Is Nato's Nordic expansion a threat or boost to Europe?

- Published

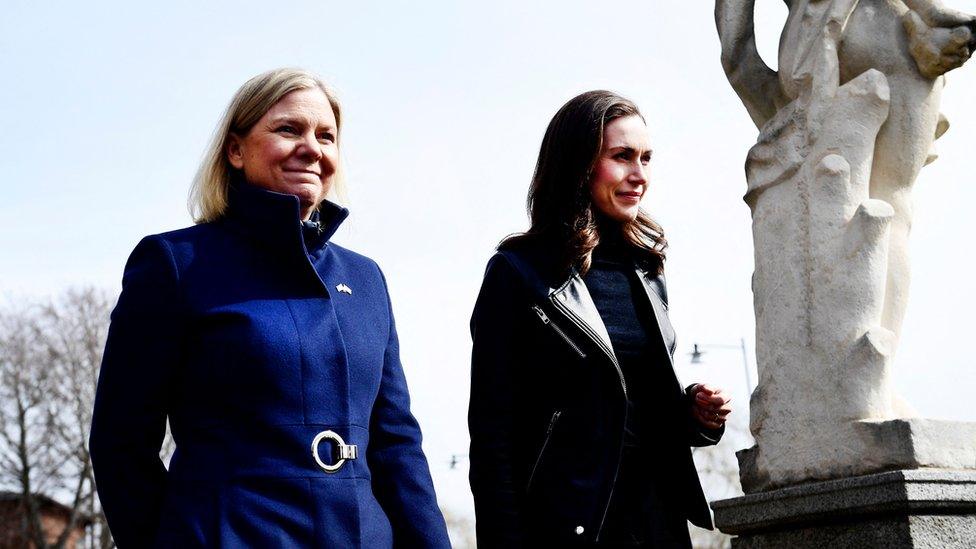

Swedish Prime Minister Magdalena Andersson and Finnish Prime Minister Sanna Marin at a meeting to discuss Nato membership

Finland and Sweden, two neutral Nordic countries, are so alarmed by Russia's invasion of Ukraine that they are both now seriously considering joining Nato, as early as this summer.

Russia has warned them not to. It has threatened "a military technical response" if they do.

So, on balance, is Europe a safer or more dangerous place if either or both of these countries become a part of Nato?

Nato - the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation - is a 30-nation defensive alliance founded shortly after the end of World War Two. It has its headquarters in Brussels but is dominated by the massive military and nuclear missile power of the US.

Finland and Sweden are both modern, democratic countries that fulfil the criteria for Nato membership. The organisation's chief, Jens Stoltenberg, has said he would welcome them with open arms and there would be minimum delay in processing their membership.

US Army Lt Gen (retd) Ben Hodges, who commanded all US land forces in Europe, is in no doubt of the benefits of this for the West:

"Sweden and Finland joining Nato is huge - a very positive development. They are two very strong democracies, and the military of both is very good, capable and modernised, with remarkable mobilisation systems."

In the case of Finland, a form of military integration is already under way. British tank crews recently went on exercise with a Finnish armoured brigade, together with US, Latvian and Estonian troops as part of Nato's so-called Joint Expeditionary Force (JEF). The UK's ministry of defence said the aim was to "deter Russian aggression in Scandinavia and the Baltic states".

So, what is the problem if either or both countries want to join?

Russia, and more specifically President Vladimir Putin, does not see Nato as a defensive alliance. Quite the opposite. He views it as a threat to Russia's security. He has watched in dismay as Nato steadily expanded eastwards - closer to Moscow - after the disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1991.

When Putin was a young intelligence officer in the Soviet state security apparatus, the KGB, Moscow controlled all the countries of eastern Europe, with Russian troops stationed in most of them. Today, nearly all those countries have opted to look westwards and join Nato. Even the Baltic states - Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania - countries that were once, unwillingly, part of the Soviet Union, have joined the alliance.

Only 6% of Russia's vast borders are with Nato countries, yet the Kremlin is feeling encircled and threatened. Shortly before President Putin sent his troops into Ukraine on 24 February, he demanded a redrawing of the security map of Europe. Nato troops, he insisted, should pull back from all of these eastern European countries, and no new countries should be allowed to join.

His invasion has now resulted in the opposite.

For decades, Finland and Sweden have carefully nurtured their neutrality. Culturally, they are firmly in the western camp, but until now they have been wary of antagonising their giant nuclear-armed neighbour, Russia. The Ukraine invasion prompted a radical rethink, with both government and people wondering if they might not be safer after all "inside the tent", sheltering under Nato's collective protection known as "Article 5". This views an attack on one member as an attack on all. A recent poll in Finland showed 62% of Finns in favour of joining.

The case in favour

From a purely military perspective, the addition of Finland's and/or Sweden's substantial militaries would be a major boost to Nato's defensive power in the north of Europe, where it is massively outnumbered by Russia's forces.

Finland, says Ben Hodges, brings F35 fighter jets, Sweden brings Patriot missile batteries and has re-secured its large Baltic island of Gotland, where Russia has recently been probing. The armed forces of both Finland and Sweden are experts in Arctic warfare, training intensively to fight and survive in the frozen forests of Scandinavia. When Russia invaded Finland in WW2, the Finns fought ferociously against the invaders, inflicting serious losses.

Geographically, the addition of Finland fills in a huge gap in Nato's defence, doubling the amount of its border with Russia. Security and stability in the Baltic Sea, says Hodges, are now dramatically improved.

Politically, it would add to the cohesion of western mutual defence, sending a signal to Putin that almost all of Europe is united against his invasion of a sovereign country, Ukraine.

The case against

Put simply, the risk here is that such a major expansion of Nato, right on Russia's doorstep, alarms and enrages the Kremlin so much that it responds by lashing out in some form. When Putin threatened to take "military technical measures" in response this, it is widely taken to be two things - a reinforcing of its own borders by moving troops and missiles closer to the West, and possibly a stepping up of cyber attacks on Scandinavia.

Staying neutral has served Sweden very well over the years. Giving up that neutrality is not to be taken lightly. There will also be an economic cost for Sweden's domestic arms industry if the country is obliged to buy Nato weapons instead of its own.

The Kremlin spokesman Dmitri Peskov was emphatic in warning that Finland and Sweden joining Nato "will not bring greater security for Europe".

Vladimir Putin likes to remind people of the time in his youth when he cornered a rat in a room and it turned on him in attack. Putin and his advisers already blame Nato, with some justification, for thwarting their plans to take over Ukraine. If they decide, unreasonably, that this sudden expansion on their northern flank presents an existential threat to Russia's security then there is no knowing exactly what Moscow could do in response.

War in Ukraine: More coverage