Inishowen, Donegal: Ireland's poitin republic

- Published

The name poitin, or poteen, is derived from the ancient gaelic words for "small pot" and "small drink"

County Donegal is best known for its spectacular countryside, unspoiled beaches and relaxed pace of life.

However, in the 19th Century the county, in the north-west corner of Ireland, was at the centre of an illegal trade in what is sometimes called Irish moonshine.

Distilled from barley, poitin is a strong, clear alcoholic spirit, first outlawed in the 17th Century.

While it was ever-present across Ireland since first being produced hundreds of years earlier, poitin production reached its peak in the early 19th Century, with thousands of gallons being made annually after taxes on whiskey were increased.

The Inishowen Peninsula in northern Donegal was part of which would be labelled the "poitin republic", from where the illegal spirit would be smuggled to Belfast, Dublin and even Scotland.

"People decided: 'Why pay the tax when we can do this ourselves?'," says author and historian Seán Beattie of the Donegal Historical Society.

"Inishowen was ideal for it - it was hard to get to; there were very few police barracks.

"So it became a thriving, illegal place for making poitin.

"There are records of shiploads being shipped off from the harbour in Culdaff to Scotland."

'Reputation for quality'

So prevalent did it become that the commissioner for customs and excise in Dublin called the area around Urris the "poitin republic".

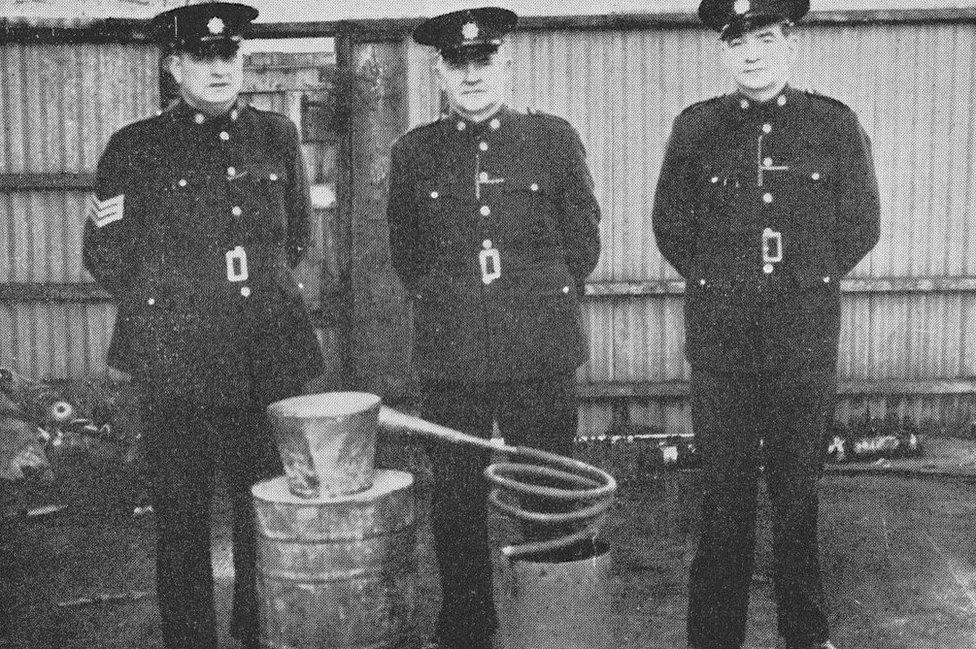

Remote rural areas were considered perfect for the drink's production

"A huge trade developed, a massive trade," says Mr Beattie.

"Places like Moville and Culdaff and Clonmany all had piers and barley was imported from Scotland in huge quantities.

"Then the poitin was exported to Scotland and sent on to Dublin, Belfast by boat and other counties in Ulster.

"They invented a brand of poitin called Inishowen, which had a reputation for quality so was very marketable."

So popular was the illegal whiskey that a formerly-successful legal distillery based in the area - Leathem's - went out of business.

Mr Beattie says the trade was comparable with that of drugs such as cocaine nowadays.

"Why are drugs criminals successful? Because there's a demand for it and there was a huge demand for poitin," he says.

"People took it when they had the opportunity of getting it cheaper and paying no tax on it."

'Developed a skill'

While consumers were drawn by the price and strength of poitin, the money that could be made from it attracted producers.

