Unique terror trial that changed France

- Published

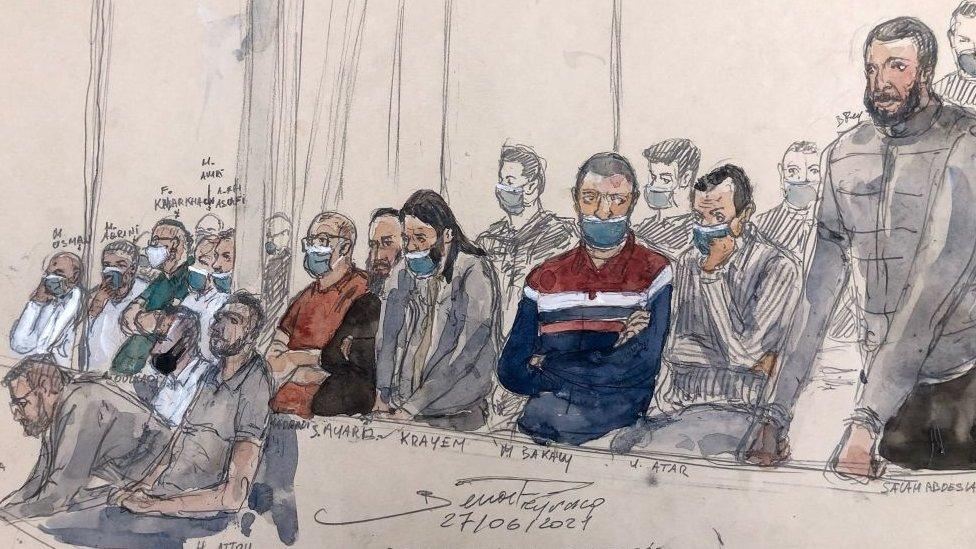

Salah Abdeslam (bottom R) was the first person to be given a full-life sentence without killing anyone

It was a trial to match the scale of the crime.

More than 400 survivors and relatives of the dead came forward to bear witness to France's worst peace-time attack.

Fourteen defendants were questioned in a courtroom specially built for their trial, about the terrorist plot that claimed 130 lives on one night in November 2015.

Nine months of hearings were interspersed with breaks, each week, to allow emotions to settle.

"There has never been a trial like this in our history," France's counter-terrorism prosecutor, Jean-François Ricard, said the morning after the verdict.

"It went beyond law," said Laure Khalil, who represented more than 100 victims and their families. "I would spend hours on the phone listening to one client telling me how she felt the day before. As lawyers, I'm not sure we're prepared for this."

"This is the first time I've cried in court during a testimony," Julia Courvoisier, another lawyer for victims, told us. "This story belongs to all French people: as lawyers, we may have had less distance from the facts than in other cases."

Aside from its scale, this trial was unique in the role it played for France. The purpose-built courtroom, with cameras filming proceedings for the national record, told of a process that went beyond simple justice.

That much was clear in the space and focus given to the victims. In some ways, this trial belonged to them more than to the defendants.

It was always important that this process give survivors a chance to tell their story for the public record. It was something many of them said they valued more than anything else.

The individual judicial processes of 20 men could sometimes feel like a sideshow, set against the hundreds of searing experiences the victims shared, and against the backdrop of national trauma this event caused France.

"We waited four and a half months before the defendants could have their say," said Julia Courvoisier. "In three-day trials, you can wait a day to hear the accused. But with the number of civil parties who came to testify [here], the accused did not have the floor until January. Maybe in future, we'll have to try to find a different format."

French law allows civil parties the right to testify in criminal trials, and for their lawyers to ask questions of the accused. But the sheer number of civil parties in this case - most of them victims or their representatives - dwarfed the number of defendants.

"There was a kind of disproportion," said Laure Khalil, the lawyer representing more than 100 of them. "It raises questions: when there is so much suffering, what should we do with it? Should the judge take it into account when deciding the guilt of the accused?"

Bataclan survivor Arthur Dénouveaux said the road to justice for the victims had taken more than six years

She says the 13 November trial could lead to civil parties having a different kind of status in French courtrooms, and being given more consideration in future.

"I don't know if that would be a good thing," she said. "I don't know if we will find the answers, but this type of trial raises questions."

Many of the survivors said the verdicts themselves were less important to them than piecing together the story of the attacks, and finding themselves in that story.

"For me, it was very healing," said David Fritz Goeppinger, one of the last hostages to leave the Bataclan concert hall that night. Sharing his testimony with the court was different to sharing it with friends, or journalists, or anyone else, he said.

"Something shifted, because it was as if my story was not mine anymore: justice will use it to deliver a sentence. We need to let go, in order to exist."

