Ukraine war: Kyiv's battle for justice over alleged Russian war crimes

- Published

Ten victims - some completely charred - were discovered in one mass grave in Bucha

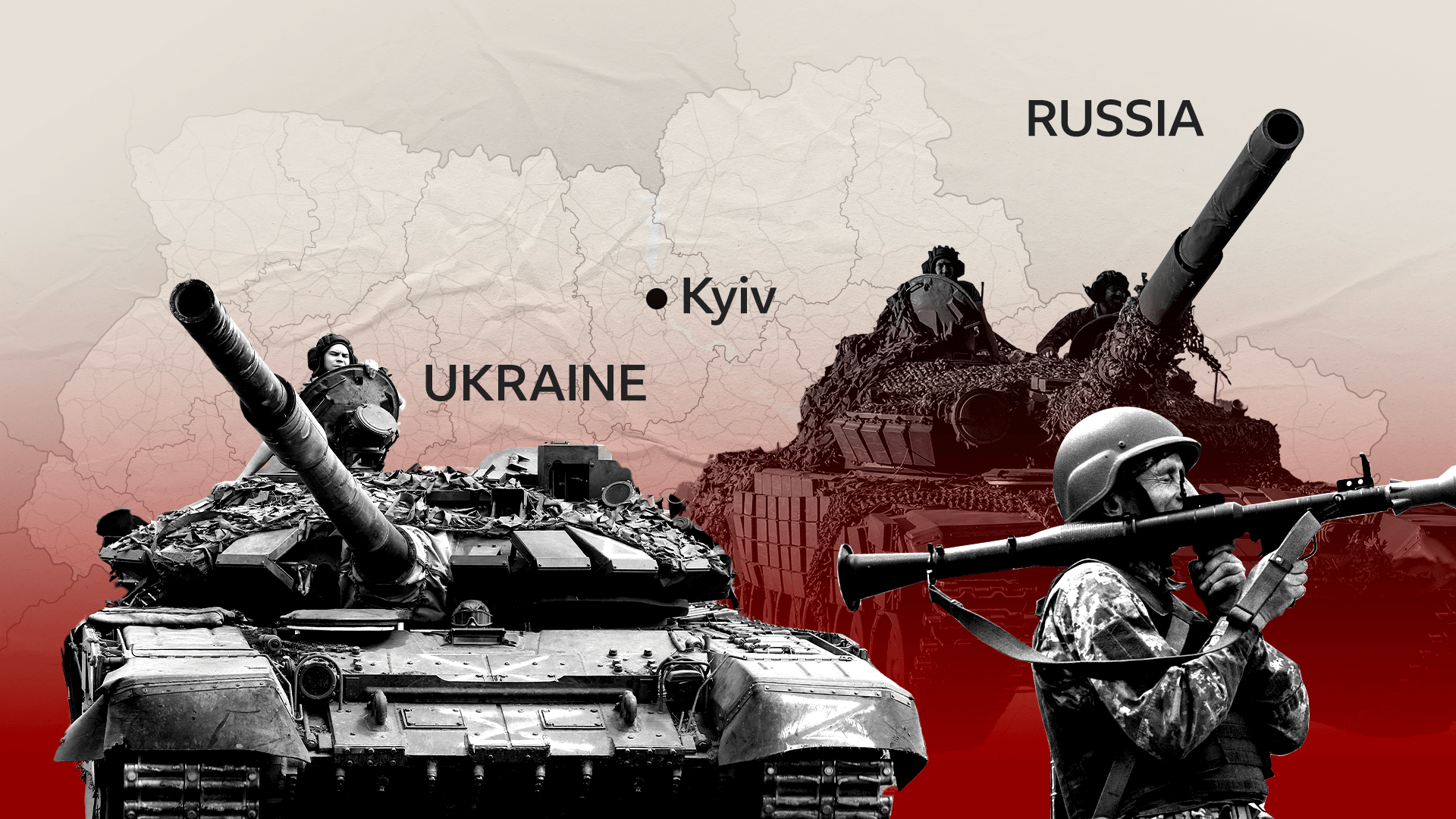

Ukraine's fightback against Russian aggression is not just in the battlefield - but in the legal field too.

