Ukraine war: Against the thud of artillery, miners struggle on

- Published

Imagine being a coal miner, descending into a deep, ageing, rickety mineshaft.

Then imagine doing that in a war zone.

"It's scary, but what can you do? We don't have many other options," said Ukrainian nurse Ira Yusko, 30, smiling grimly, as she switched on her headlamp at the Toretsk coal mine in the eastern Donbas region.

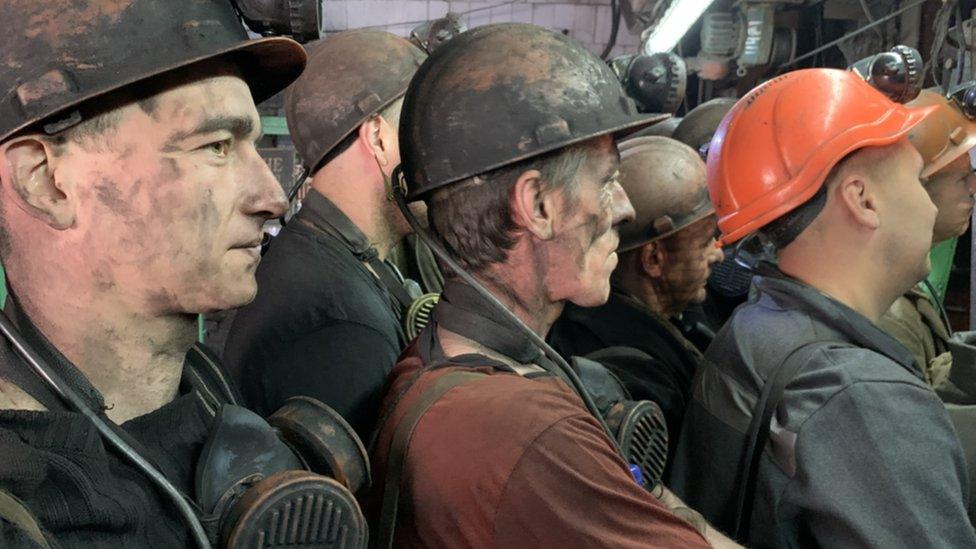

Around her, more than a dozen miners - their faces already smeared with grime - shuffled forwards in the dark towards a rattling iron elevator that stood waiting to take the group 800 metres underground for a six-hour shift.

"We try to be positive. But it's hard on the soul. Depressing. These are terrible times. It's sad at home too - my wife is gone," said Vitaly Vahorder. He's spent half his life working at the Toretsk mine. His family recently joined the exodus heading west to safer locations.

Outside, the occasional boom and crunch of artillery fire echoed across the wheat fields from the front lines 4km to the east and south, where Russian troops are struggling to gain ground against fierce Ukrainian resistance in Donbas.

"People go down the mine knowing they may not come back up. And when you do come back up, anything can happen - the town is constantly being bombed," said Anatoly Sholokhov, deputy head of Toretsk's coal miners' association, as he watched the elevator door slide shut. The 69-year-old miner was born in the town and was once its mayor.

After years of conflict, most of eastern Ukraine's mines have been forced to close

The coal mines, their steep-sided slag heaps dotting the horizon like dark pyramids, have been a defining feature of eastern Ukraine for well over a century. They provided the Russian Empire, and then the Soviet Union, with much of its raw energy. But the collapse of the USSR in 1991, the past eight years of separatist conflict with pro-Russian militias, and the Kremlin's new offensive have combined to force most of the mines to close.

One of many concerns today is that the latest mine closures are happening abruptly, and without proper safety measures, causing old shafts to flood with highly toxic water that threatens to poison local rivers.

"The danger comes when you stop several mines at once," said Anatoly. "You can't control where the ground water goes. It would be a disaster if it comes to the surface. This whole area would become uninhabitable. So, an ecological crisis looms over our town. May God prevent these mines from stopping. If the work stops and water begins to flood the mines, it could cause a catastrophe,"

Only two mines are still working here in Toretsk - formerly called Dzerzhynsk in honour of the founder of the Communist secret police.

The front lines are just four miles from the mine

Driving in from the west, past Ukrainian army checkpoints and roadblocks and into the near-empty town with its Soviet-era architecture and monuments, is like stepping back into the past. A Soviet red star still clings to the top of one of the oldest towers at the Toretsk mine, which first began producing coal in the 1930s, and was badly damaged during World War Two. The mine appears to have experienced few improvements, or even licks of paint, since it was refurbished in 1955.

One sunny morning last week, staff showed visitors around the site. Giant pieces of rusting machinery sat beside doodle-like swirls of rail track, where a lone female worker was busy pushing mine carts into a wooden shed by hand. Two giant slag heaps behind the mine were partially covered with trees and undergrowth. A huge tree grew through one ancient winding wheel. Overhead, floorboards creaked ominously as staff walked along a footbridge from the shaft back to the communal shower block - currently without water, like the rest of the town, due to blockages on a nearby canal which locals blamed on the war.

Only a third of the mine's staff remain since the Russian offensive began

"There's no water anywhere in this town. You go to the toilet - but how do you flush? When it rains, everyone in our apartment block goes out to collect rainwater," said Vitaly.

Only a third of the mine's staff have stayed on in the town since the Russian offensive began earlier this year - some out of loyalty to the mine itself, but mostly for financial reasons.

"I've been working here for twenty years. I went straight to the mines after school. We don't have any other professions here. No factories. We earn 8,000 to 10,000 hryvnias a month (£220 - £275, $275 - $343) and with the current prices that's nothing, tiny, no better than a student's stipend," said Yuri Podlutsky.

As a group, the miners appeared reluctant to pass judgement on the war or President Putin directly. Many of them are Russian-speaking and appeared keen to avoid territory that could cause frictions within a tight-knit community. But several men acknowledged a strong nostalgia for the Soviet era and the times when Ukrainians and Russians worked side by side in the mines.

"Whether you want Putin or not, we still need to live and work. There are a lot of 'Soviets' here," said Vitaly. "I consider myself simply a local. Some of us speak Russian as our first language. But we all share the same sky."

War in Ukraine: More coverage

ON THE GROUND: One man's anti-war protest in a tiny Russian town

READ MORE: Full coverage of the crisis, external

Related topics

- Published20 May 2022

- Published26 May 2022