Ukraine nuclear plant: How risky is stand-off over Zaporizhzhia?

- Published

Ukrainian officials previously staged an exercise in case of possible nuclear disaster

UN nuclear inspectors have made an appeal for fighting to stop at Europe's biggest nuclear power plant - close to the front line in Ukraine - to help prevent a nuclear accident.

Rafael Grossi, the head of the International Atomic Energy Agency, has warned of a very real risk of nuclear disaster. He has led a team to the plant where Ukrainian staff have worked in highly challenging conditions for months.

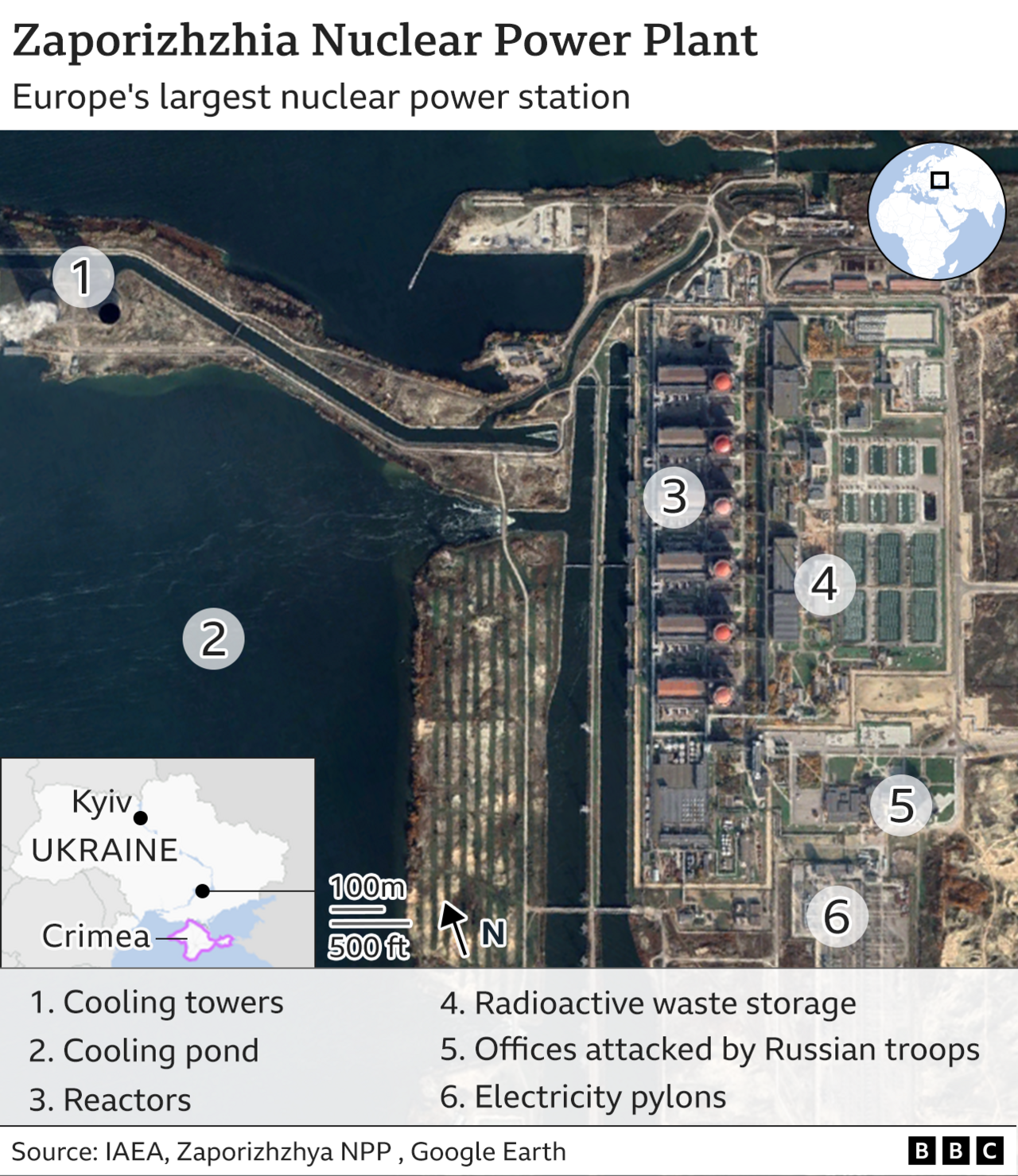

Russia seized the Zaporizhzhia plant on the left bank of the River Dnipro at the start of its war and the two sides have since accused each other of repeatedly shelling it.

