Ukraine war: G7 leaders pledge action on Russia - do we believe them?

- Published

Ukraine's President Volodymyr Zelensky addressed the G7 summit via video-link, calling for more weapons for Ukraine

"Show them our pecs!"

Boris Johnson's quip calling on fellow leaders of the world's seven richest countries - the G7 - plus the European Union, to show some serious muscle has become the stand-out moment of their meeting in a luxury German hotel.

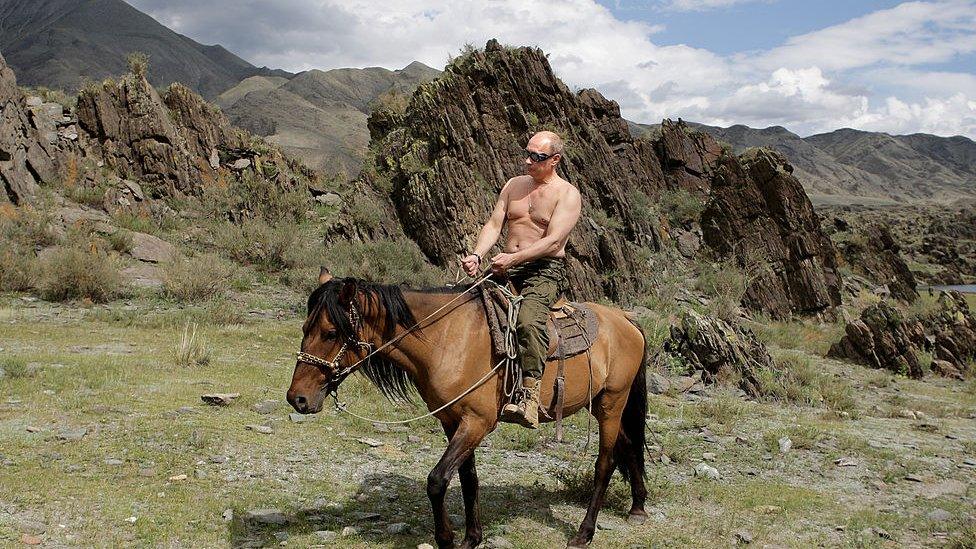

The UK prime minister was clearly mocking Russia's Vladimir Putin, who is famously fond of bare-back horse riding for the cameras.

But is this a time to joke?

Canada's prime minister and the EU Commission Chief whole-heartedly joined in the ha-ha moment.

The Kremlin, meanwhile, is stepping up its deadly onslaught in Ukraine. A world food crisis is spreading as a result of Russia's blockade on Ukrainian grain, which is desperately needed in Africa and the Middle East. Food and fuel prices are spiralling across Europe too.

European economies and families are increasingly hard-hit.

But Mr Johnson is also right. Now is the time that Western leaders and their allies must make a serious impact if they are to counter Russian aggression and its fair-weather ally China in any meaningful way.

The increasingly anxious and beleaguered voters of these G7 countries and their allies may find the joking around and posing for awkward photographs easier to accept - even welcome - if they result in concrete action.

Watch: 'Show them our pecs' - G7 leaders mock Putin

We're now mid-way through a week of high-level meetings.

EU leaders gathered in Brussels before the weekend and the G7 summit is in full swing in the Bavarian mountains, while other world leaders are already arriving in Madrid for what's being billed as the "most crucial" meeting of the Nato defence alliance in years.

The overwhelming focus is Russia, Ukraine, China and the "what next?"

In the past, these annual meetings have been dismissed as talking shops, filled with vague-sounding promises, that too often result in too little. Think of the Build Back Better World initiative, announced at last year's G7, for example.

Now in Bavaria the G7 has announced a $600bn (£490bn) infrastructure plan, specifically aimed at emerging economies to counter China's spreading global influence.

Leaders also pledged new sanctions on Moscow to limit its ability to import technologies for its arms industry. This, in addition a possible price cap on Russian oil exports, is designed to hit the Kremlin's war chest hard. But it's an initiative that can only work if enough countries, and the world's biggest economies most of all, are on board.

Ukraine's President Zelensky certainly aims to put leaders on the spot en masse this week. His message: Deliver more powerful weapons to us faster "if you are true partners, not merely bystanders."

To be credible, this week's Nato meeting will require Western powers and allies, (Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand have been invited as observers) to nail down a common position on Russia.

And that's going to be tough.

Washington is anxious that the West maintains a united front. Arriving in Bavaria, President Biden insisted the G7 countries and Nato must "stay together" in the face of Russia's invasion.

He knows Vladimir Putin is watching for weakness and keen to exploit it.

The need for Western unity

Moscow can see the domestic struggles facing these leaders.

Joe Biden and Boris Johnson have members of their own party openly questioning their leadership; France's Emmanuel Macron just faced a bruising parliamentary election; Italy's Mario Draghi has seen his coalition partner, 5 Star, split down the middle; and Germany's Olaf Scholz's Social Democrat Party is divided over just how far and how long to keep Russia at arm's length.

The Kremlin will also relish Hungary's slowing of EU sanctions against Russia, and Turkey delaying the Nato membership bids of Finland and Sweden.

Western splits over how to handle Russia are fundamental.

All leaders say they support Ukraine. The EU threw convention to the wind on Thursday, offering Ukraine candidacy for EU membership - though it may take several years to make it into the bloc, if at all.

Strong statements of solidarity and promises of funding and military support for Ukraine will be heard across all this week's meetings.

But Western leaders are divided as to how far they should push Russia.

Vladimir Putin, pictured in 2009, has often posed shirtless for photos - something the UK PM made fun of during the G7 summit

"Into a corner and beyond", is probably how you can sum up the UK view, championed by Poland, the Baltic countries and much of central Europe too.

But Germany, Italy and France are more hesitant. They haven't quite let go of the idea, if not the hope, that Russia can still be a partner for dialogue further down the line. Whether in terms of business or wider security diplomacy, as Europe scrambles to re-design its security architecture which has been decimated by Russia's invasion and threats of nuclear strikes.

This does not mean that Germany, Italy or France are pushing Ukraine towards a ceasefire at any cost. Though the suspicion was there.

The G7 leaders communique on Ukraine pointedly includes the line: "It is up to Ukraine to decide on a future peace settlement, free from external pressure or influence."

It had taken a long-awaited trip to Kyiv recently by Chancellor Scholz, Mr Macron and Mr Draghi to clear the air.

Germany has now made its first heavy weaponry delivery to Ukraine and Chancellor Scholz has called for a modern Marshall Plan - a post-World War Two US aid program - to re-build the country.

We can't, of course, forget his historical promise to massively modernise Germany's armed forces so it can play a more effective role in common European security too.

But no-one could accuse powerhouse Berlin of leading from the front here.

In fact one thing has remained resolutely unchanged in security terms since Russia's invasion of Ukraine: Europe has failed to stand on its own continental feet and still has a deep dependence on the US.

War in Ukraine: More coverage

KLITSCHKO: 'Russians dying for Putin’s ambitions'

BABUSHKA Z: The real identity of Russia's propaganda icon

READ MORE: Full coverage of the crisis, external

- Published26 June 2022

- Published27 June 2022