"It was income for a family," says Mr Beattie.

"Most families were very, very large, living on a patch of ground, so if you could get into the poitin business and grow a bit of barley or leased land and rent it, it could increase your income.

"It was a very simple process - the big problem making it was the smoke, you could see the smoke going up in the hills, that's why remote areas were so successful.

"It was mostly poor rural areas of Donegal, they could grow barley there and also import it cheaply and as time went on they developed a skill and became good at it."

While it never again reached the levels of the early 19th Century, poitin production continued in the 20th Century as these Garda (Irish police) officers with a confiscated still show

However, success for the producers meant lost income for the government and a response was inevitable.

"When the government discovered they were losing vast amounts of money they sent in the army and that then escalated the whole situation and you had a cutter on the [River] Foyle to block it and try to stop it," says Mr Beattie.

"From 1814 to 1818 the government clamped down really hard and invented something called townland fining.

"What they did was if a piece of equipment like a still or even a bit of a still was found in a townland, they couldn't honestly say who was the distiller, but what they did was they fined everybody in the townland.

"Then of course people couldn't pay their fines so the next stage was the army would move in and the police and they'd round up livestock and put them into pounds and that in turn generated huge poverty and hardship for people.

"The fines were huge - in the parish of Culdaff alone in 1815, 248 people were fined a total of £6,000 - a lot of money and they couldn't afford to pay it, leading to confiscations and the landlords didn't get paid as well so there'd be huge social problems all round."

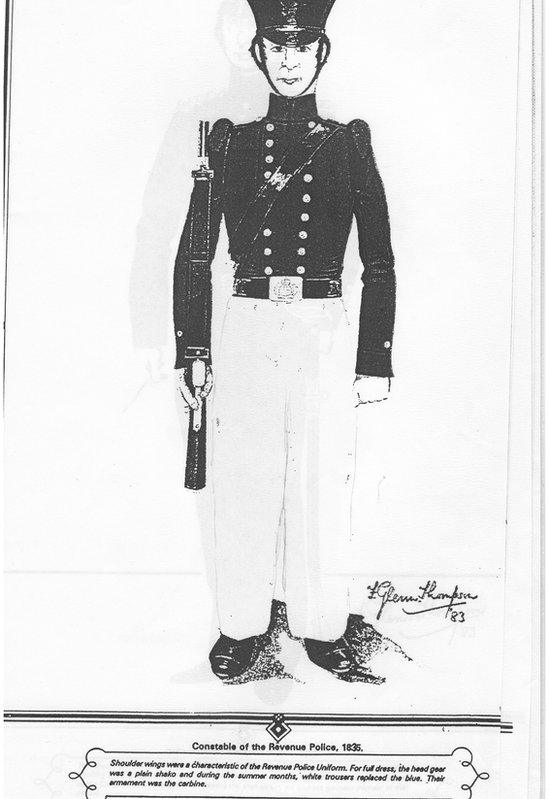

An illustration of a revenue police officer in the early 1800s - the government's harsh clampdown drew criticism from catholic and Protestant churchmen

The townland fines were criticised by church leaders, both Catholic and Protestant.

Pamphlets were issued by churches criticising the revenue officers, who in turn issued pamphlets criticising the churches and accusing them of supporting poitin trade.

"Landlords were also accused of encouraging poitin making, because people who made poitin made money and they could pay their rents," says Mr Beattie.

'Daddy of all whiskey'

There were also, of course, health implications of drinking a spirit with an alcohol content that could be anything from 40 to 90%, with some people recorded as going mad from drinking too much poitin.

While the government clampdown had an effect in suppressing the trade to an extent, it kept going on for most of the 19th Century, interrupted by the famine.

In the early 1890s it flared up again, sparking the Catholic Pioneer movement and temperance initiatives from Protestant churches.

Poitin stills continued to be seized across Ireland throughout the 20th Century.

However, in 1997 it was legalised and in 2008 was awarded an EU geographical indication, meaning it can only be produced on the island of Ireland.

It has enjoyed something of a renaissance as a result and while there are those who argue legal poitin is something of a contradiction in terms, others say the spirt is the "daddy of all whiskey".

Whatever the case, in the 19th Century at least, the epicentre of the trade was in the rugged north of Donegal.

Related topics

- Published20 September 2020