Ukraine war sees Swiss challenge their age-old neutrality

- Published

Protests against Russia's invasion of Ukraine have drawn crowds of tens of thousands across Switzerland

How does a European country stay neutral when war rages in Europe? Switzerland managed it during the first and second world wars, but now, watching Russia's attack on Ukraine, many Swiss are rethinking their long-established position.

Switzerland was granted "eternal neutrality" at the Congress of Vienna in 1815. It was a pragmatic, geopolitical move that was supported because the country was seen as a harmless buffer between Europe's big powers - France on one side, Austria and Prussia on the other - and it preserved Switzerland's safety while its neighbours slaughtered each other.

During World War Two, Swiss neutrality was more pragmatic than heroic. Switzerland mobilised all its able-bodied men to defend its borders, but it also banked gold looted by the Nazis and, in a shameful move designed to keep Germany at bay, turned away thousands of Jewish refugees - a policy it finally apologised for in the 1990s.

Nevertheless, gratitude for being spared two world wars is, says Markus Haefliger, politics correspondent with the Tagesanzeiger newspaper, "almost in our genes… that makes neutrality so important for Swiss people".

For decades, neutrality has enjoyed almost universal support among the Swiss - opinion polls have shown approval ratings of well over 90%. But now, says Mr Haefliger, the Swiss are soul-searching. "They ask themselves how can you stay neutral in a war like Ukraine? It's so clear who is the good guy and who is the bad guy."

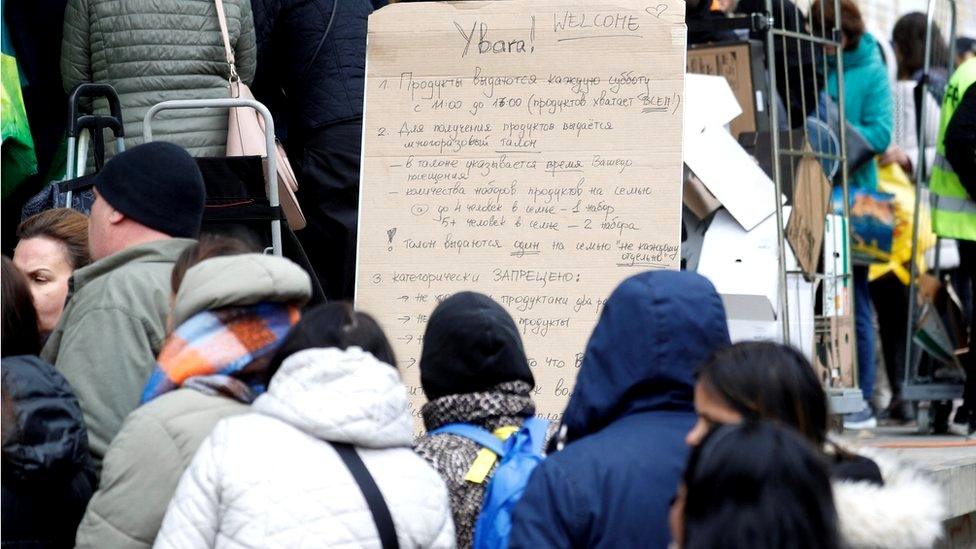

A sign points Ukrainian refugees in the direction of a food distribution centre in Zurich

Democracy versus autocracy

When Russia invaded its neighbour in February, thousands of Swiss citizens took to the streets, condemning the aggression and demanding support for Ukraine. Thousands also offered their homes to Ukrainian refugees, for whom the Swiss government has offered visa-free collective protection.

For young Swiss in particular, the idea that their country could stay aloof in such a conflict seemed unthinkable.

Operation Libero is a young, non-aligned political movement which campaigns for closer ties with Europe - Switzerland is not a member of the EU - and a less isolationist strategy. Its president, Sanija Ameti, believes this new war has been a wake-up call.

"Swiss people are realising that they are part of this European family of liberal democracies. This is a fight between systems, the one that we are in, and the autocratic, kleptocratic system of [Russian President] Putin."

We really need a debate about whether we have to protect our [democratic] system with weapons

That's a view shared by most political parties and most members of the Swiss government, which moved after a brief hesitation to adopt all the EU's sanctions against Russia. It's a big change from just 40 years ago, when - to the enduring shame of many Swiss - Switzerland did not join sanctions against apartheid South Africa.

The adoption of sanctions was greeted with headlines around the world, suggesting that Switzerland had abandoned neutrality. In fact, when it comes to sanctions, neutrality has been fraying round the edges for some time, says Stefanie Walter, politics professor at Zurich University.

"Switzerland has actually changed position quite a lot in the last couple of decades," she points out. It joined United Nations sanctions against Iraq in the 1990s, and those against former Yugoslavia. "And right now, as well as Ukraine, there are about 23 other sanctions in place."

Sanctions - but no tanks

But while sanctions may be supported by most Swiss, any military support appears at first out of the question. Switzerland's neutrality is legally defined by the Hague Convention of 1907, and forbids sending weapons to countries at war, as does Swiss domestic law on weapons exports, which was recently tightened.

And so when Germany asked Switzerland to permit the export of Swiss-made ammunition for tanks Berlin is sending to Kyiv, the Swiss said no. That move prompted criticism from a surprising source, when the leader of the centrist Die Mitte party tweeted, external that in his opinion it would be legitimate to send weapons in the defence of European democracy.

The type of ammunition manufactured for some Swiss tanks can also be used by tanks being sent to Ukraine by Germany

Other centrist politicians have suggested closer Swiss ties with the Nato military alliance, including a common air defence system and participation in the organisation's military exercises.

Such opinions would have been unimaginable just a few months ago, and they will be fiercely resisted by the right, where the Swiss People's Party is threatening a referendum to make even sanctions illegal, and on the left, where the Social Democrats and the Greens are opposed to any military involvement.

Goodbye neutrality?

But bit by bit, many Swiss are beginning to contemplate a new identity, and a new security strategy for their country.

A recent opinion poll showed that, while two-thirds of Swiss still opposed the idea of joining Nato, more than half (52%) were in favour of joining a European defence union.

This plan, known in Brussels as Pesco (permanent structured military co-operation) would involve countries committing to a common security and defence policy. Armies would work together, and fighter planes, tanks and other weapons would be jointly procured. The end goal: a common European army.

The idea of neutral, non-EU member Switzerland getting involved in something like this would have been unthinkable just a few months ago, but the war in Ukraine has clearly changed opinions.

I am really sure that Swiss neutrality will head somewhere different from where we have been, but I'm not sure where

Sanija Ameti believes Switzerland has a responsibility to defend European liberal democracy.

"We really need a debate about whether we have to protect our system with weapons," she explains. "The consequence would mean not being neutral anymore."

Prof Walter does not go quite that far but suggests that "Switzerland has to define neutrality anew".

For Markus Haefliger, the war in Ukraine has clarified Switzerland's position in a new, polarised world. "Switzerland is so clearly part of the Western world, its values, its economy, its traditions, everything," he says.

"The big question is, can we be neutral in the traditional sense in this new world order?"

Related topics

- Published29 March 2022

- Published3 May 2022

- Published26 January 2023