ukraine: Nick Robinson on how Germany is reversing decades of closer ties with Russia

- Published

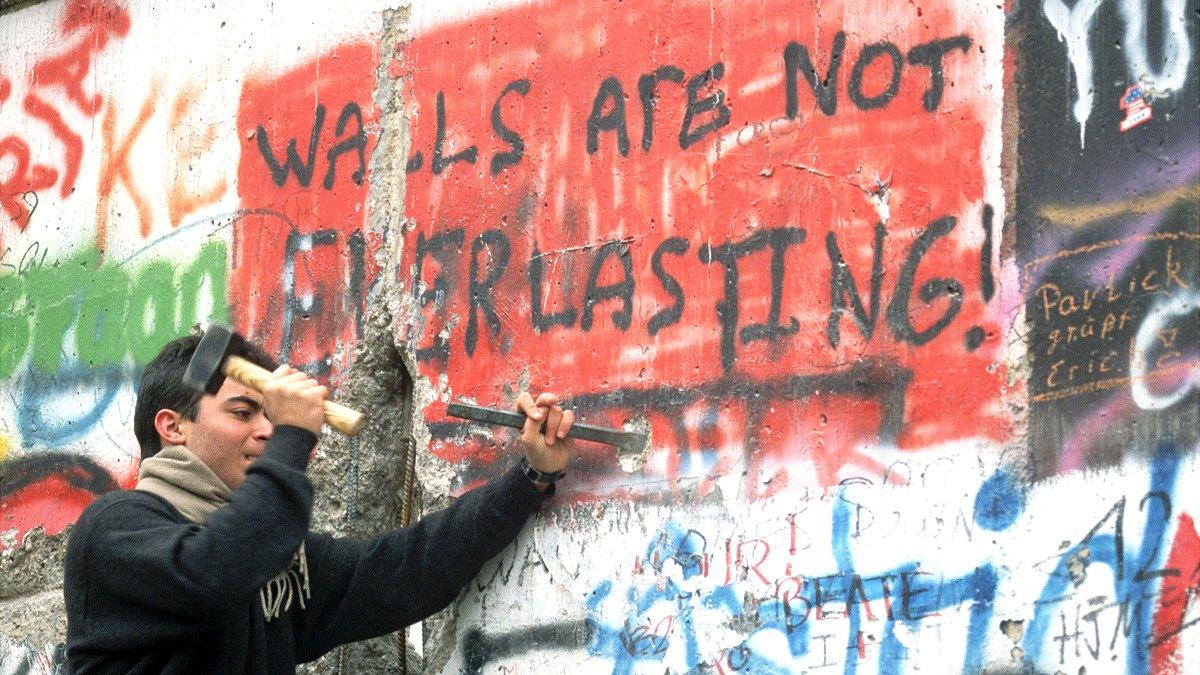

"Walls are not everlasting" read graffiti on the Berlin Wall in 1989

Just over three decades ago I stood on top of the Berlin Wall which - for almost three decades before - had torn friends and families apart, split a country and set the division of Europe in concrete.

I watched and held my breath with thousands of others on that heady night in November 1989, when one brave young man dared to jump off the wall into what had been "no man's land".

Days earlier he would have been shot, joining all those who had paid with their lives for daring to try to bridge the gap between East and West. Not on the night the wall fell. He held out a flower to a bewildered-looking East German soldier who, after a pause that seemed to last a lifetime, held out his hand and accepted the gesture of peace. The crowd lining the wall cheered wildly.

They - we - dreamt that Europe might now be "free and whole". People might soon be free to choose who governed them - whether they lived in Berlin or Prague, Warsaw or Budapest and perhaps, just perhaps, in Moscow and St Petersburg too.

I am back in Berlin - a city facing up to the fact that that dream is now dead thanks to Vladimir Putin's decision to invade Ukraine and to bomb its people into submission.

Germany's leader, Chancellor Olaf Scholz, spoke of this being a historic turning point. In German they have a word for it (they have a word for everything). It is zeitenwende.

Mr Scholz announced his country would now offer real military aid to Ukraine.

A few weeks before, his government had been mocked for its offer of 5,000 helmets to equip the Ukrainian army. The head of the German navy had to resign after he observed that all Mr Putin wanted was respect and that he probably deserved it.

German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, 9 March

The German chancellor has now pledged to spend more - €100bn (£84bn) more - on defence. What that means is that this country will soon become the biggest military power in Europe and the third biggest in the world - behind only China and the United States.

Not so very long ago, that prospect would have been greeted with fear abroad and protests at home.

As a young man - a member of what he calls "the 1989 generation" - Nils Schmid studied in Ukraine in what was then part of the Soviet Union. These days, he is a German MP and foreign affairs spokesman for the governing Social Democrats. He told me he and his fellow countrymen and women now had to accept that the "iron curtain" which divided Europe had simply moved.

Once it had stood a few hundred yards from his office. Now, long after the fall of the wall, it is on the border between Nato countries - whose defence is guaranteed by the US - and those who look to Moscow.

Opposite his office stands the vast Russia embassy - in what used to be East Berlin. It is now protected by police and there are barricades decorated with anti-war posters. A blanket lies on the ground and is filled with soft toys. The message to passers by is that it could be your children dying in Ukraine.

A "Freedom Square" sign in Ukraine's national colours in front of the Russian embassy in Berlin, 13 March

There, I met Michael - a biker from the Black Forest in south-west Germany. He was recording a video next to his Yamaha, which he had re-painted in the blue and yellow colours of the Ukrainian flag. He had ridden for eight hours carrying a folder bulging with 600 messages to Vladimir Putin - from friends, neighbours and colleagues calling on the Russian president to stop the war.

The embassy staff had refused to accept it. Michael had come to realise that talking to Russia (what used to be called detente) was not enough. Germany now had to be prepared to confront Moscow.

What that means is the children of that 1989 generation will not enjoy the same freedoms as their parents. They will not grow up believing that wars are what happened in the past. Indeed a recent poll showed that seven in 10 Germans fear the spread of this war.

People from Ukraine queuing for mobile phone cards in Berlin, 14 March

And no wonder. The refugees driven from their homes by this conflict are pouring off trains into Berlin's stations at a rate of, some say, 10,000 a day.

This war is re-shaping how Europe's most powerful country thinks. That will have dramatic consequences which are only just beginning to be thought through.

You have to be almost 40 years old to remember the day when the wall fell back in November 1989. These days of February and March 2022 are turning out to be just as consequential.

War in Ukraine: More coverage

- Published14 March 2022

- Published10 March 2022

- Published5 March 2022

- Published27 February 2022