France election: Marine Le Pen concedes election but still counts a win

- Published

Marine Le Pen: "I will never abandon French people"

So, the pariah did not become president. Marine Le Pen, with under 42% of ballots, didn't even reach the share of the vote she was predicted to.

And yet this result still counts as a win for her and her party, the National Rally, because of the unique political baggage they carry in France.

"I console myself by thinking: at least the time we spent leafleting wasn't wasted, because we were rewarded with a big result!" said Clement Turpin, a 20-year-old supporter from the northern town of Denain.

This was the best score the National Rally has ever had. It has only made it to the presidential run-off three times, and never won, though it has dramatically increased its score each time.

"If we gain 10 points every [presidential election]," the party's interim president, Jordan Bardella, told French television this morning, "next time, we'll win."

As supporters nurse their hangovers this morning, a question hangs in the air over National Rally headquarters in Saint-Cloud: what does the party do now?

"There is a kind of fatigue, from having excellent scores in the first round and being systematically beaten in the second," said Nonna Mayer, one of France's foremost experts on the far right. "There's certainly a form of demoralisation in the party, except within her closest circle."

Ms Le Pen has expanded her party's appeal over the past decade, tailoring her economic policies to reach struggling working voters disillusioned with the left. She's also spent years trying to soften her image and rid the National Rally of its toxic history, thanks to the anti-Semitism of her father and party founder, Jean-Marie Le Pen.

It's worked, in that her support has risen in this election. But, says Nonna Mayer, one of France's foremost experts on the far right, Marine Le Pen always faces the same limitations.

"The main one is the lack of credibility," Dr Mayer told me. "She's fuzzy on several items [of policy], she doesn't convey the image of a leader, and she's still seen as a danger to democracy by 50% of the population."

Will anyone with the name Le Pen ever be president in France? Some have questioned whether Jean-Marie has blocked the path to power for anyone sharing his surname. President Emmanuel Macron seems to think so: during the election campaign, he repeatedly referred to Marine Le Pen as the "heiress" of her family name and ideology.

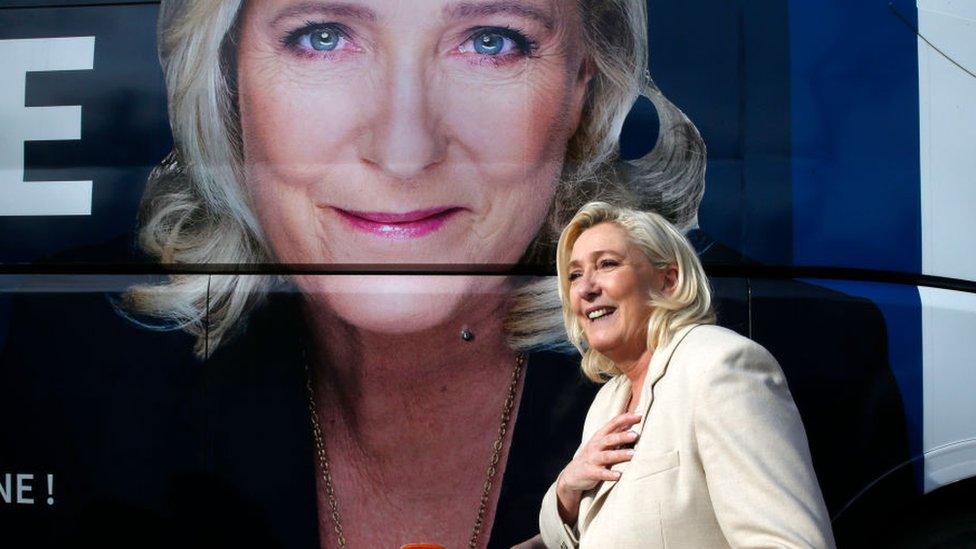

Even Ms Le Pen herself seems to agree: she's removed any mention of her surname or party name from campaign literature. On her posters and leaflets, she's now simply "Marine". Her initial "M" - which sounds like the word "love" in French when spoken - has sparked a new slogan-slash-pun: "Marine Le Pen" has become "M La France".

Vote Marine, the campaign said - but did not use Ms Le Pen's surname

"Many people think that the name 'Le Pen' is a stain," said supporter Clement Turpin. "A renewal is always good: it brings freshness, and new ideas. But in the deprived area where I live, 'Auntie Marine' is an institution."

But there are few figures in the party who are seen as natural replacements for its leader.

Ms Le Pen's niece, Marion, has already dropped her Le Pen surname and is popular with some supporters, but is currently banished from the party after switching her support to her aunt's nationalist rival, Eric Zemmour.

And the party's current acting president, Jordan Bardella, widely seen as Ms Le Pen's right-hand man, is articulate, politically slick and comes from the Paris suburbs - but is still only 26 years old.

Ms Le Pen said before this election that she would not run for president again. This morning, party officials have seemed unclear on what her plans are - or should be. Her name, it seems, is not the only problem.

Watch: Key moments from election night

"I'm sure the knives are out [for Le Pen], because they've been out for quite a long time," Nonna Mayer told me. "There's a very bad atmosphere in the party. Marine Le Pen is perceived as very authoritarian. There have been purges. The party is not in good shape."

"For me, it would be good if we could build a patriotic national camp with some of the people around [nationalist] Eric Zemmour, and [centre-right] Valérie Pécresse," said Clement Turpin. "We have some similar ideas."

An alliance with Eric Zemmour was floated early in this campaign but dissolved into animosity between the two camps.

Today, Jordan Bardella dangled the prospect again.

"It's a subtle marriage proposal!" he told France's BFMTV channel. "There is no alliance between parties as such, but we are in the process of creating a great pole of opposition to Emmanuel Macron's policies. And we want to support people who are not from the National Rally."

With parliamentary elections in June offering a fresh chance to challenge Mr Macron's power, the National Rally will be asking itself again whether an alliance, a new strategy or even a change of leader could help them break the glass ceiling that still hangs over the far right in France.

- Published24 April 2022

- Published25 April 2022

- Published25 April 2022

- Published22 April 2022