When the plant was temporarily cut off from Ukraine's power grid for the first time in its history in late August, Ukraine's president said the world had narrowly avoided a radiation accident. Russian officials have even produced a map of how a radioactive cloud might spread to neighbouring countries.

What, then, is the risk to this nuclear plant which houses six reactors - and is Europe facing a Fukushima-type meltdown?

Much of the anxiety has been about the plant coming under fire from artillery shells or rockets. Ukraine has accused Russian forces of using it as a shield from which to fire on nearby cities. Russia denies that is the case, but satellite photos have shown their military stationed near some of the buildings.

"Zaporizhzhia was built in the 1980s, which is relatively modern," says Mark Wenman, head of the Centre for Doctoral Training in Nuclear Energy Futures. "It has a solid containment building. It's 1.75m [5.75ft] thick, of heavily reinforced concrete on a seismic bed [to withstand earthquakes]... and it takes a hell of a lot to breach that."

He rejects comparisons with either Chernobyl in 1986 or Fukushima in 2011. Chernobyl had serious design flaws, he explains, while at Fukushima the diesel generators were flooded, which he believes would not happen in Ukraine as the generators are inside the containment building.

After 9/11, nuclear plants were tested for potential attacks involving large airliners and found to be largely safe, so damage to a reactor's containment building may not be the biggest hazard.

More worrying is loss of power supply to the nuclear reactors. If that happens and the diesel back-up generators fail, that would lead to a loss of coolant. With no electricity to power the pumps around the hot reactor core, the fuel would start to melt.

The plant was temporarily disconnected from Ukraine's grid on 25 August, when fires twice brought down its last remaining 750 kilovolt power line. The other three were put out of action during the war.

In the event, electricity was sourced to a less powerful line from a coal-fired thermal power station near by and officials said the diesel generators were also used.

However, Ukraine's nuclear agency says the generators do not provide a long-term solution and if that last power line from the national grid is broken then nuclear fuel could begin melting, "resulting in a release of radioactive substances to the environment".

Lt Gen Igor Kirillov of Russia's nuclear protection corps says shelling has already damaged the plant's support systems, so a pump and generator failure could lead to the reactor core overheating and the plant's facilities being destroyed.

"That wouldn't be as serious as Chernobyl, but it could still lead to a release of radioactivity and that depends which way the wind's blowing," says Claire Corkhill, professor of nuclear material degradation at the University of Sheffield.

For her, the risk of something going wrong is genuine - and Russia would be just as much at risk as Central Europe.

But Prof Iztok Tiselj, chair of nuclear engineering at the University of Ljubljana in Slovenia, believes the risk of a major radioactive incident is minimal as only two of the six reactors are now operating.

"From the standpoint of European citizens there's no reason to worry," he says. The other four are in a state of cold shutdown, so the amount of power needed to cool the reactors is smaller.

Mark Wenman is full of praise for the Ukrainian staff at the plant for reducing the number of reactors in operation.

That means that even though the radioactive products continue to be radioactive, the so-called "decay heat" after a shutdown decays exponentially with time. "Provided the diesel generators are in good shape, even if they lost electricity from the grid they should be able to cool the reactor," he says.

Another major safety risk could come from the spent fuel at Zaporizhzhia. Once the fuel is finished the waste is cooled in spent fuel pools and then moved to dry cask storage.

"If these were to be damaged there would be a release of radioactivity but it wouldn't be anywhere near as serious as the loss of coolant," says Prof Corkhill. And Iztok Tiselj believes any release would be so small as to be negligible.

At the heart of this crisis are the plant's original staff, working under Russian occupation and under a great deal of stress. Two workers have told the BBC of the daily risk of being kidnapped.

In August, the UN secretary general called on Russia to pull its troops out and demilitarise the area with a "safe perimeter". Russia has refused, arguing that would make the plant more vulnerable.

Employees have warned of disaster if Russia tries to shut the whole plant down, in order to disconnect the supply from Ukraine and reconnect it instead to Russian-occupied Crimea.

Dr Wenman believes it is the human factor that represents the biggest risk of a nuclear accident, whether because of chronic fatigue or stress: "And that violates all the safety principles."

If something were to go wrong, they would need to be on top form, and one can imagine they are not, says Claire Corkhill.

A letter signed by dozens of employees has called on the international community to stop and think: "We can professionally control nuclear fission," it said, "but we are helpless in the face of people's irresponsibility and madness."

War in Ukraine: More coverage

- Published9 September 2022

- Published4 March 2022