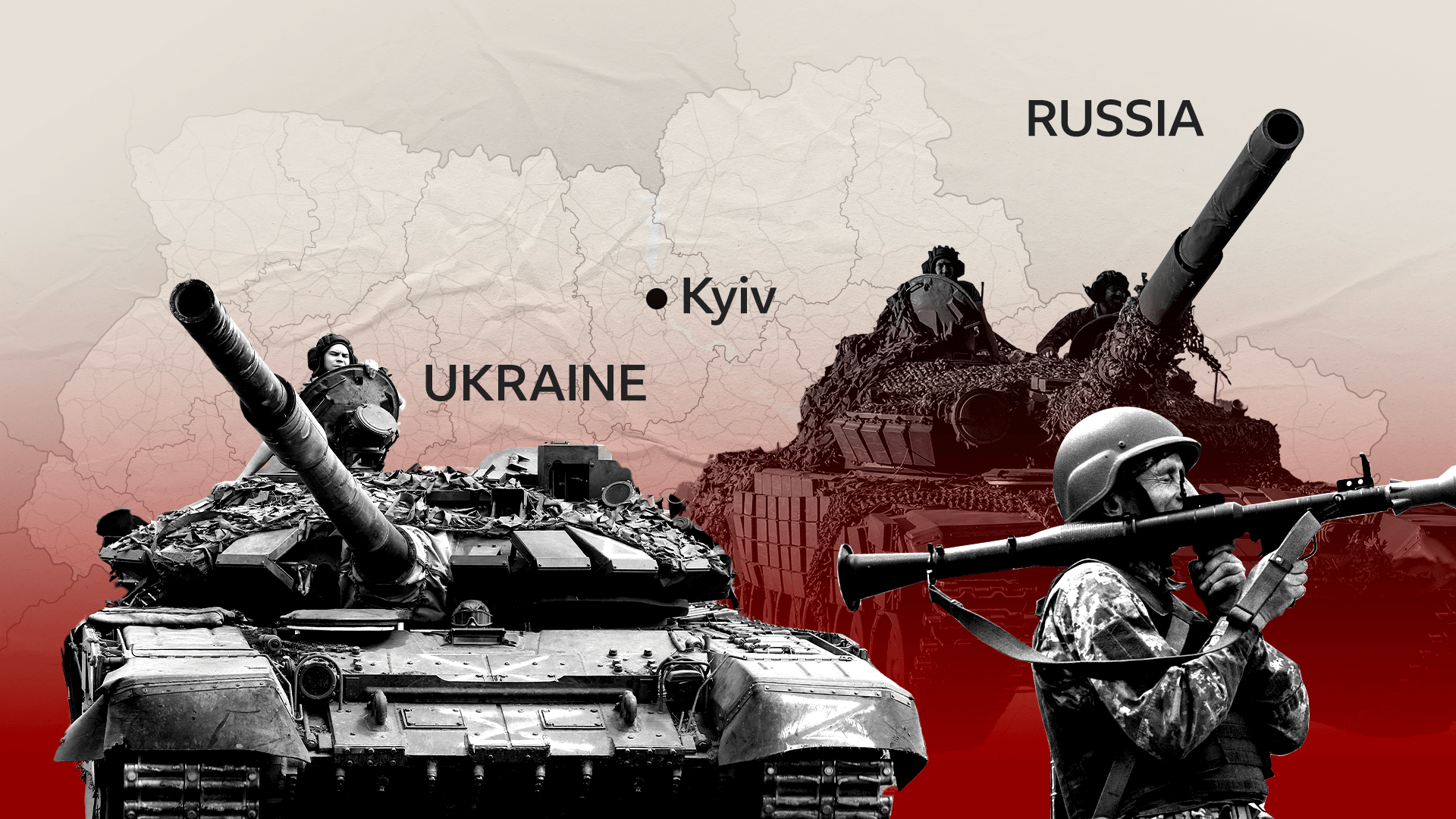

Lysychansk: Russia erasing history in Ukraine's 'dead city'

- Published

Children comfort each other while waiting for evacuation from the region

"Max speed!" The instruction comes via walkie-talkie from the armoured police car in front, as we hurtle past the burnt-out carcass of a Ukrainian military truck. There's a high risk of Russian attack on this stretch of road, but it's the safest route left into the beleaguered city of Lysychansk.

War's dark horizon is ahead of us - black smoke billows from the latest Russian strike. The eastern city - once home to around 100,000 people - is under sustained attack. Ukraine's President, Volodymyr Zelensky, has already pronounced it "dead", along with neighbouring Severodonetsk.

During our visit the thud of incoming artillery is met by the whoosh of outgoing grad rockets. "It's a duel," says the regional police chief, Oleh Hryhorov, succinctly. If so, it's one Ukraine looks set to lose. And soon.

As the Russians close in, some are still trying to get out using evacuations organised by the police. About half a dozen civilians are rushing to board an armoured truck, among them a young boy in a blue peaked cap. At the sound of another shell, they scatter and duck for cover. We learn later that a woman was killed nearby. She dared to leave her apartment but made it only as far as the front garden.

Life and death are separated here by slim margins.

We meet an elderly woman wandering in the street - clearly shell shocked - clutching a small religious icon. She was near the scene of a strike that set a house alight.

"In Lysychansk, if you are alive, it is a good day," says the police chief, who oversees the Luhansk region that covers half the Donbas and is now almost entirely in Russian hands.

