Ukraine war: Why I never gave up trying to find my children

- Published

The reunion was incredibly emotional

When Russia invaded Ukraine, the outbreak of war meant a family of foster parents faced indefinite separation from six of their adopted children. Hearing about forced adoptions to Russia, they feared they would never be reunited.

As she was alerted to the invasion, Olga Lopatkina's first thoughts were for her six adopted children who were visiting the seaside, 100km (62 miles) away from home.

They were in a municipal holiday home near the sea, where they had been sent for fresh air and general wellbeing.

It quickly became too dangerous to collect them, with heavy shelling in towns along the route from their home to where the children were.

Olga faced an impossible choice - sending her husband Denis on a perilous drive to rescue them or leaving the children in Mariupol, where they had gone for their break. At that time it still seemed relatively secure.

"We started panicking and didn't know what was the best thing to do," she says.

The complete destruction of Mariupol would later become synonymous with Russia's carpet shelling of cities into submission.

The brutal reality of war hit home after just two days, when Olga encountered refugees from the east. She was shocked to see how quickly normal life had deteriorated.

Like many people in Ukraine, Olga assumed the war would stop within days or weeks, and hoped the children would be evacuated to a safe area by the Ukrainian authorities.

It soon became clear that the conflict was intensifying and the children were extremely vulnerable. If they were not killed by an explosion, she worried for their future under Russian control.

Reports started emerging of civilians, both adults and children being transferred to Russia. Moscow called these transfers "evacuations," while Ukraine branded them forceful deportations, reminiscent of practices under Stalin in the 1940s.

The couple began adopting in 2016. By February this year, when the war started, they had seven adopted children aged six to 17. This was in addition to their two biological children.

"We are crazy people but we like it. Children give us emotions which we wouldn't otherwise have - life was empty before them," she says.

Olga worked as a music teacher in Ukraine, now she is a seamstress

Olga worked as a children's music teacher and Denis a miner. Their life was happy and full.

But at the beginning of March, the family was fragmented and scared.

Electricity at the sanatorium, which was being shelled, was cut off and children could no longer charge their phones, meaning Olga could not speak to them.

At their own home in the eastern town of Vuhledar, the Lopatkins too sheltered in their basement as the war moved closer. "We were bombed and bombed all around, it's scary," Olga says.

They decided to drive to Zaporizhzhia, where they knew some people from Mariupol were being evacuated, hoping the Ukrainian authorities would arrange for the children to be taken there too.

But the city was not safe. With no sign of the children, the family decided to move further west to Lviv.

There, a new problem arose, with concerns Denis would be drafted into the army. Reluctantly, they decided to flee Ukraine.

Less than two weeks after the war started, Olga, Denis and their remaining three children were refugees themselves - but Olga says she never gave up hope of getting the children back.

The family were in Germany, deciding where to relocate to, when they next heard from the children.

They had been transported to a part of Donetsk region controlled by pro-Russian separatists, where they were placed into a TB hospital. This was because they had arrived from a sanatorium used to recuperate respiratory patients.

Social services told the children they had been abandoned.