Across this shattered country, testimony is being gathered and evidence collated for a goal that may only come long after the guns fall silent - international justice.

The pursuit of it is being led by Ukraine's Prosecutor General, Iryna Venediktova, appointed two years ago as the first woman to hold the office.

She watched the exhumation of another mass grave this week, beneath a gold-domed church in Bucha, where the darkest of sins were discovered - 10 victims this time, some completely charred. Their remains were placed into body bags and taken off for an attempt at identification.

As she stood at the edge of the deep pit, she told me more than 6,000 cases of war crimes have already been opened.

"A lot of people speak about the genocide of the Ukrainian people - and we actually have grounds to talk about genocide," she said. "Vladimir Putin is the president of the aggressor country killing civilians here in Ukraine. He's responsible."

The Kremlin continues to deny such allegations.

Iryna Venediktova says it's Ukraine's ultimate goal to see President Putin being prosecuted

The challenge for prosecutors will be to draw a direct line of responsibility from the top of the Russian state to the atrocities on the ground - and show that they weren't just committed but ordered.

Russia is not party to the International Criminal Court (ICC) in the Hague, having withdrawn in 2016. Nor, in fact, is Ukraine, although it does accept the court's jurisdiction for crimes committed within its territory.

The possibility of ever seeing President Putin himself in a tribunal is thought to be extremely slim.

But Ms Venediktova insisted it was her government's ultimate aim. "It's very important, not just for Ukrainians," she said, "it's important for the whole world to stop dictators."

The efforts of the Ukrainian state are being helped by a network of volunteer investigators, deploying across the country in a grassroots quest for justice.

Among them is an NGO called Truth Hounds, whose staff have been trained by former prosecutors from the ICC.

Borodyanka was virtually wiped out as a town by heavy Russian shelling

We followed them to the town of Borodyanka, some 50km (31 miles) north-west of Kyiv, which has been gutted by a month-long offensive and occupation.

The destruction is immense. Apartment blocks have been wrenched apart or blown open. Entire streets lie in ruins. And amidst the devastation of shattered glass and mangled metal lie the remnants of cluster bombs, whose use is banned under an international convention.

Roman Koval from Truth Hounds said they had gathered eyewitness accounts that the Russians gave orders to attack buildings once they were already in control here.

"They knew this city was full of civilians, with no combatants left, and they tried to raze it to the ground," he said.

The investigators' work, he added, went beyond documentation of attacks; it was one of establishing the truth - and of collective memory.

"We're trying not to let Russia formulate their lying narratives about the war in Ukraine," he said. "We're trying to show people that the war crimes that Russian troops are committing became a pattern of their behaviour, not just in Bucha or Borodyanka, but all over the occupied territories."

He picked his way through the ruins of an apartment belonging to Oksana and Nicola Laba, which was ravaged by the shock waves of an airstrike next door. Much of it has been reduced to rubble.

Oksana says that "Russia will not stop until it destroys our country"

Crouching amid the debris - fragments of broken glass covered any place to sit - he listened to their testimony and took notes. The details will be added to a central database as the war crimes case against Russia builds.

Oksana told of how her mother managed to flee just before the airstrike hit.

"Our home was our cosy nest, where we were planning our children's birthday," she recalled. "It's hard to describe our terror - it's more like hate."

Storytelling here carries with it the hope that accountability will be pursued.

"It's very important to say what happened," Oksana said, "because these are not just war crimes: Russia will not stop until it destroys our country."

On the scarred street outside, diggers have started to clear up the wreckage of homes and once-happy lives. The freedom and safety that Ukrainians cherished has been destroyed.

But their solace now would be to see - and believe - that there will be punishment for those who have broken this country.

Watch: Destruction in the Ukrainian town of Borodyanka

War in Ukraine: More coverage

ANALYSIS: Why Russia wants to seize eastern Donbas

ON THE GROUND: Collecting the dead in Bucha

READ MORE: Full coverage of the crisis, external

Related topics

- Published6 April 2022

- Published13 April 2022

- Published6 April 2022

- Published12 April 2022

- Published12 April 2022

- Published12 April 2022

- Published20 July 2023

- Published11 April 2022