'If I'd stayed in Afghanistan, I'd be dead'

- Published

Rahmat says he wouldn't be in Calais if Afghanistan was safe

A year ago today, Western countries led by the US pulled their troops out of Afghanistan after 20 years, leaving the country in the hands of the Taliban.

Thousands of former government workers and security officers and their families who had worked with international forces suddenly found themselves in fear of their lives. Many fled and still have no place to call home.

For their safety, all contributors names have been changed

"It's the first time I've ever seen the sea," says Rahmat.

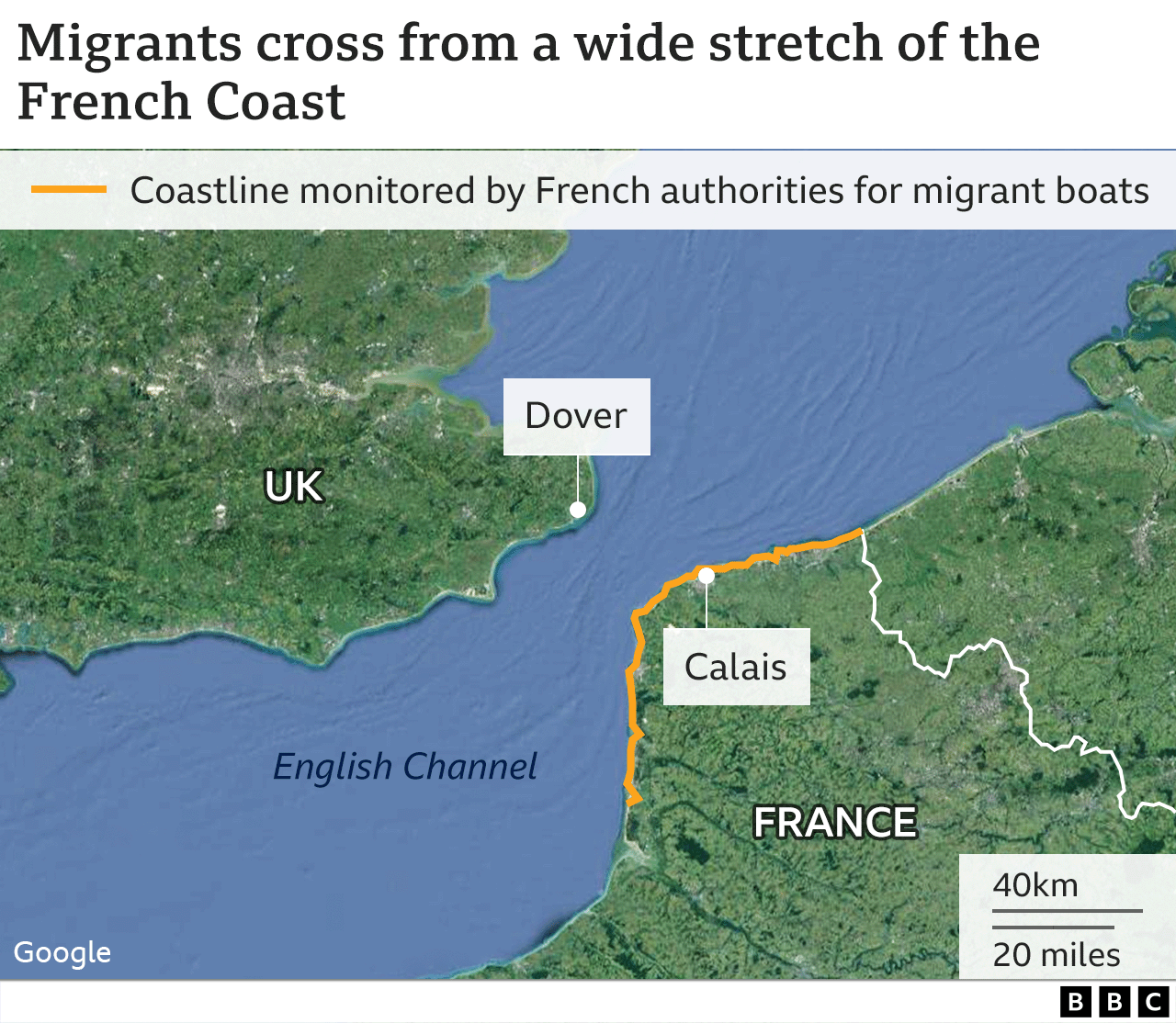

Born in landlocked Afghanistan, the 30-year-old looks out across the Channel waters. He watches the ships pass by the port of Calais.