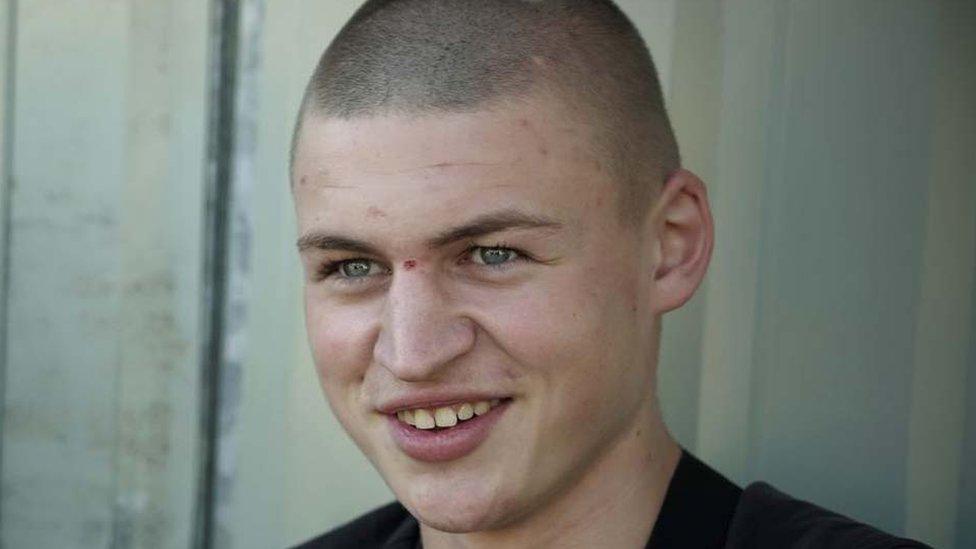

Timofey and Olga repaired their relationship

The eldest child, 17-year-old Timofey, was able to charge his phone and texted Olga. He said he had been offered chances to leave on his own but rejected them to care for his siblings and was angry she had left Ukraine.

"I understood they couldn't come and get us from Mariupol, but that they had gone abroad really triggered me," he says.

Feeling helpless, Olga continued to post on social media asking for help and information about her children, but mostly received abuse. Many accused her of not trying hard enough to rescue the children and even more criticised her for leaving Ukraine. Accusations and suggestions that she could abandon her children hurt her deeply.

She spoke to the international media to reiterate her message.

"I tried every way to publicise our situation, hoping that someone will hear something and be able to help," she says.

Meanwhile, the couple were deciding where to settle in Europe. They picked the small town of Loue in north-western France where they set up new lives, with jobs and a house subsidised by the Red Cross, large enough for all the children.

The town's mayor had invited ten Ukrainian refugee families to settle, with special efforts made to accommodate foster families.

By early April, Olga and Timofey established a routine of speaking on the phone most evenings, which helped to repair the relationship.

It was a question of waiting and hoping the Donetsk social services would agree to release the children, which they did.

But it was not that simple. They would only give them to their legal guardian - Olga. And she would have to return to the place she had just fled.

"I was a refugee running away from the Russian Federation and now I would go into the Russian Federation?" she scoffs.

For a while things seemed to be at an impasse. The Donetsk social services were demanding Olga send the children's birth certificates to prove their identity, but she worried this would lead to them being put up for adoption.

This fear had a real basis. Russian TV regularly broadcasts upbeat reports on the "evacuation" of civilians from the "liberated" regions of Ukraine.

Tatyana is an experienced volunteer who worked with orphaned children for many years

Kyiv says it is forceful deportation and in the case of orphaned children is tantamount to kidnapping.

In May, President Putin issued a decree "simplifying" the issue of Russian documents to children from Ukraine. Ukraine's Foreign Ministry protested, labelling it a violation of the Geneva convention of human rights.

Earlier this month, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky said up to two million Ukrainians had been forcefully deported to Russia, hundreds of thousands of them children.

Then there was a glimmer of hope. In June, Olga received a phone call. There was someone in Donetsk who could bring her children to western Europe.

Tatyana, an experienced volunteer in Donetsk who had worked with orphaned children and vulnerable mothers for many years, had a working relationship with the authorities and was willing to help.

Olga and Denis gave the children's documents to Tatyana along with a release form, making her their temporary legal guardian. They had to take a leap of faith, but Olga says it felt right.

The process still wasn't simple, they only knew at the last moment that the paperwork had gone through and they would soon be back together.

Tatyana travelled with the children to Russia, then to Latvia and Germany. Each border crossing was nerve-wracking.

"They all have different surnames, the original of the release form was in French, I had to explain our situation over and over to countless border guards," says Tatyana.

She took the children as far as Berlin where she handed them over to Denis who drove them to their new home in Loue.

Watch the moment Olga was reunited with her children in France

The family's reunion after four months of uncertainty and anxiety was exceptionally emotional.

Tears were mixed with laughter as first Denis and later Olga crushed their kids in hugs, still not believing they were seeing them for real.

Olga kept hugging the children, saying: "Let me look at you, let me just look at you! You grew so much, I haven't seen you in such a long time!"

Timofey held back from showing too many emotions: "I am very glad it all worked out but I am also older so I don't show how happy I am. I am glad we are all together again and I kept my word and brought the kids to the parents."

Olga is forever grateful to the woman she never met and describes as "our heroine".

In the family's immediate plans is a well-deserved holiday. Olga is hoping to go to Portugal.

"I've never seen the ocean," she says. "Of course, we are all going together. I'm not letting them out of my sight again," she laughs.

Additional reporting by Anastasia Lotareva and Alexey Gusev. Photos by Vladimir Pirozhkov.