He speaks in a low voice laced with tension and exhaustion, and acknowledges that fear comes with the territory here. "Anyone who says they are not afraid is lying," he says. "Nobody wants to die. But our brave Ukrainian policemen carry on doing their jobs." He takes bitter-sweet pride in the fact that they have helped to evacuate 37,000 people from the region.

As we speak, a Russian shell whistles over our heads forcing us to duck for cover. Within minutes it's followed by another.

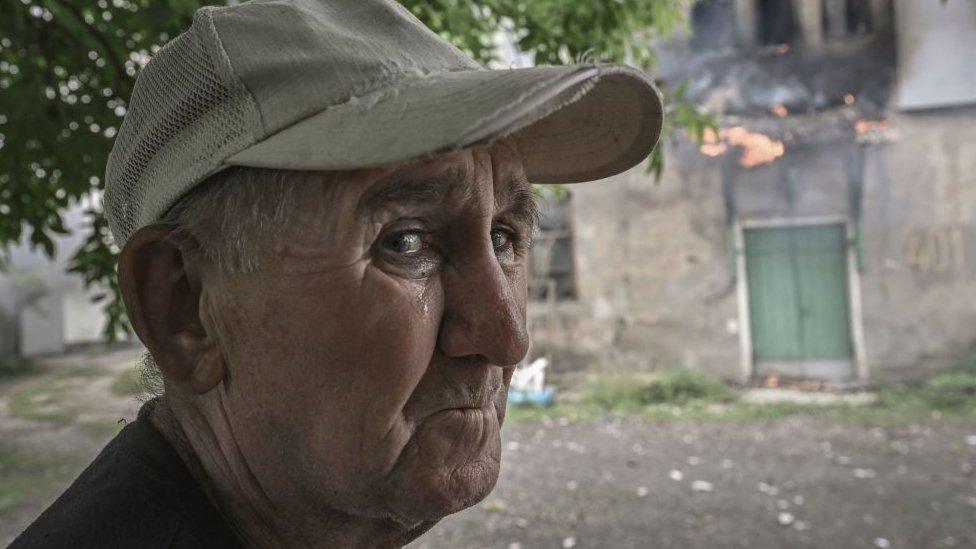

Volodymyr says they have been living without water, gas and electricity

Soon a cluster of civilians gather, waiting for the next evacuation run. The sound of more incoming fire sends some rushing for shelter. But Volodymyr remains sitting. The grey-haired 67-year-old may be too ill to move. He tells me, with a sigh, that he needs to get to hospital.

"Life here was calm before. It was normal. Then the war broke everything apart. There has been no water, no electricity, no gas. I'm in despair," he says quietly. "In despair."

Those who remain make brief escapes from their basements to cook outdoors. We meet Yelena and her relatives sitting on a bench near a makeshift oven - a macabre barbecue imposed by war.

Yelena and her relatives have remained in the city

She's ashen faced, but still clinging to her home of more than 50 years.

"We have lived here all our lives," she said. "We are a big family with sisters and brothers, children, and grandchildren. All of them are here. We haven't thought about leaving." As we speak there are more thuds in the distance.

"We are worried about ourselves, our family, our pets. We are worried about everything. But we are hoping that everything will be okay."

There's little chance of that. This is now an artillery war, and Ukraine doesn't have enough big guns. The mathematics are stark. Officials say they have one artillery piece for every 10-15 Russia has. Added to that, Ukraine is running out of ammunition.

So Lysychansk is being pounded, and the fabric of the city is being destroyed. The once imposing Palace of Culture is now a charred shell, its graceful columns blackened and broken. Russia isn't just bombing buildings here, it's erasing history. The tactic is deliberate - shell, flatten, crush, and leave nothing but scorched earth.

The columns of the Palace of Culture are now charred and broken

From Lysychansk it's not hard to see Russia's vision of the future.

It's just down the road in the twin city of Severodonetsk. We could see fires burning there, on the opposite bank of the Siversky Donets river.

There are a few remaining pockets of Ukrainian resistance in Severodonetsk, but the city could fall within days. If so, that will be a key victory, allowing Russian President Vladimir Putin's forces to move on to the rest of the Donbas. He and his proxies already control most of it.

Ukraine is facing an enemy that has learned lessons and is imposing heavy losses. The government says between 100 and 200 troops are being killed in battle every day. And what of the handful of advanced long range rocket systems promised by Britain and the United States? They may be too little too late.

"If the weapons had arrived sooner, we would have stopped the Russians much earlier," says Serhiy Haidai, the governor of Luhansk.

"Moreover, we would have been able to launch a counterattack." The destruction of Severodonetsk is painfully personal for him - it's his hometown.

We catch up with him for an interview when he is on the move. Like the police chief, he is a worried man, in a hurry, as the last of his region is being devoured.

A damaged building can be seen in Lysychansk as black smoke rises from the nearby city of Severodonetsk

The governor warns that the risk does not stop at the borders of Ukraine. "If Putin is not stopped, he will move on," he says. "He will advance to the Baltic countries, to Europe. He will fight, he is a completely deluded man. And he can be stopped only by force."

Governor Haidai says he still believes in victory. That view is echoed in Kyiv. But here on the ground in the Donbas region it looks like Ukraine is fighting a losing battle, and this will be a summer of defeat.

Soon Lysychansk and Severodonetsk may be among the new ghost cities of Ukraine.

And as the months go by and Russia grinds forward, there may be another danger - that Western attention, unity and support will begin to ebb away.

War in Ukraine: More coverage

Related topics

- Published6 June 2022

- Published12 June 2022