But what should have been an exhilarating scene, his first time seeing an ocean, is crushed by fear.

Along with dozens of other Afghan men currently in Calais, Rahmat is waiting for a call from a smuggler, telling him it's time to cross.

"Looking out at the sea, it terrifies me. Like I'm staring death in the face," he says. "I wouldn't even be here if Afghanistan was safe."

According to the Home Office, the number of Afghans trying to cross the Channel to the UK has increased fivefold since the Taliban takeover. They now account for one in four people making the dangerous journey.

Within days of the Taliban takeover people from Rahmat's village started to disappear, their dead bodies later turning up without any explanation.

"We had no way of knowing what really happened to them or who did it."

In Kabul, the Taliban leadership announced a "general amnesty" for all government workers across the country and insisted they would be merciful towards those who opposed them.

However, in the last 12 months, several independent investigations by NGOs, external and media outlets, external have alleged the Taliban are behind hundreds of killings and forced disappearances of former government officials and members of the security forces.

Rahmat believes the murders in his village were revenge killings, carried out by members of the Taliban against particular individuals who worked for or supported the former government.

The local Taliban denied this, saying it was individuals with links to the so-called Islamic State group.

However, as Rahmat's father and two brothers were all former government workers, his family felt under threat. Fearing for his sons, Rahmat's father gave them all his blessing to leave Afghanistan.

After months of travelling through Iran, Turkey and Serbia, Rahmat finally arrived in Calais in June. There he met dozens of other Afghan men, many of them former government workers or security forces, and all trying to get to Britain.

Why the UK?

Standing on derelict ground on the edge of what was known as the Calais "Jungle", the refugee camp which was demolished in 2016, dozens of young Afghan men stand chatting whilst charging their phones.

Asked why they want to reach the UK, they replied: "Our cases will be heard there."

"Or at the very least", one man says, "we'll be given somewhere to shelter from the rain."

All of the men discuss the Dublin Regulation, an EU law which states an individual's asylum application should usually be processed by the first EU country they arrive in.

Many say their fingerprints were first taken in Bulgaria. But claim after being badly treated by the local border police they say they didn't want to stay. Instead they pushed on to the UK where the Dublin regulation does not apply.

The Bulgarian authorities declined to comment.

Serving in the army for just two and a half years, Sajid (R) says he has lost countless friends in the conflict

To cross the Channel, each of them has paid several thousand dollars to a network of smugglers to get them all the way from Afghanistan to Calais, and then on to the UK.

Sajid, 21, served in the Afghan army. He fought on the frontline against both the Taliban and Islamic State.

He now spends all his days and nights sleeping under a tree in Calais, less than 60 miles (96km) from the port of Dover.

He was on duty guarding a mountainous region close to the Pakistani border when he heard the news that the Taliban had taken the country.

"I was ready to fight on until the last bullet," he says.

But his superiors ordered him to "lay down our weapons and go home".

Fighting off the tears, he says he's lost track of the number of friends he lost in battle.

"I had to leave. The Taliban won't leave us alone. They say there is a general amnesty, but it's not true," says Sajid. "To this day, the retribution continues. Six people disappeared from my village. Many people have been killed."

News of the UK's controversial policy to send asylum seekers to Rwanda, an intended deterrent to those making dangerous journeys to the UK to claim asylum, has also reached the Afghans stuck in Calais.

Hashim, 23, who worked for the Afghan intelligence services, says he too lost colleagues within weeks of the Taliban takeover.

"Three of my colleagues went to meet in a park. The Taliban tracked them down and assassinated them on the spot. We were closer than brothers," he says.

"Crossing the water by boat, I know there is a 99.99% chance of dying. But if I'd stayed in Afghanistan, I'd already be dead.

"The UK may send us to Rwanda, but I want a chance to put my case before them and tell them why I fled my country."

- Published9 August 2022

- Published12 August 2022

- Published27 July 2022