'We still have our nightmares": Survivors and family members of victims react to Paris attack verdict

"I didn't have any particular expectation or requests concerning the verdict," said Stéphane Sarrade, whose son Hugo was among the 90 people killed in the Bataclan attack. "What was important for me was that [the defendants] had to face their responsibility for this tragedy."

But the verdicts in this trial also shifted the ground beneath French justice.

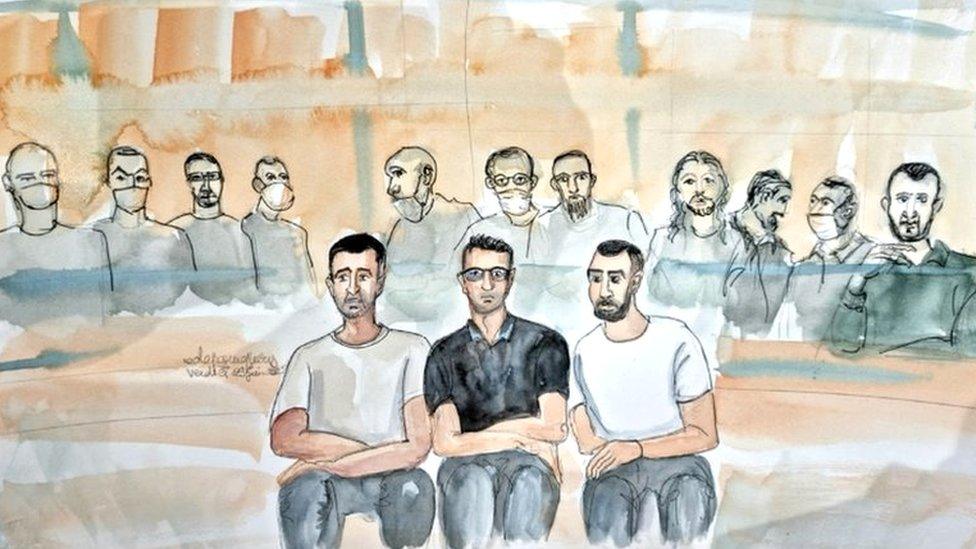

Salah Abdeslam, the key defendant and the only surviving member of the terrorist cell that carried out the attacks, was given a full-life sentence.

It's the heaviest penalty France can hand down. But Abdeslam is the first person to receive the sentence without being convicted of killing anyone directly himself. The court judged the multiple attacks across Paris to be a "single crime scene" in which Abdeslam was a co-conspirator.

Legally, his sentence rests on the attempted murder of police officers at the Stade de France by three other attackers, driven there by him.

Where Paris attacks took place

Only four other defendants in French legal history have received this sentence, all of them for multiple killings or child murders.

One of Abdeslam's lawyers, Olivia Ronen, said his sentence was "what we would have asked for the real authors of the Bataclan attack, but it's clear that we don't have them and that someone has to be punished".

"It's very important; it's a precedent," legal expert Jean-Pierre Mignard told us. "But obviously the events must be extremely serious and the criminal participation must be identical in seriousness to his case."

The sheer length of the trial also allowed time for the audience to witness an evolution in the defendants.

Several of the accused appeared very emotional as they paid tribute to the victims in their closing statements.

Salah Abdeslam, who defiantly introduced himself as a "soldier with the Islamic State [group]" during this opening statement to court last September, ended his testimony earlier this week with a tearful apology to victims and a plea to the court that he was "not a killer".

Being surrounded by people during the trial, after six years in isolation, had changed him, he said.

Abdeslam's lawyer, Olivia Ronen, said his full-life sentence did not fit his crime

Perhaps more than anything, though, this trial is unique in the role it played for the France outside the courtroom.

Its importance for the nation's sense of security could be measured, day after day, by the long queues of journalists standing at the back entrance of the Palais de Justice in Paris.

This was the French state publicly imposing order on the chaos and insecurity of 13 November by creating an official narrative of events and, as the daily newspaper Le Monde put it, applying "ordinary justice to extraordinary facts".

A response, the paper says, "worthy of a vibrant and resilient democracy… In contrast to the American fiasco after 11 September 2001, marked by the use of secret prisons, interrogation methods that verged on torture, and dead-end military courts".

"I'm pleased both as a lawyer and a Frenchwoman that France carried out a trial like that," Julia Courvoisier said. "There were no security concerns, the rights of the defence were respected, everyone was able to speak. I think it's beautiful that we responded with our legal system - no more, no less."

This immense judicial operation was the second of three high-profile terrorism trials for France. The trial into the Charlie Hebdo attacks ended in 2020, and hearings for the 2016 truck attack in Nice will begin this September.

It's likely there will again be a focus on victims and a lot of media interest in the Nice process, but few believe it will match the impact of the November attacks trial.

"It was a staggering experience," said lawyer Laure Khalil as the marathon process in Paris wound up this week. "I ended up thinking that all other trials would look ordinary compared to this."

- Published30 June 2022