Why the Red Cross has to be neutral in the Ukraine conflict

- Published

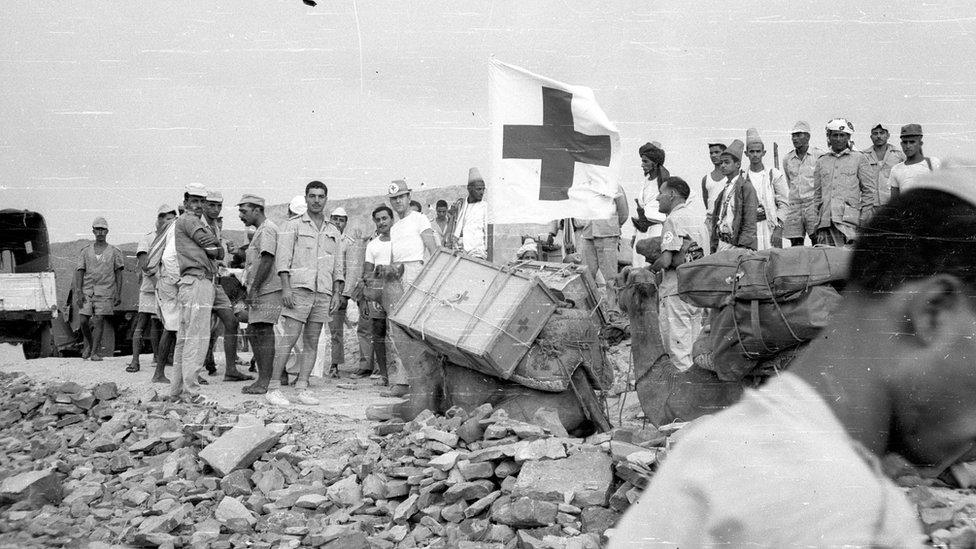

The ICRC has been working in eastern Ukraine since the conflict there started in 2014

The International Committee of the Red Cross has condemned what it calls a "widespread and systematic campaign of misinformation" about its work in Ukraine.

These are strong words from the famously neutral organisation, and reflect deep concern that its humanitarian operations worldwide could be undermined by what appears to be a co-ordinated strategy designed to destroy trust.

"It is a targeted deliberate campaign, discrediting the ICRC and its work. It's unacceptable," said the organisation's director general, Robert Mardini.

For at least two weeks, across multiple social media platforms, criticism and false accusations against the ICRC have been appearing, in Ukrainian and in Russian. One of the most damaging is the claim that the organisation has supported "forced evacuations" of Ukrainian citizens across the border into Russia.

Robert Mardini is the director general of the ICRC

Mr Mardini said this was absolutely not correct.

"The rules of war say that civilians must be protected everywhere, where the conflict is happening, and when they choose to leave because the situation is untenable, it should be of their own free will," he said.

Communication with both sides

Another focus of criticism has been ICRC President Peter Maurer's visit to Moscow, where he was pictured shaking hands with Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov. For some in Ukraine, the optics may not be ideal, but Mr Maurer was in Kyiv before he was in Moscow, and he shook hands there too.

Peter Maurer (left) shook hands with Russia's foreign minister Sergei Lavrov on his recent trip to Moscow

The ICRC is the guardian of the Geneva Conventions; the only side it will ever take in a conflict, says Mr Mardini, is the side of civilians, the wounded, prisoners of war, and the rules of war themselves.

Russian and Ukrainian mothers want to know the fate of their sons; if they are prisoners, they want to know where they are, and they want to write to them. If they are dead, they would at least like to be able to bury them. In war, it's the ICRC's job to facilitate this.

Peter Maurer went to Kyiv and Moscow to urge both sides to co-operate in sharing information about the dead and about prisoners.

"These are concerns that should transcend politics," said Robert Mardini. "These are the basics of humanity."

Why not speak out?

But Peter Maurer also went to Moscow to urge humanitarian access to besieged Ukrainian cities such as Mariupol. Under the Geneva Conventions, civilians have a right to the basics of life: food, water, medical care. They also have a right to leave a conflict zone safely if they want to.

So far, despite repeated appeals from both the Red Cross and the United Nations for humanitarian corridors, this hasn't happened.

Families huddled, cold and hungry, in Mariupol's cellars may be angry that the guardian of the Geneva Conventions has not publicly lambasted the Russian army for not respecting those conventions.

The ICRC is the guardian of the Geneva Conventions

But public dressing downs are not the ICRC's style. Way back in 2004, when hideous pictures of US soldiers abusing Iraqi prisoners in Abu Ghraib prison emerged, it became clear the ICRC had known about this abuse for some time. Rather than going public with its evidence, it chose to continue quiet diplomacy with Washington, and continue regular visits to Abu Ghraib.

"We're not some dial-a-quote organisation," an ICRC officer told me at the time, "there are human rights groups for that."

Preserving access to civilians suffering in war zones, to detainees and prisoners of war, is the ICRC's number one priority. Its strategy is to explain the rules of war to the warring parties privately, but not to go running to the media when it learns violations are taking place. That, the argument goes, could put an end to the access.

'Time is running out'

But there are exceptions. During the war in the former Yugoslavia, the ICRC denounced the "detention and inhuman treatment" of innocent civilians. In Rwanda, while refraining from using the word genocide, its delegates in the field made public statements about "systematic carnage", and "the extermination of a significant portion of the civilian population."

And in Ukraine, the ICRC's latest statement says "the level of death, destruction and suffering that continues to be inflicted on civilians is abhorrent and unacceptable." For civilians in Mariupol, Robert Mardini worries, "time is running out".

The ICRC has operated in many conflicts around the globe

The task now though will be to ensure that trust in the ICRC's work is not damaged further. It remains unclear who is behind the campaign of misinformation, but the ICRC is convinced it is targeted and deliberate.

This week the office of the Ukrainian Red Cross was hit by a Molotov cocktail. The ICRC and its local Red Cross and Red Crescent partners are not armed, and they never travel with armed guards. Their protection, Robert Mardini says "is the red cross".

He points to what the ICRC can do, when trust is there: prisoner exchanges in Yemen, the release of kidnapped Nigerian school girls, the safe evacuation of civilians from Aleppo.

"We need to ensure we are perceived as neutral and impartial. This neutrality, international humanitarian law, when it works, it does save lives.

"At the end of the day, this, the rules of war, is the frontier between barbarism and humanity. So we will always keep pushing for this."

War in Ukraine: More coverage

Related topics

- Published28 March 2022

- Published29 March 2022